“BANJO LESSONS?” A COLUMN ABOUT EC COMICS, PART 10

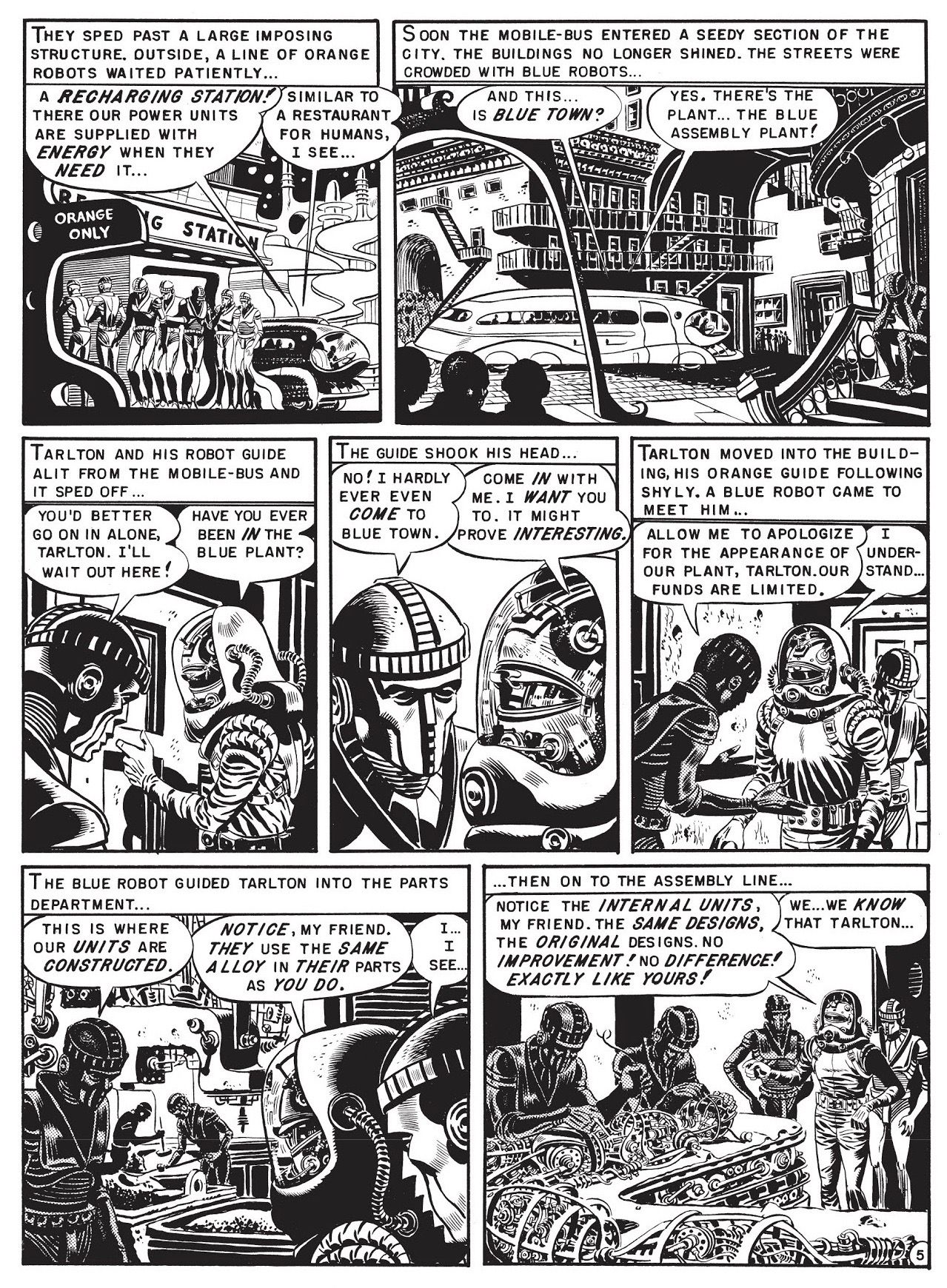

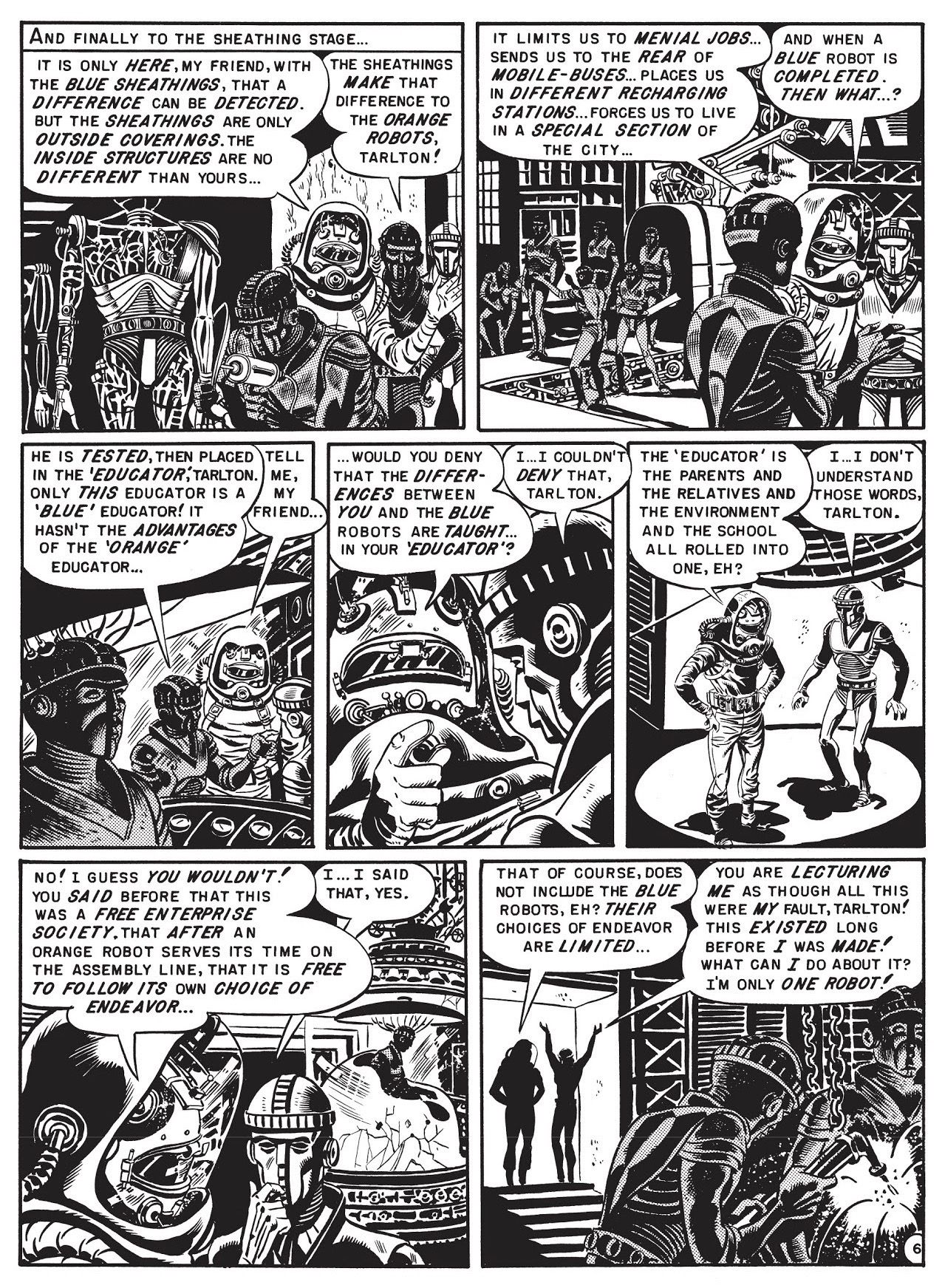

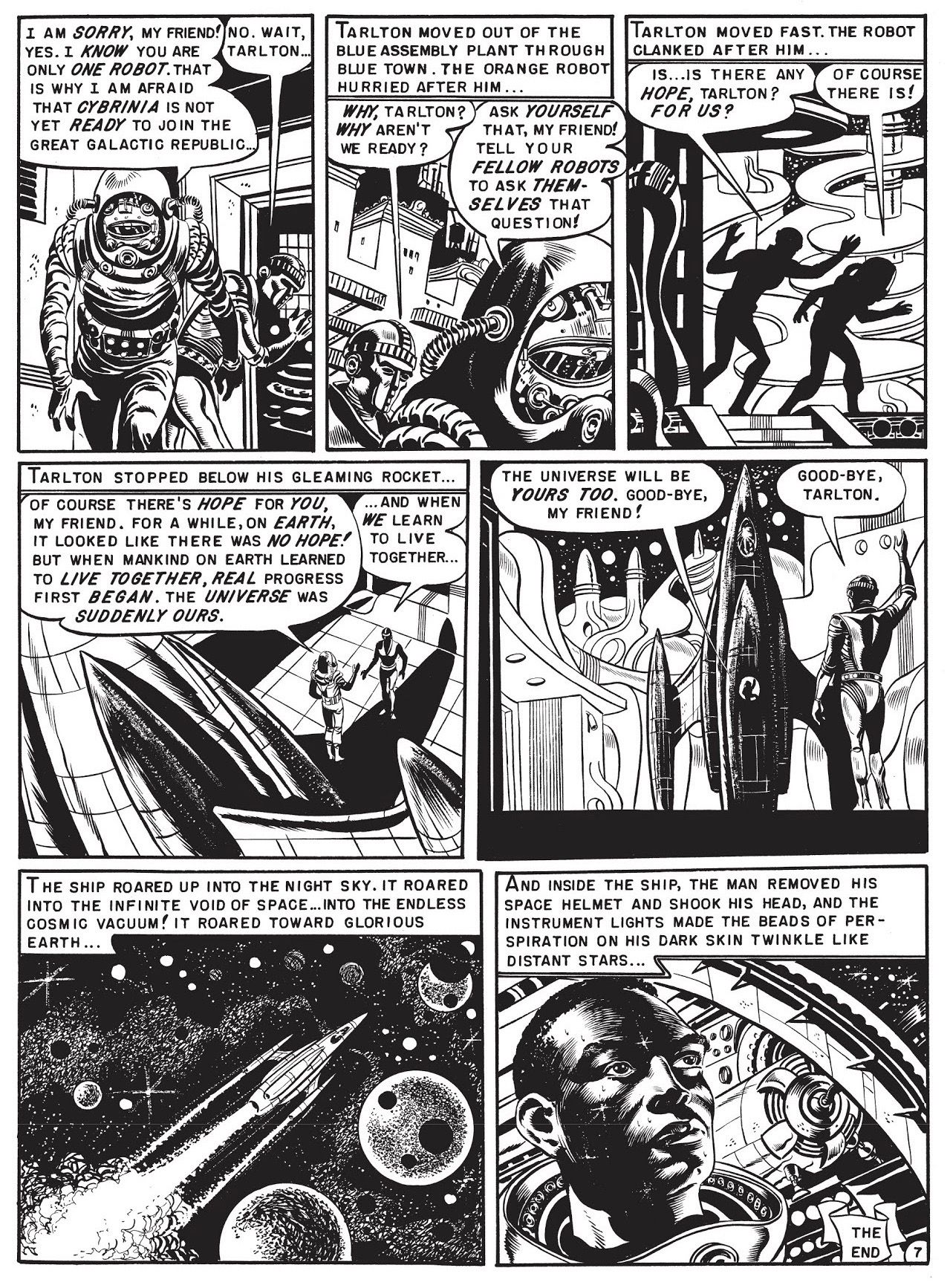

Let“s begin with a disclaimer and a friendly warning. While many comic books publishers put out horror tales and crime comics during the 1950s, there is a reason why the stories that were created during this period at EC Comics still connect with readers today and have done so over the years since The Comics Code Authority put a stop to what was EC“s most fruitful period by the end of 1954. Surely, most comic fans are able to name a handful of publishers that churned out some of the most gruesome tales once horror became the thing to do if you worked in the industry in the early 1950s. There were Atlas Comics and Harvey Comics and Fiction House and Avon, all of which had some impressive artistic talent working for them, and even a hero as patriotic as Captain America got into the horror game once superheroes fell out of favor with readers after the war. And though some of these old tales have seen a resurgence of sorts with their own reprints series dedicated to them, especially since many of the artists soon found career making opportunities when the superheroes staged their huge comeback in the early 60s, artists like Steve Ditko, Gene Colan and Don Heck, neither the stories nor their publishers had the impact that EC Comics had and still has. One of the reasons why this is the case has to do with the talent. Whereas any competitor of theirs had maybe one or two great artists working for them who mostly  did the lead-in story with the remaining pages handled by less experienced or less dedicated journeymen, EC Comics had assembled a most impressive bench of topnotch craftsmen by 1952. Some veterans of this still very young industry like Reed Crandall and Graham Ingels, others hungry up-and-comers like Al Williamson, Wally Wood or Frank Frazetta. On top of that, EC“s publisher and his editor and main writer Al Feldstein hired some of the most unusual illustrators whose idiosyncratic styles would go on to show generations of artists what was possible in sequential art once you took pencils and inks like a chainsaw to traditional storytelling. With ease and this early into their respective careers, cartoonists like Harvey Kurtzman and Bernard Krigstein showed an array of artistic choices that were dramatic and often poetic. Readers took note that these books from EC were special. The second aspect that was responsible for the impact and longevity EC Comics would ultimately have, were the narratives themselves. Not only were these tales highly reflective of the time in which they were created, most of them still hold up today as the saying goes. And herein lies the problem, because often good intentions turn out differently than intended or expected. It goes to the credit of men like Bill Gaines, Al Feldstein and Harvey Kurtzman (who worked as writer, artist and editor on EC Comics“ humor and war titles) that they were not content with putting out simplistic tales of good and evil but that they strived for something far more educational, and thus, by extension, more controversial. And this is where the disclaimer part comes in. While many of their wide-eyed, eight-year-old readers, boys and girls, ate up every new story with fervor, these tales about the cruel headmasters at gothic boarding schools who treated their young charges dismally, the older men who were two-timed by their much younger, desirable wives who they treated like a trophy, beasts from alien worlds that gorged on humans like we were cattle, the metamorphoses of bodies and minds, and the racist robots you encountered in the tale “Judgment Day”“, today, and even back then, as adults, we view these stories with different eyes. And perhaps we should and need to. However, what we see or what we think we see doesn“t remain constant. But it isn“t that these stories change. The words and the art remain unaltered, though newer reprint methods might adapt the color scheme. The players in these stories put on their show for us according to the script they know and in the only way they know. The readers, us, we go through many transformations with every new year. As we grow older and times change with us or time leaves us behind, we become less able to apply this wide-eyed stare we possess as youngsters, and we no longer want to. We expect that much from our adult selves. We task ourselves with looking deeper, hunting for the hidden meanings and by doing so, we not only deconstruct these two-dimensional characters who live in four-colored worlds in which they must perform their pathetic dance every time we check out any particular story, but ultimately we are going to discover something, an image or a word or a combination thereof, that solely seems to exist to offend us, or which we think must be offensive to others, for this is the nature of art that dares to raise its head into the wild and is about to leave the safe space of pure entertainment. But by its nature, art must be offensive. And we“re there to pass judgment if any of it still holds merit. What we will find hard to believe, though, and thus ignore in our assessment, these stories live in their own little bubble, and we the observer will not only bring our own perspective to them, but one that is very much shaped by time itself. “Judgment Day”“ is a very simple story. That it exists in the science fiction genre makes its message feel less imminent and personal, or so we think at first. Originally published in Weird Fantasy No. 18 (1953), this story by writer Al Feldstein and artist Joe Orlando take us on a tour to a faraway world which is inhabited by technically advanced, sentient robots. Tarlton, an astronaut from Earth, is sent to check up on Cybrinia, the planet of mechanical life, to learn if its population has developed “a society worthy of inclusion in Earth“s great galactic republic.”“ The man from Earth is greeted with much fanfare by Cybrinia“s citizens who“re most eager to show off their accomplishments, for him to deem the world they have built worthy of inclusion. And why shouldn“t they feel that their place is right next to Earth in this most prestigious organization? Was Earth not their own birthplace as Tarlton himself even now reiterates? He who is a “representative of [their] original creators”“: “Thousands of years ago, we placed a small handful of you upon this planet. This small handful was given the know-how to build more of you.”“ Thus, to convince Tarlton that indeed they have developed a perfect society during these millennia long past, the man in the bulky space suit is shown around by one of the orange robots. And lo, as his escort offers plenty of proof as he takes the emissary from Earth on a guided tour through one of Cybrinia“s major cities, these robots have evolved in the best possible way their designers could have hoped for. Indeed, the machine men have been able to create a vast array of technical wonderments, even machines to make more of themselves. However, there is a small problem. Among the original robots there were not only orange robots, but some were blue, identical in design to the orange ones, except for the color of their outside coverings. What about them? From his escort Tarlton learns that these robots live in what is referred to as “Blue Town”“. Surely, they can visit this place which is located on the south side of the city, but they better not ride in the car Tarlton“s guide had been provided with. There“s a mobile-bus going to that place, and on the off chance that some of the orange robots would need to use the public transport system, they conveniently have a section to themselves at the front of the bus. There is even a sign to remind you that you are supposed to sit in the back if you were one of the blue sheathed mechanical men. As for “Blue Town”“ itself, Tarlton quickly discovers that the nice, gleaming, modernistic buildings and the bright avenues have given way to dilapidated tenements and roads badly in want of repair. The factory where the blue robots are made is depressingly underfunded. Still new robots are built, all of which are identical to their orange brothers and sisters as they are all based on the same original design without any modification, only their design came with a blue casing originally. But apparently, on this world, this is what matters, as one of the blue automations explains to Tarlton: “The sheathings make that difference to the orange robots”¦ It limits us to menial jobs”¦ sends us to the rear of the mobile-buses”¦ places us in different recharching stations, forces us to live in a special section of the city”¦”“ And there is still more, as Tarlton learns that once the blue robots are assembled, the latest models are placed in an educator after testing, “only this educator is ”˜blue“ educator! It hasn“t the advantages of the ”˜orange“ educator”¦”“ It is by means of their educator that the blue robots learn about their place in this society. Though this is a free society, with the robots free to make their own choices once they“ve put in some hours at the assembly line, Tarlton concludes that the choices of the blue robots are severely limited. Ultimately, Tarlton“s judgment can only go one way, it must only go one way. Such a world that is not inclusive is not ready for inclusion in this republic.

did the lead-in story with the remaining pages handled by less experienced or less dedicated journeymen, EC Comics had assembled a most impressive bench of topnotch craftsmen by 1952. Some veterans of this still very young industry like Reed Crandall and Graham Ingels, others hungry up-and-comers like Al Williamson, Wally Wood or Frank Frazetta. On top of that, EC“s publisher and his editor and main writer Al Feldstein hired some of the most unusual illustrators whose idiosyncratic styles would go on to show generations of artists what was possible in sequential art once you took pencils and inks like a chainsaw to traditional storytelling. With ease and this early into their respective careers, cartoonists like Harvey Kurtzman and Bernard Krigstein showed an array of artistic choices that were dramatic and often poetic. Readers took note that these books from EC were special. The second aspect that was responsible for the impact and longevity EC Comics would ultimately have, were the narratives themselves. Not only were these tales highly reflective of the time in which they were created, most of them still hold up today as the saying goes. And herein lies the problem, because often good intentions turn out differently than intended or expected. It goes to the credit of men like Bill Gaines, Al Feldstein and Harvey Kurtzman (who worked as writer, artist and editor on EC Comics“ humor and war titles) that they were not content with putting out simplistic tales of good and evil but that they strived for something far more educational, and thus, by extension, more controversial. And this is where the disclaimer part comes in. While many of their wide-eyed, eight-year-old readers, boys and girls, ate up every new story with fervor, these tales about the cruel headmasters at gothic boarding schools who treated their young charges dismally, the older men who were two-timed by their much younger, desirable wives who they treated like a trophy, beasts from alien worlds that gorged on humans like we were cattle, the metamorphoses of bodies and minds, and the racist robots you encountered in the tale “Judgment Day”“, today, and even back then, as adults, we view these stories with different eyes. And perhaps we should and need to. However, what we see or what we think we see doesn“t remain constant. But it isn“t that these stories change. The words and the art remain unaltered, though newer reprint methods might adapt the color scheme. The players in these stories put on their show for us according to the script they know and in the only way they know. The readers, us, we go through many transformations with every new year. As we grow older and times change with us or time leaves us behind, we become less able to apply this wide-eyed stare we possess as youngsters, and we no longer want to. We expect that much from our adult selves. We task ourselves with looking deeper, hunting for the hidden meanings and by doing so, we not only deconstruct these two-dimensional characters who live in four-colored worlds in which they must perform their pathetic dance every time we check out any particular story, but ultimately we are going to discover something, an image or a word or a combination thereof, that solely seems to exist to offend us, or which we think must be offensive to others, for this is the nature of art that dares to raise its head into the wild and is about to leave the safe space of pure entertainment. But by its nature, art must be offensive. And we“re there to pass judgment if any of it still holds merit. What we will find hard to believe, though, and thus ignore in our assessment, these stories live in their own little bubble, and we the observer will not only bring our own perspective to them, but one that is very much shaped by time itself. “Judgment Day”“ is a very simple story. That it exists in the science fiction genre makes its message feel less imminent and personal, or so we think at first. Originally published in Weird Fantasy No. 18 (1953), this story by writer Al Feldstein and artist Joe Orlando take us on a tour to a faraway world which is inhabited by technically advanced, sentient robots. Tarlton, an astronaut from Earth, is sent to check up on Cybrinia, the planet of mechanical life, to learn if its population has developed “a society worthy of inclusion in Earth“s great galactic republic.”“ The man from Earth is greeted with much fanfare by Cybrinia“s citizens who“re most eager to show off their accomplishments, for him to deem the world they have built worthy of inclusion. And why shouldn“t they feel that their place is right next to Earth in this most prestigious organization? Was Earth not their own birthplace as Tarlton himself even now reiterates? He who is a “representative of [their] original creators”“: “Thousands of years ago, we placed a small handful of you upon this planet. This small handful was given the know-how to build more of you.”“ Thus, to convince Tarlton that indeed they have developed a perfect society during these millennia long past, the man in the bulky space suit is shown around by one of the orange robots. And lo, as his escort offers plenty of proof as he takes the emissary from Earth on a guided tour through one of Cybrinia“s major cities, these robots have evolved in the best possible way their designers could have hoped for. Indeed, the machine men have been able to create a vast array of technical wonderments, even machines to make more of themselves. However, there is a small problem. Among the original robots there were not only orange robots, but some were blue, identical in design to the orange ones, except for the color of their outside coverings. What about them? From his escort Tarlton learns that these robots live in what is referred to as “Blue Town”“. Surely, they can visit this place which is located on the south side of the city, but they better not ride in the car Tarlton“s guide had been provided with. There“s a mobile-bus going to that place, and on the off chance that some of the orange robots would need to use the public transport system, they conveniently have a section to themselves at the front of the bus. There is even a sign to remind you that you are supposed to sit in the back if you were one of the blue sheathed mechanical men. As for “Blue Town”“ itself, Tarlton quickly discovers that the nice, gleaming, modernistic buildings and the bright avenues have given way to dilapidated tenements and roads badly in want of repair. The factory where the blue robots are made is depressingly underfunded. Still new robots are built, all of which are identical to their orange brothers and sisters as they are all based on the same original design without any modification, only their design came with a blue casing originally. But apparently, on this world, this is what matters, as one of the blue automations explains to Tarlton: “The sheathings make that difference to the orange robots”¦ It limits us to menial jobs”¦ sends us to the rear of the mobile-buses”¦ places us in different recharching stations, forces us to live in a special section of the city”¦”“ And there is still more, as Tarlton learns that once the blue robots are assembled, the latest models are placed in an educator after testing, “only this educator is ”˜blue“ educator! It hasn“t the advantages of the ”˜orange“ educator”¦”“ It is by means of their educator that the blue robots learn about their place in this society. Though this is a free society, with the robots free to make their own choices once they“ve put in some hours at the assembly line, Tarlton concludes that the choices of the blue robots are severely limited. Ultimately, Tarlton“s judgment can only go one way, it must only go one way. Such a world that is not inclusive is not ready for inclusion in this republic.

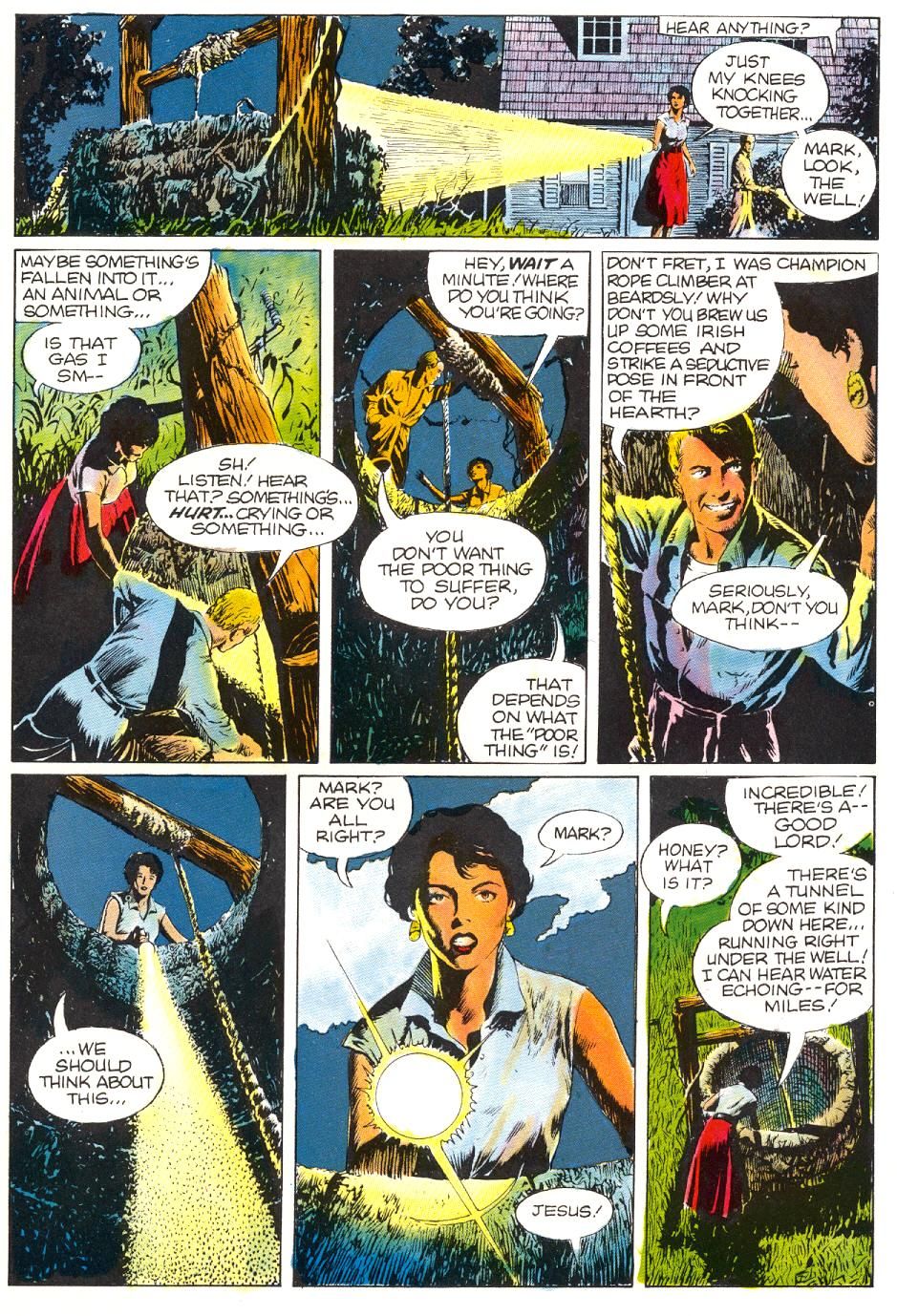

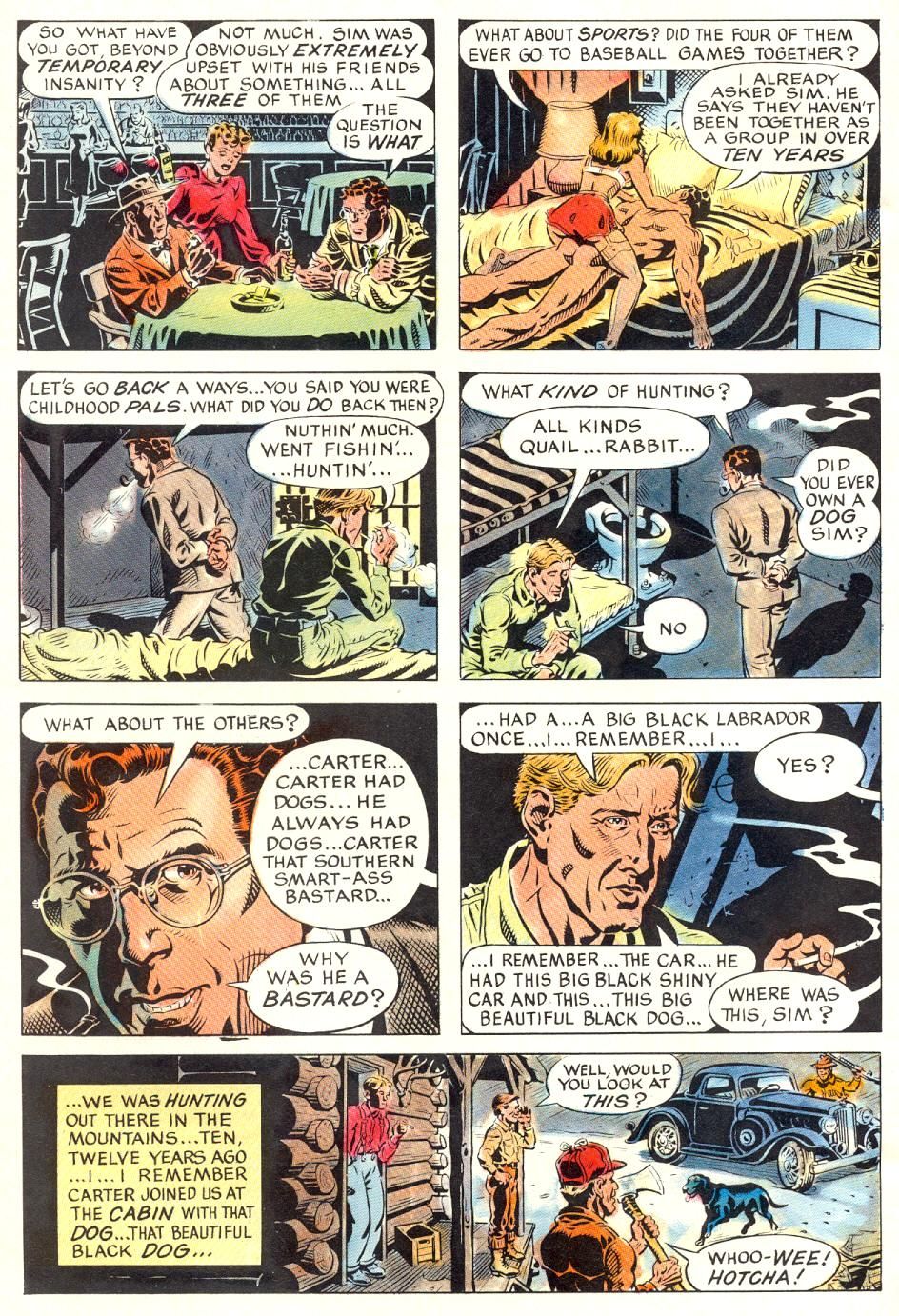

And this is where the aforementioned warning comes in, a double warning, actually. The first warning starts with a question. What are we to make of such a story? When viewed through the eyes of one of the children of the Atomic Age, what is presented as “science fiction”“ is very much a reality, sans robots, of course. But like in the story, in this child“s world, the bus stops are segregated, and so are the drinking fountains and the schools, and the neighborhoods and the restaurants. And from the two-dimensional, four-colored world Tarlton passes his judgment like an angry god, only that he is not angry, but sad. He had wished for a different verdict for Cybrinia and its modern, technologically evolved society. Alas, he also judges the world the child lives in. A child might identify with one of the orange robots, but it might also see its own face reflected on the gleaming sheathings of such a robot, and that mirror image to be glimpsed is one that belongs to a blue robot. What will this child, any child for that matter, make of this little sci-fi yarn that lacks any action or gore or blood? There are no knives at play here and no guns, no one is wielding an axe or another instrument to do some dismembering, there are no man-eating sharks that will feast on the wicked, or in the moralistic world of EC Comics, the gorgeous, two-timing wives and their not so secret lovers. It“s a boring tale, really. Still, this tale makes you feel less good about the world you live in, and as the child grows older it might get offended that without any warning the story is like a trap. You came for a science fiction yarn about cool looking robots on a fantastical world, robots doing some wild stuff like they usually did in other stories, but you are being preached to instead. There is this man who is send from Earth that tells you that no, if you do not accept machine men of all colors into your brave new world of shiny appliances, you  are not worthy for inclusion yourself. In fact, you“re the outcast. As an adult you might be either offended by how simplistic this parable depicts the highly complex, complicated subject of race relations, or you are offended that here is a character who is very much lecturing you. This is how Tarlton“s escort feels at least, who is not offended by what his society has wrought, but by Tarlton“s stance about it. The orange machine man thinks the man from Earth has wronged him, and thus he complains bitterly to the emissary who has become a juror and a judge: “You are lecturing me as though all this were my fault, Tarlton! This existed long before I was made!”“ He sees no fault in his own action, since as just one robot, he cannot change his world. Nor does he, as any adult deconstructing this story might very easily point out, actually have the ability to move much beyond his original programming or he would ask Tarlton why the original designers had given them this flaw from the beginning. Why had they seen it fit to create two versions of robots in the first place, one set orange, the other set identical, but simply colored blue? What were they to their creators who had long hence died? What sort of cruel joke had these mysterious overlords wanted to play on them? But this is where the first warning comes into play. This story, like most parables, does not hold up once it is brought too close to the light. The thin newsprint pages allow the light to pass through and they give up their secrets far too easily. If you look at these pages against the sunlight, you see what is on the other side of each page. And what is on the other side is an answer that comes too easily from these pages and from the concealed lips of the judge from Earth: “Of course there“s hope for you, my friend. For a while on Earth, it looked like there was no hope!… When mankind on Earth learned to live together, real progress first began. The universe was suddenly ours.”“ Tarlton is pleased that his new orange friend quickly gets the meaning of his words: “”¦ and when we learn to live together”¦”“, yes, Tarlton continues: “The universe will be yours, too.”“ But once you move beyond the initial shock of how easy, almost naïve this solution appears to be, what you are left with, is not a communiqué of hope that Tarlton delivers to his escort, a man whose whole existence is based around following the program of his gods and evolving from that original code. What Tarlton holds out to him as if dangling something shiny on a string, is a reward. The orange robots will find a way to integrate their world, not because they want to or because they believe this is the right thing to do, but because they want to hold this prize that Tarlton has promised to one of their kind. And this is why this story and the good intentions behind it ultimately fail once you become its author and you add your own skeptical point of view as the outside observer, as this god who made these robots in the first place. You play this kind of cruel game that you experience in the world around you. But yes, there is a twist, of course. Once back in his spaceship, Tarlton, the emissary from an Earth that is like our Earth but several millennia and many evolutionary steps removed, takes off his helmet, and the writer has this to say: “Inside his ship, the man removed his space helmet and shook his head, and the instrument lights made the beads of perspiration on his dark skin twinkle like distant stars.”“ It is of course a curious thing that the man who came to sit as juror and judge over the orange robots, the man to fault them for their way and their errors is a black man. Strange for the fact that this is the same man who has just told one of the ruling class on a foreign planet that if they created an inclusive society, they“re going to be rewarded for it: “At that time all of our scientific advances, our glory would become yours”¦”“ Again, once you begin to unravel the first strand and start to pull on this one loose thread just a bit more, what you are left with are a comic book publisher and his writer, both from Jewish heritage, padding each other on their backs for how progressive, almost subversive a tale they have created. You can have all the riches in the world, all the scientific advances if only you“d pretend play racial tolerance. But again, do not misunderstand their good intentions. These two men, Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein, for their own personal reason, were nihilists at worst and unrepentant cynics on their best days. To them, “Judgment Day”“ was a powerful story with the right kind of message, spun from their corporate offices on 225 Lafayette Street high above the streets of Manhattan and from their homes on Long Island. And to be fair, there is something daring at play here. By 1952, the two men were like a well-oiled machine. Gaines would provide Feldstein with springboards, one sentence synopses or even a loose plot, enough for Feldstein to spin an eight-page comic tale from. They did this across all the genres that were featured in EC“s lineup at that time, crime, horror and sci-fi, with the exception of just a handful of the crime and horror tales, those artist-writer Johnny Craig handled, and the humor and war books which were Harvey Kurtzman“s domain, though Feldstein would pitch in from time to time. The other exception being the two-dozen tales they adapted from the works of writer Ray Bradbury, initially sans an official permission from the genre author who was well on his way to become an American Classic. Once they“d been able to get an incredibly deep bench of artistic talent on board, publisher Bill Gaines and his editor-writers, Feldstein and Kurtzman, were on a roll. After he had been chasing trend after trend when he“d inherited the company from his late father, EC Comics had suddenly become the little company that could. It was the competition that was following them now. Once their gamble to bet the farm on horror comics had paid off, and with the addition of other titles and genres, which all sold reasonably well except for their science fiction books, Gaines simply could have kept feeding the machine with more stories in that vein, tales about the things that go bump in the night and crime tales about nice men who swindled old ladies out of their life“s savings or handsome drifters with designs on lonely housewives. But it was not in their nature. Gaines, who had been on the receiving end of his father“s leather belt a lot as an unhappy child had just divorced from a loveless and joyless marriage that his mother Jessie had arranged between her only son and his second cousin Hazel Grieb. Feldstein, who had two young daughters with his childhood sweetheart who he“d married when he was just eighteen years of age, took his Surfcaster as an excuse to get out of the house he“d bought near Jones Beach and Fire Island. When they worked on the crime stories that filled the pages of Crime SuspenStories, these were no longer stories about gangsters who planned a big heist like some three years ago when Al Feldstein had begun to work on books like Crime Patrol (which continued the numbering from a series Gaines“ father had started shortly before his death in a boating accident) and War Against Crime!, but stories about ordinary people, husbands and wives, and first and foremost, these were tales about the new American nightmare that was suburbia, at least in their minds. The underlying fabric of the idea of the Nuclear Family was slowly rotting away like the body of one of those unfortunate undead in one of their stories with art by Graham Ingels or Jack Davis, and Gaines and Feldstein took it upon themselves to explore scenes from marriages gone awry. It goes to their credit that they added a dose of darkly funny satire to the proceedings while they made use of the plots and story ideas from any James M. Cain and Jim Thompson novel, or Ray Bradbury short story for that matter, they could get their hands on. To most eight-year-old boys or girls who were more than ready to explore their neighborhoods, hidden by the cloak of invisibility you possess only as a child and only at that age when the adults hardly pay any attention to you at all, kids who on a subconscious level sensed what was going on in these dream houses, these stories must have felt like apples of knowledge, though they already had an inkling and here was confirmation. It is no coincidence that other than the much younger wives of old, wealthy fools and the aforementioned drifters, often the younger brothers of their hubbies or some low-level, lower class business associate, children figured large in these stories. These were smart kids who were often powerless, more so than kids usually are, and they were caught up in some frightful situation or weird mystery, something that occurred in their gardens, with no fault of their own and little means to do something about it, because none of the adults would listen to them or took note of their anxieties. But in the end, these kids made it out alive since they were in on a secret. Adult lives, especially the dealings of men and women and how they interacted towards each other, all of this must have been an exciting and terrifying to observe at that age and during those days, and with the filter of young eyes and an EC Comic right next to you. And sure enough, Gaines and Feldstein more than delivered on the promises they gave you with those thrilling covers and strange splash pages that often opened in medias res with an image of a strange occurrence which had happened so suddenly as if to put you completely off balance. These stories sucked you in, and even as a child you got that there was more going on than what any other horror or crime comic offered. These were tales for grown-ups.

are not worthy for inclusion yourself. In fact, you“re the outcast. As an adult you might be either offended by how simplistic this parable depicts the highly complex, complicated subject of race relations, or you are offended that here is a character who is very much lecturing you. This is how Tarlton“s escort feels at least, who is not offended by what his society has wrought, but by Tarlton“s stance about it. The orange machine man thinks the man from Earth has wronged him, and thus he complains bitterly to the emissary who has become a juror and a judge: “You are lecturing me as though all this were my fault, Tarlton! This existed long before I was made!”“ He sees no fault in his own action, since as just one robot, he cannot change his world. Nor does he, as any adult deconstructing this story might very easily point out, actually have the ability to move much beyond his original programming or he would ask Tarlton why the original designers had given them this flaw from the beginning. Why had they seen it fit to create two versions of robots in the first place, one set orange, the other set identical, but simply colored blue? What were they to their creators who had long hence died? What sort of cruel joke had these mysterious overlords wanted to play on them? But this is where the first warning comes into play. This story, like most parables, does not hold up once it is brought too close to the light. The thin newsprint pages allow the light to pass through and they give up their secrets far too easily. If you look at these pages against the sunlight, you see what is on the other side of each page. And what is on the other side is an answer that comes too easily from these pages and from the concealed lips of the judge from Earth: “Of course there“s hope for you, my friend. For a while on Earth, it looked like there was no hope!… When mankind on Earth learned to live together, real progress first began. The universe was suddenly ours.”“ Tarlton is pleased that his new orange friend quickly gets the meaning of his words: “”¦ and when we learn to live together”¦”“, yes, Tarlton continues: “The universe will be yours, too.”“ But once you move beyond the initial shock of how easy, almost naïve this solution appears to be, what you are left with, is not a communiqué of hope that Tarlton delivers to his escort, a man whose whole existence is based around following the program of his gods and evolving from that original code. What Tarlton holds out to him as if dangling something shiny on a string, is a reward. The orange robots will find a way to integrate their world, not because they want to or because they believe this is the right thing to do, but because they want to hold this prize that Tarlton has promised to one of their kind. And this is why this story and the good intentions behind it ultimately fail once you become its author and you add your own skeptical point of view as the outside observer, as this god who made these robots in the first place. You play this kind of cruel game that you experience in the world around you. But yes, there is a twist, of course. Once back in his spaceship, Tarlton, the emissary from an Earth that is like our Earth but several millennia and many evolutionary steps removed, takes off his helmet, and the writer has this to say: “Inside his ship, the man removed his space helmet and shook his head, and the instrument lights made the beads of perspiration on his dark skin twinkle like distant stars.”“ It is of course a curious thing that the man who came to sit as juror and judge over the orange robots, the man to fault them for their way and their errors is a black man. Strange for the fact that this is the same man who has just told one of the ruling class on a foreign planet that if they created an inclusive society, they“re going to be rewarded for it: “At that time all of our scientific advances, our glory would become yours”¦”“ Again, once you begin to unravel the first strand and start to pull on this one loose thread just a bit more, what you are left with are a comic book publisher and his writer, both from Jewish heritage, padding each other on their backs for how progressive, almost subversive a tale they have created. You can have all the riches in the world, all the scientific advances if only you“d pretend play racial tolerance. But again, do not misunderstand their good intentions. These two men, Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein, for their own personal reason, were nihilists at worst and unrepentant cynics on their best days. To them, “Judgment Day”“ was a powerful story with the right kind of message, spun from their corporate offices on 225 Lafayette Street high above the streets of Manhattan and from their homes on Long Island. And to be fair, there is something daring at play here. By 1952, the two men were like a well-oiled machine. Gaines would provide Feldstein with springboards, one sentence synopses or even a loose plot, enough for Feldstein to spin an eight-page comic tale from. They did this across all the genres that were featured in EC“s lineup at that time, crime, horror and sci-fi, with the exception of just a handful of the crime and horror tales, those artist-writer Johnny Craig handled, and the humor and war books which were Harvey Kurtzman“s domain, though Feldstein would pitch in from time to time. The other exception being the two-dozen tales they adapted from the works of writer Ray Bradbury, initially sans an official permission from the genre author who was well on his way to become an American Classic. Once they“d been able to get an incredibly deep bench of artistic talent on board, publisher Bill Gaines and his editor-writers, Feldstein and Kurtzman, were on a roll. After he had been chasing trend after trend when he“d inherited the company from his late father, EC Comics had suddenly become the little company that could. It was the competition that was following them now. Once their gamble to bet the farm on horror comics had paid off, and with the addition of other titles and genres, which all sold reasonably well except for their science fiction books, Gaines simply could have kept feeding the machine with more stories in that vein, tales about the things that go bump in the night and crime tales about nice men who swindled old ladies out of their life“s savings or handsome drifters with designs on lonely housewives. But it was not in their nature. Gaines, who had been on the receiving end of his father“s leather belt a lot as an unhappy child had just divorced from a loveless and joyless marriage that his mother Jessie had arranged between her only son and his second cousin Hazel Grieb. Feldstein, who had two young daughters with his childhood sweetheart who he“d married when he was just eighteen years of age, took his Surfcaster as an excuse to get out of the house he“d bought near Jones Beach and Fire Island. When they worked on the crime stories that filled the pages of Crime SuspenStories, these were no longer stories about gangsters who planned a big heist like some three years ago when Al Feldstein had begun to work on books like Crime Patrol (which continued the numbering from a series Gaines“ father had started shortly before his death in a boating accident) and War Against Crime!, but stories about ordinary people, husbands and wives, and first and foremost, these were tales about the new American nightmare that was suburbia, at least in their minds. The underlying fabric of the idea of the Nuclear Family was slowly rotting away like the body of one of those unfortunate undead in one of their stories with art by Graham Ingels or Jack Davis, and Gaines and Feldstein took it upon themselves to explore scenes from marriages gone awry. It goes to their credit that they added a dose of darkly funny satire to the proceedings while they made use of the plots and story ideas from any James M. Cain and Jim Thompson novel, or Ray Bradbury short story for that matter, they could get their hands on. To most eight-year-old boys or girls who were more than ready to explore their neighborhoods, hidden by the cloak of invisibility you possess only as a child and only at that age when the adults hardly pay any attention to you at all, kids who on a subconscious level sensed what was going on in these dream houses, these stories must have felt like apples of knowledge, though they already had an inkling and here was confirmation. It is no coincidence that other than the much younger wives of old, wealthy fools and the aforementioned drifters, often the younger brothers of their hubbies or some low-level, lower class business associate, children figured large in these stories. These were smart kids who were often powerless, more so than kids usually are, and they were caught up in some frightful situation or weird mystery, something that occurred in their gardens, with no fault of their own and little means to do something about it, because none of the adults would listen to them or took note of their anxieties. But in the end, these kids made it out alive since they were in on a secret. Adult lives, especially the dealings of men and women and how they interacted towards each other, all of this must have been an exciting and terrifying to observe at that age and during those days, and with the filter of young eyes and an EC Comic right next to you. And sure enough, Gaines and Feldstein more than delivered on the promises they gave you with those thrilling covers and strange splash pages that often opened in medias res with an image of a strange occurrence which had happened so suddenly as if to put you completely off balance. These stories sucked you in, and even as a child you got that there was more going on than what any other horror or crime comic offered. These were tales for grown-ups.

As subversive as these stories of those unfulfilled lives behind white picket fences and prim and proper front yards were in their own right, and such they were, Gaines, and by association Feldstein, were very restless with how they saw their world and society at large. To them, there were many ills that afflicted the American Way of Life during the early 1950s, and they were eager to address what they felt needed to be changed. More so, Gaines and Feldstein were willing to go to bat for what they believed in, though they also somewhat half-naively and half-foolishly believed that they had any say over what they could publish and who they could lecture about what. But by the mid-point of the decade they were no longer in a position comparable to that of Tarlton. Soon, their choices would become restricted. It isn“t without irony that “Judgment Day”“ and its troubled publication history would drive this point home to them. It was this story, that became the lightning rod for Gaines to tell that it was time to quit publishing comic books once and for all. EC published the issue with this story early in 1953. Only a few months later, the U.S. Senate established The United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency to investigate possible causes for an increase in violent crimes committed by teens and even children. Though chaired by Robert Hendrickson at its inception, a Republican from New Jersey, his Democratic colleague Senator Estes Kefauver from Tennessee soon took over. At the same time, letters began to reach the committee in which concerned groups of parents and representatives of church groups offered their two cents on who was responsible for the situation. Naturally those ten-cent comic books that were available to any youngster at every local drugstore and which offered some the most unspeakable tableaus of gore and dismemberment only a depraved mind  could come up with, namely what was shown in most horror or crime comics. Chief among those voices that were only too eager to offer up their opinion on this matter was a renowned child psychiatrist. Dr. Fredric Wertham had begun to point to what he perceived as an unmistakable connection between comics and the increase of violence in children and teens as early as 1948 when “The Saturday Review of Literature”“ had published his rather graphic article “The Comics”¦ Very Funny!”“ Even though not many people paid much attention to Dr. Wertham“s dramatically worded concerns, let alone parents who were busy with other things like getting a second car and paying down the mortgage on their dream home in the suburbs, Reader“s Digest soon called. The good doctor hastily penned a second piece which received a much wider circulation. He wasn“t the only person to find that articles on this subject were getting traction in the media. Moreover, Dr. Wertham had the credentials and the methodology to back up such claims, or so it would seem. That there was an investigative panel set up and by the United States Senate no less, lined up nicely with the book he was working on which was to offer much of his research into the harmful effects of comic book reading. When “Seduction of the Innocent”“ hit bookstores in April 1954, Senator Kefauver had already scheduled three days during which the subcommittee wanted to take a more in-depth look into comic books and the publishers that peddled such nasty wares vis-a-vis juvenile delinquency with the first two days taking place in April, just two days after Dr. Wertham“s book became available to parents and every other reader. This didn“t go unnoticed by the industry in question which became aware that now a target had been put on its back. At EC Comics, Bill Gaines quickly realized where this was heading, or perhaps, he simple overreacted. It is small wonder, though that he would. His once highly successful father, industry legend M.C. Gaines, who not only was one of the inventors of the medium itself but who also had co-founded All-American Comics, the home of such popular superheroes such as The Flash and Wonder Woman, had instilled in his son from an early age on that he would be a life-long failure. And not only with words, but with each and every beating he administered. This only drove young William to indulge and over-indulge, as if an increase in body mass offered more shelter against his father“s leather belt, yet this only provided the man his friends called Max, and who his employees and enemies addressed as Mr. Gaines, with a much larger area to hit. But react Bill Gaines did. In what was a completely unprecedented move, Bill and his editor Al Feldstein wrote an editorial to sound the alarm. This editorial, which covered a full page with small, neatly typed printing, began to run in every issue published by EC Comics around this time. While his mother Jessie Gaines had not heeded his cries for if not help, then support when he was just a child, the adult and still unhappy, still over-indulging younger Gaines was hoping that this time his calls would not go unanswered. But deep down in his heart he knew, he was hoping against hope, but still he tried: “Comics are under fire”¦ horror and crime comics in particular. Due to the efforts of ”˜do-gooders“ and ”˜do-gooder“ groups, a large segment of the public is being led to believe that certain comic magazines cause juvenile delinquency, warp the minds of America“s youth”¦”“ In the same editorial, Gaines and his editor Feldstein even went on the attack, and why wouldn“t they? Was there not a conspiracy underfoot to get them banned? “Among these ”˜do-gooders“ are: a psychiatrist who has made a lucrative career of attacking comic magazines”¦ publishing companies who do not publish comics and who would benefit by their demise”¦ groups of adults who would like to blame their lack of ability as responsible parents on comic mags instead of on themselves and various assorted headline hunters.”“ Gaines and Feldstein did not mince words either when it came to how they rated the impact these various factions had. They were dangerous: “These people are militant. They complain to local police officials, to local magazine retailers, to local wholesalers, and to their congressmen. They complain and complain and threaten and threaten. Eventually, everyone gets frightened. He removes books from display”¦ This wave of hysteria has seriously threatened the very existence of the whole comic magazine industry.”“ What seems highly dramatic, and perhaps it was, showed how astute Gaines was in his assessment of what was going on. Despite being a ruthless, violent man, Max Gaines knew how the game was played. The initial popularity of comics was in no small part caused by the attacks from local legislators on the racier pulp magazines in the mid-1930s. Publishers soon switched to the much cleaner thrills that the new funny books offered which were as cheaply if not cheaper to produce. To avert any unwanted attention from meddlers who might feel that these four-colored pamphlets were to the detriment of children“s healthy development, early on, comic publisher had established a board of advisors from various areas of education and with the right kind of resume to placate the media and to alleviate any fear an overly concerned parent may have towards letting their kids read comic books. As the older Gaines“ luck would have it, one of these experts in the medical profession and child education Max Gaines and his partner Jack Liebowitz hired for All-American Comics, had a pitch of his own. Psychologist William Moulton Marston suggested that perhaps an all-powerful superheroine was exactly the right kind of new character to join all these male demi-gods that had begun to populate the medium which had then only existed for a few years. Wonder Woman, who Marston created together with artist H.G. Peter, became an overnight smash hit once she was revealed to boys and girls and the whole world in 1942. When Gaines sold his stake in All-American in 1944 and he went on to found a new company he called Educational Comics, he quickly adopted this principle. Max invited six luminaries from the field of education onto his advisory board, three of which boasted a “Dr.”“ in front of their names, two were university professors. When Max had died in a boating accident in the summer of 1947, his business manager Sol Cohen soon disbanded the panel of experts. Now his son may have wished for these esteemed educators to present an insurmountable wall against attacks from outside the industry and from within, but alas, still he could refer to a few leadings lights in his editorial, three in total, each with a doctorate as well, who had come out in defense of the comic book industry. He and Feldstein even quoted Dr. David Abrahamsen, a criminologist as their own expert witness albeit by presenting a few statements from the esteemed man“s book “Who are the Guilty?”“ in the editorial: “Comic books do not lead to crime, although they have been widely blamed for it”¦ In my experience as a psychiatrist, I cannot remember having seen one boy or girl who has committed a crime, or who became neurotic or psychotic”¦ because he or she read comic books.”“ In closing, Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein pleaded with their young readers: “Wherever you can, let your voice and the voices of your parents be raised in protest over the campaign against comics. But first”¦ right now”¦ please write that letter to the Senate Subcommittee.”“ But with “Seduction of the Innocent”“ selected by the Book-of-the-Month-Club and being excerpted in “Ladies“ Home Journal”“, Gaines knew he needed to do more. Thus, he offered his testimony on the matter on the same day Dr. Fredric Wertham was to appear in front of the Subcommittee. In choosing this path and doing so while he was hopped-up on diet pills and caffeine, EC“s publisher poorly misjudged who his real enemy was. When he made light of Dr. Wertham during his opening statements, this only showed how ill prepared he was to grasp the whole situation. His real opponent was not Dr. Wertham, who knew how to present his questionable research into comic book violence and its influence on young, impressionable minds in the most sensationalistic manner. It were the statements Gaines made when he was questioned by the Senators, chief among them Senator Estes Kefauver that doomed him and well-nigh the whole industry. Estes Kefauver had become a star during the televised hearings on organized crime earlier in the ”˜50s. For a short time, he was even a contender for the highest job in the country, that of the President of the United States. Who was a man like Gaines to him? He was just another greedy and irresponsible peddler of smut, one of around twenty who put out around six hundred and fifty comic books on a monthly basis. However, Bill Gaines biggest enemy in that room on April 21, 1954 was Bill Gaines himself in that he attempted to defend the indefensible.

could come up with, namely what was shown in most horror or crime comics. Chief among those voices that were only too eager to offer up their opinion on this matter was a renowned child psychiatrist. Dr. Fredric Wertham had begun to point to what he perceived as an unmistakable connection between comics and the increase of violence in children and teens as early as 1948 when “The Saturday Review of Literature”“ had published his rather graphic article “The Comics”¦ Very Funny!”“ Even though not many people paid much attention to Dr. Wertham“s dramatically worded concerns, let alone parents who were busy with other things like getting a second car and paying down the mortgage on their dream home in the suburbs, Reader“s Digest soon called. The good doctor hastily penned a second piece which received a much wider circulation. He wasn“t the only person to find that articles on this subject were getting traction in the media. Moreover, Dr. Wertham had the credentials and the methodology to back up such claims, or so it would seem. That there was an investigative panel set up and by the United States Senate no less, lined up nicely with the book he was working on which was to offer much of his research into the harmful effects of comic book reading. When “Seduction of the Innocent”“ hit bookstores in April 1954, Senator Kefauver had already scheduled three days during which the subcommittee wanted to take a more in-depth look into comic books and the publishers that peddled such nasty wares vis-a-vis juvenile delinquency with the first two days taking place in April, just two days after Dr. Wertham“s book became available to parents and every other reader. This didn“t go unnoticed by the industry in question which became aware that now a target had been put on its back. At EC Comics, Bill Gaines quickly realized where this was heading, or perhaps, he simple overreacted. It is small wonder, though that he would. His once highly successful father, industry legend M.C. Gaines, who not only was one of the inventors of the medium itself but who also had co-founded All-American Comics, the home of such popular superheroes such as The Flash and Wonder Woman, had instilled in his son from an early age on that he would be a life-long failure. And not only with words, but with each and every beating he administered. This only drove young William to indulge and over-indulge, as if an increase in body mass offered more shelter against his father“s leather belt, yet this only provided the man his friends called Max, and who his employees and enemies addressed as Mr. Gaines, with a much larger area to hit. But react Bill Gaines did. In what was a completely unprecedented move, Bill and his editor Al Feldstein wrote an editorial to sound the alarm. This editorial, which covered a full page with small, neatly typed printing, began to run in every issue published by EC Comics around this time. While his mother Jessie Gaines had not heeded his cries for if not help, then support when he was just a child, the adult and still unhappy, still over-indulging younger Gaines was hoping that this time his calls would not go unanswered. But deep down in his heart he knew, he was hoping against hope, but still he tried: “Comics are under fire”¦ horror and crime comics in particular. Due to the efforts of ”˜do-gooders“ and ”˜do-gooder“ groups, a large segment of the public is being led to believe that certain comic magazines cause juvenile delinquency, warp the minds of America“s youth”¦”“ In the same editorial, Gaines and his editor Feldstein even went on the attack, and why wouldn“t they? Was there not a conspiracy underfoot to get them banned? “Among these ”˜do-gooders“ are: a psychiatrist who has made a lucrative career of attacking comic magazines”¦ publishing companies who do not publish comics and who would benefit by their demise”¦ groups of adults who would like to blame their lack of ability as responsible parents on comic mags instead of on themselves and various assorted headline hunters.”“ Gaines and Feldstein did not mince words either when it came to how they rated the impact these various factions had. They were dangerous: “These people are militant. They complain to local police officials, to local magazine retailers, to local wholesalers, and to their congressmen. They complain and complain and threaten and threaten. Eventually, everyone gets frightened. He removes books from display”¦ This wave of hysteria has seriously threatened the very existence of the whole comic magazine industry.”“ What seems highly dramatic, and perhaps it was, showed how astute Gaines was in his assessment of what was going on. Despite being a ruthless, violent man, Max Gaines knew how the game was played. The initial popularity of comics was in no small part caused by the attacks from local legislators on the racier pulp magazines in the mid-1930s. Publishers soon switched to the much cleaner thrills that the new funny books offered which were as cheaply if not cheaper to produce. To avert any unwanted attention from meddlers who might feel that these four-colored pamphlets were to the detriment of children“s healthy development, early on, comic publisher had established a board of advisors from various areas of education and with the right kind of resume to placate the media and to alleviate any fear an overly concerned parent may have towards letting their kids read comic books. As the older Gaines“ luck would have it, one of these experts in the medical profession and child education Max Gaines and his partner Jack Liebowitz hired for All-American Comics, had a pitch of his own. Psychologist William Moulton Marston suggested that perhaps an all-powerful superheroine was exactly the right kind of new character to join all these male demi-gods that had begun to populate the medium which had then only existed for a few years. Wonder Woman, who Marston created together with artist H.G. Peter, became an overnight smash hit once she was revealed to boys and girls and the whole world in 1942. When Gaines sold his stake in All-American in 1944 and he went on to found a new company he called Educational Comics, he quickly adopted this principle. Max invited six luminaries from the field of education onto his advisory board, three of which boasted a “Dr.”“ in front of their names, two were university professors. When Max had died in a boating accident in the summer of 1947, his business manager Sol Cohen soon disbanded the panel of experts. Now his son may have wished for these esteemed educators to present an insurmountable wall against attacks from outside the industry and from within, but alas, still he could refer to a few leadings lights in his editorial, three in total, each with a doctorate as well, who had come out in defense of the comic book industry. He and Feldstein even quoted Dr. David Abrahamsen, a criminologist as their own expert witness albeit by presenting a few statements from the esteemed man“s book “Who are the Guilty?”“ in the editorial: “Comic books do not lead to crime, although they have been widely blamed for it”¦ In my experience as a psychiatrist, I cannot remember having seen one boy or girl who has committed a crime, or who became neurotic or psychotic”¦ because he or she read comic books.”“ In closing, Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein pleaded with their young readers: “Wherever you can, let your voice and the voices of your parents be raised in protest over the campaign against comics. But first”¦ right now”¦ please write that letter to the Senate Subcommittee.”“ But with “Seduction of the Innocent”“ selected by the Book-of-the-Month-Club and being excerpted in “Ladies“ Home Journal”“, Gaines knew he needed to do more. Thus, he offered his testimony on the matter on the same day Dr. Fredric Wertham was to appear in front of the Subcommittee. In choosing this path and doing so while he was hopped-up on diet pills and caffeine, EC“s publisher poorly misjudged who his real enemy was. When he made light of Dr. Wertham during his opening statements, this only showed how ill prepared he was to grasp the whole situation. His real opponent was not Dr. Wertham, who knew how to present his questionable research into comic book violence and its influence on young, impressionable minds in the most sensationalistic manner. It were the statements Gaines made when he was questioned by the Senators, chief among them Senator Estes Kefauver that doomed him and well-nigh the whole industry. Estes Kefauver had become a star during the televised hearings on organized crime earlier in the ”˜50s. For a short time, he was even a contender for the highest job in the country, that of the President of the United States. Who was a man like Gaines to him? He was just another greedy and irresponsible peddler of smut, one of around twenty who put out around six hundred and fifty comic books on a monthly basis. However, Bill Gaines biggest enemy in that room on April 21, 1954 was Bill Gaines himself in that he attempted to defend the indefensible.

The second warning: don“t let other people tell you what you can see and what not, especially when it comes to art. Words and pictures are magic in that they hold a special power. People who crave power themselves know this. Once he had been established in his position of power and holding court over all things comic books, the man nicknamed “The Comics Czar”“, Judge Charles Murphy, made sure, that no political statements could be made in these four-color pamphlets aimed at children. After Gaines“ well-intended, but mostly poorly worded testimony had forced the industry to act quickly, he was very much at the mercy of a group of comic book publishers led by DC Comics and Archie Comics, who established a self-regulatory body, the Comics Magazine Association of America, the same publishers he“d alluded to in his editorial. While a prior attempt to form any such organization and to set forth a set of guidelines to govern the content of comic books had failed, ironically EC Comics had been a founding member but had quickly terminated their participation, whereas publisher Dell had refused to join right away, now it was a matter of survival for some of the smaller publishers such as Gaines“ own outfit. Though Batman and Superman had been named in Dr. Wertham“s book, DC Comics and especially Archie Comics were a clean enough act, but they also knew that EC and their ilk was hurting their bottom line. Knowing full well that with the new rules that would be set forth in the Comic Code Authority they would take much of the bite out of their much more lurid competitors, they lobbied these new guidelines into effect and pushed for a non-nonsense figure of authority, a man who was beyond reproach and  thus would serve as the CMAA“s spokesperson to the public. Judge Murphy, Mr. Comics Code Authority, soon became a nemesis for Gaines and company. Forced to abandon their horror and crime comics by the end of 1954, the bulk of books that made up their vastly successful New Trend Line, Gaines announced a publishing initiative that was designed to fit to the changed times. The so-called New Direction titles were for the most part a bland affair, hardly distinguishable from the wares of their competitors save for the quality of the artwork, but all of these books now carried the Code“s seal of approval which ensure that at least they“d get distribution. The only remnant from their prior offerings was a re-branded and much cleaner Weird Science Fantasy (low sales had made them merge their sci-fi books into just one title). Now with its new name Incredible Science Fiction, most of the creativity and thought-provoking ideas which had garnered Weird Science and Weird Fantasy a small, but very loyal readership, had to be left behind. Bill tried anyway and when a year later he submitted issue No. 33 to the CCA to obtain approval from Judge Murphy, the issue was promptly rejected. The issue included a story drawn by Angelo Torres. “An Eye for an Eye was imaginative, beautifully drawn and poetic, but Murphy flat-out refused to allow it. He“d demanded many changes prior to this from Gaines and company during the preceding months, but in this case, he didn“t even suggest any changes that could be made. Gaines had no choice but to withdraw the story. The story would first appear in 1971 when it was among the twenty-three stories selected by Robert Marion Stewart, a comic fan turned comic book writer and publisher, and Bill Gaines for The EC Horror Library, a one-shot hardcover published by Nostalgia Press. All of the other tales were reprints and all came from EC“s New Trend books i.e. books prior to the establishment of the Comics Code, with one exception. “Master Race”“, a tale by Gaines, Feldstein and illustrator Bernie Krigstein that dealt with the Holocaust, had miraculously found inclusion in Impact No. 1 (1955). Ostensible promoted as one of the New Direction titles, the first issue had been put out sans the Code“s seal prominently shown on its cover. Strapped for time, since he had a deadline to meet with his printer, Gaines submitted “Judgment Day”“ as the replacement for “An Eye for an Eye”“ as the fourth story to be featured in Incredible Science Fiction. This time around, Judge Murphy at least pointed out a few things he wanted changed. “I went in there with the story and Murphy says, ”˜It can“t be a Black man“”¦”“, Al Feldstein later recalled. Feldstein tried to explain “that“s the whole point of the story!”“, but the Comics Czar wouldn“t budge. Once Gaines learned of this development, he got on the phone with the judge. “I“m going to call a press conference on this. You have no grounds, no basis on this. I“ll sue you”“, he bellowed into the receiver. Murphy was willing to make a concession, but once again not without some reservations. “Well, you gotta take the perspiration off”“, he said according to Feldstein when Al was interviewed in 2000 for “Tales of Terror: The EC Companion”“ by authors Fred Von Bernewitz and Grant Geissman. Feldstein continued with his recollections: “I had the stars glistening in the perspiration on his Black skin. Bill said ”˜Fuck you“ and he hung up.”“ With his final FU to the Comic Czar, spoken with much exasperation and frustration, Bill made the decision to get out of comic. He briefly tried his luck with a line of magazines which re-told some of the earlier stories in prose with new illustrations done by some of the finest EC artists, not the original artists who had worked on the stories when they were published originally, but with the artists switched around. The Picto-Fiction line lasted only a handful of issues and some of the art commissioned for later issues, like a re-imagining of Feldstein and Wally Wood“s masterpiece “Came the Dawn”“, with new art by wunderkind Frank Frazetta, today only exists in fragments. Gaines, after he“d finally found something he was good at, despite the judgment his father had instilled in him as a boy, finally called it quits as far as comic books were concerned. He still had MAD Magazine to fall back on, though, and it was a smash hit. The fact that MAD“s initial editor, Harvey Kurtzman had made the suggestion to convert MAD from a comic book into a magazine even before the Comics Code, kept it out of the hands of Judge Murphy.

thus would serve as the CMAA“s spokesperson to the public. Judge Murphy, Mr. Comics Code Authority, soon became a nemesis for Gaines and company. Forced to abandon their horror and crime comics by the end of 1954, the bulk of books that made up their vastly successful New Trend Line, Gaines announced a publishing initiative that was designed to fit to the changed times. The so-called New Direction titles were for the most part a bland affair, hardly distinguishable from the wares of their competitors save for the quality of the artwork, but all of these books now carried the Code“s seal of approval which ensure that at least they“d get distribution. The only remnant from their prior offerings was a re-branded and much cleaner Weird Science Fantasy (low sales had made them merge their sci-fi books into just one title). Now with its new name Incredible Science Fiction, most of the creativity and thought-provoking ideas which had garnered Weird Science and Weird Fantasy a small, but very loyal readership, had to be left behind. Bill tried anyway and when a year later he submitted issue No. 33 to the CCA to obtain approval from Judge Murphy, the issue was promptly rejected. The issue included a story drawn by Angelo Torres. “An Eye for an Eye was imaginative, beautifully drawn and poetic, but Murphy flat-out refused to allow it. He“d demanded many changes prior to this from Gaines and company during the preceding months, but in this case, he didn“t even suggest any changes that could be made. Gaines had no choice but to withdraw the story. The story would first appear in 1971 when it was among the twenty-three stories selected by Robert Marion Stewart, a comic fan turned comic book writer and publisher, and Bill Gaines for The EC Horror Library, a one-shot hardcover published by Nostalgia Press. All of the other tales were reprints and all came from EC“s New Trend books i.e. books prior to the establishment of the Comics Code, with one exception. “Master Race”“, a tale by Gaines, Feldstein and illustrator Bernie Krigstein that dealt with the Holocaust, had miraculously found inclusion in Impact No. 1 (1955). Ostensible promoted as one of the New Direction titles, the first issue had been put out sans the Code“s seal prominently shown on its cover. Strapped for time, since he had a deadline to meet with his printer, Gaines submitted “Judgment Day”“ as the replacement for “An Eye for an Eye”“ as the fourth story to be featured in Incredible Science Fiction. This time around, Judge Murphy at least pointed out a few things he wanted changed. “I went in there with the story and Murphy says, ”˜It can“t be a Black man“”¦”“, Al Feldstein later recalled. Feldstein tried to explain “that“s the whole point of the story!”“, but the Comics Czar wouldn“t budge. Once Gaines learned of this development, he got on the phone with the judge. “I“m going to call a press conference on this. You have no grounds, no basis on this. I“ll sue you”“, he bellowed into the receiver. Murphy was willing to make a concession, but once again not without some reservations. “Well, you gotta take the perspiration off”“, he said according to Feldstein when Al was interviewed in 2000 for “Tales of Terror: The EC Companion”“ by authors Fred Von Bernewitz and Grant Geissman. Feldstein continued with his recollections: “I had the stars glistening in the perspiration on his Black skin. Bill said ”˜Fuck you“ and he hung up.”“ With his final FU to the Comic Czar, spoken with much exasperation and frustration, Bill made the decision to get out of comic. He briefly tried his luck with a line of magazines which re-told some of the earlier stories in prose with new illustrations done by some of the finest EC artists, not the original artists who had worked on the stories when they were published originally, but with the artists switched around. The Picto-Fiction line lasted only a handful of issues and some of the art commissioned for later issues, like a re-imagining of Feldstein and Wally Wood“s masterpiece “Came the Dawn”“, with new art by wunderkind Frank Frazetta, today only exists in fragments. Gaines, after he“d finally found something he was good at, despite the judgment his father had instilled in him as a boy, finally called it quits as far as comic books were concerned. He still had MAD Magazine to fall back on, though, and it was a smash hit. The fact that MAD“s initial editor, Harvey Kurtzman had made the suggestion to convert MAD from a comic book into a magazine even before the Comics Code, kept it out of the hands of Judge Murphy.

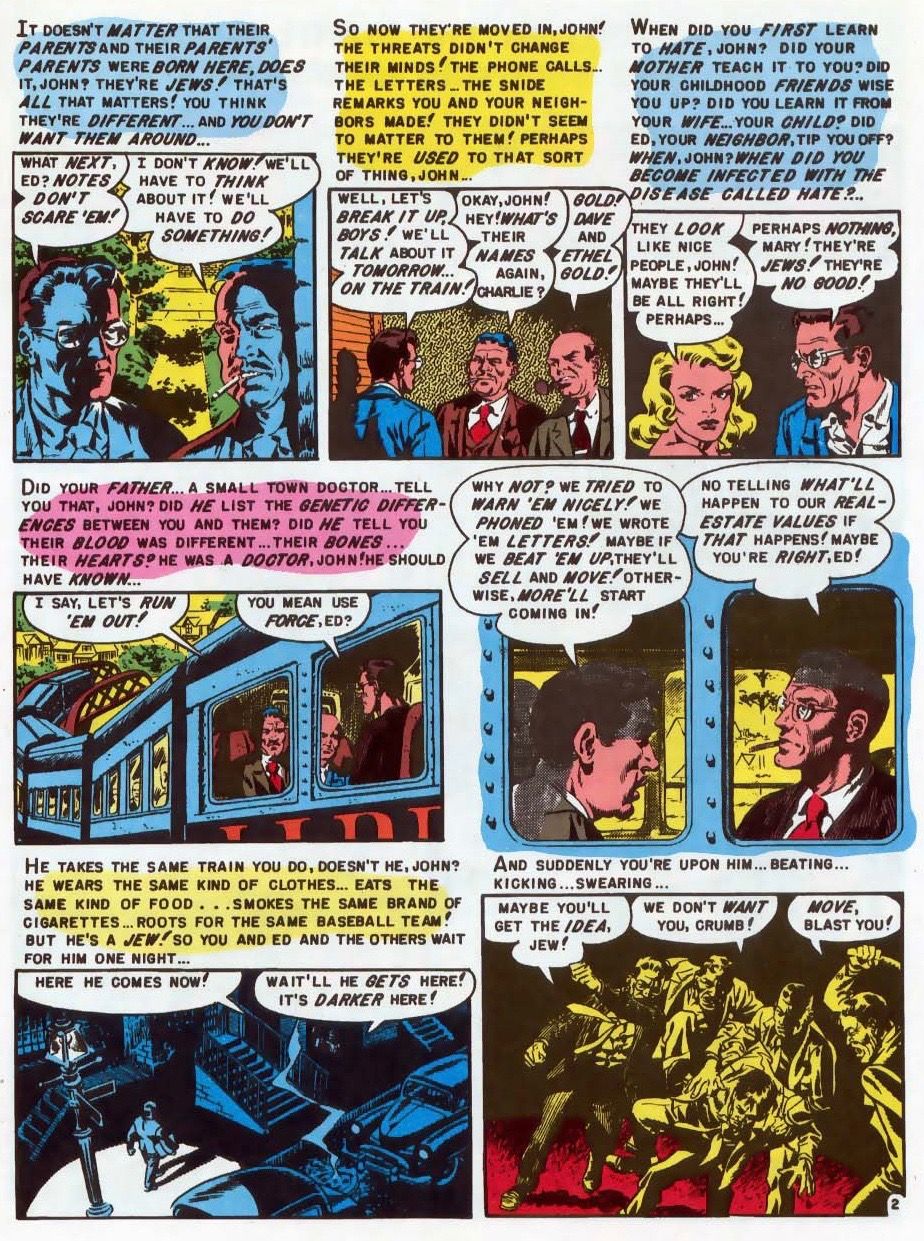

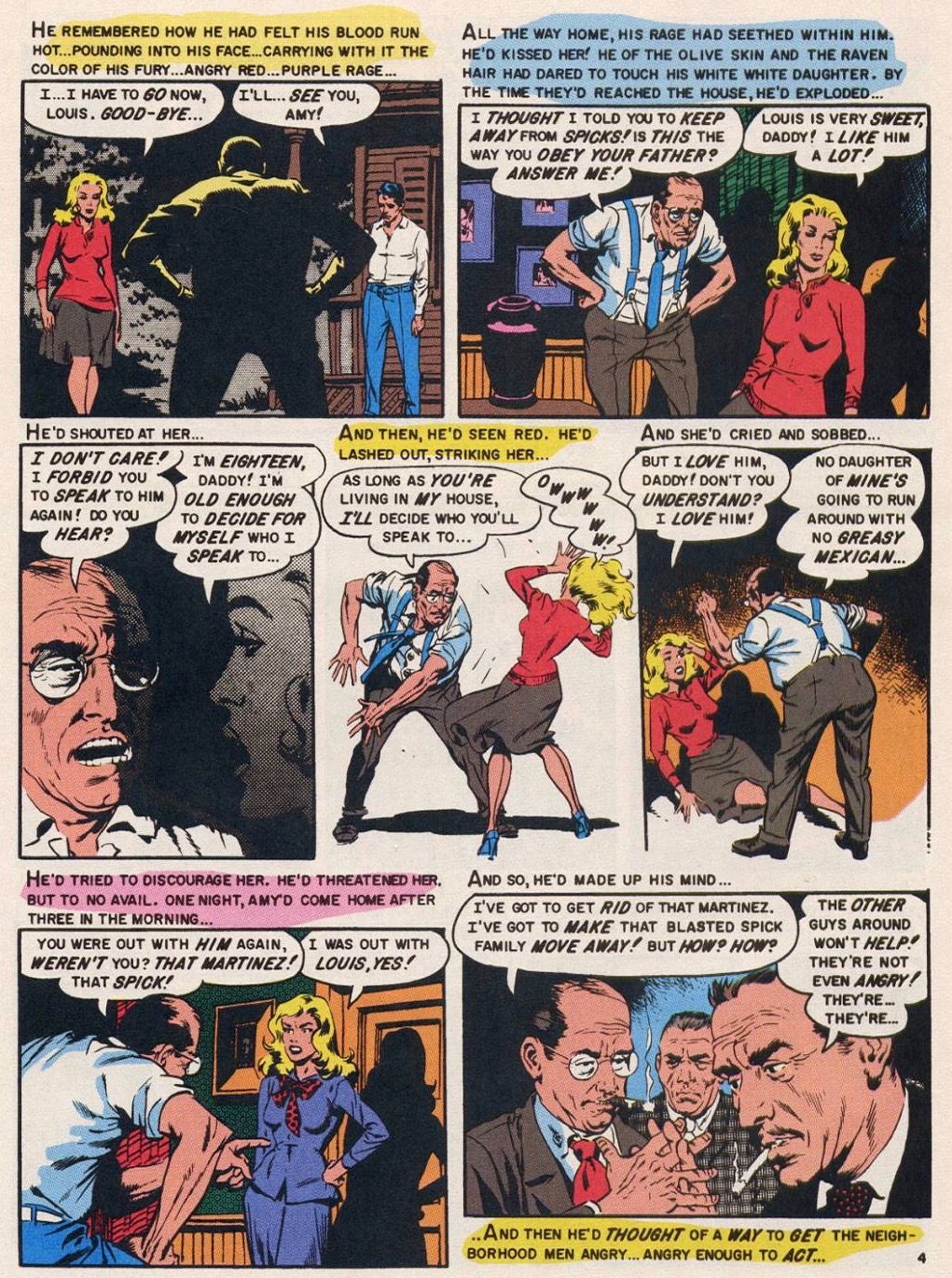

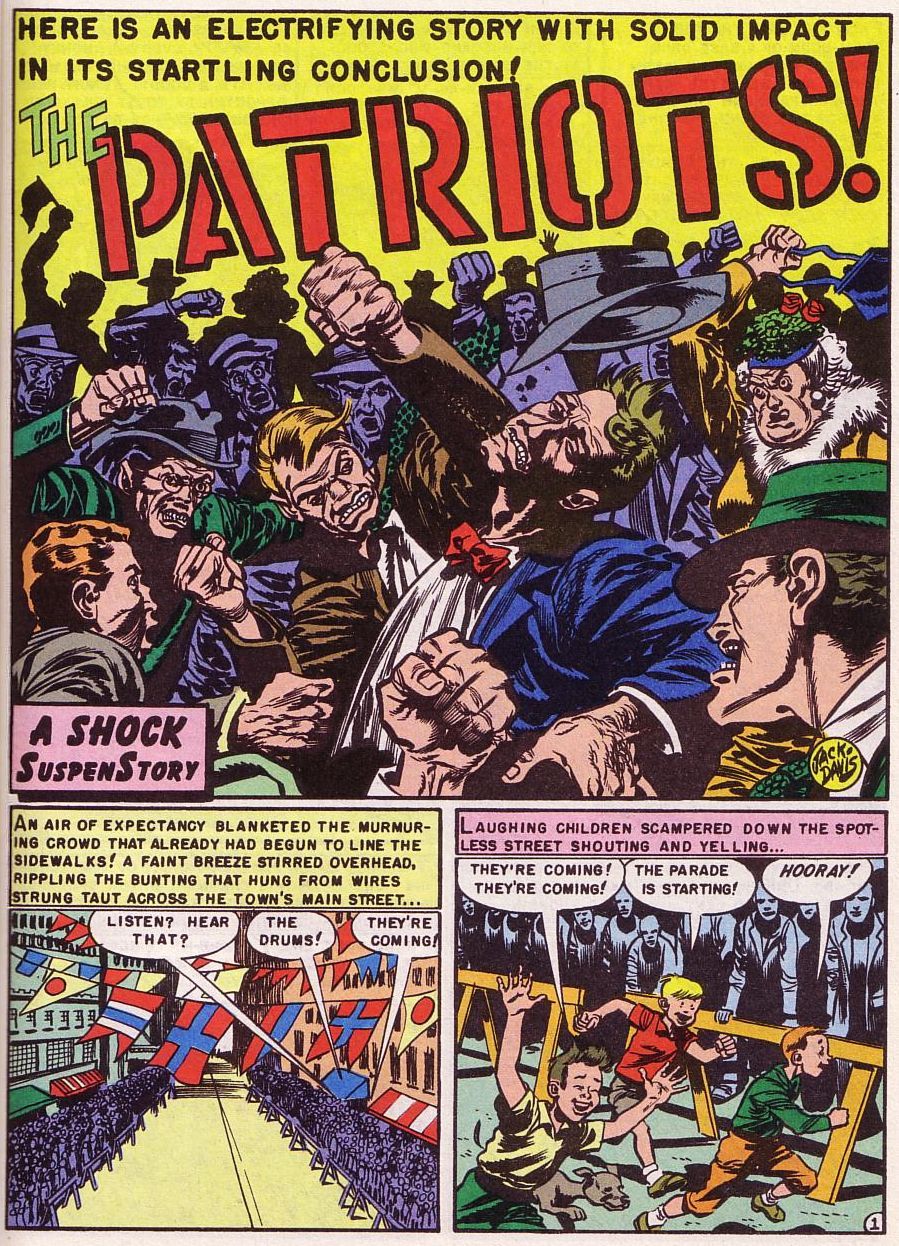

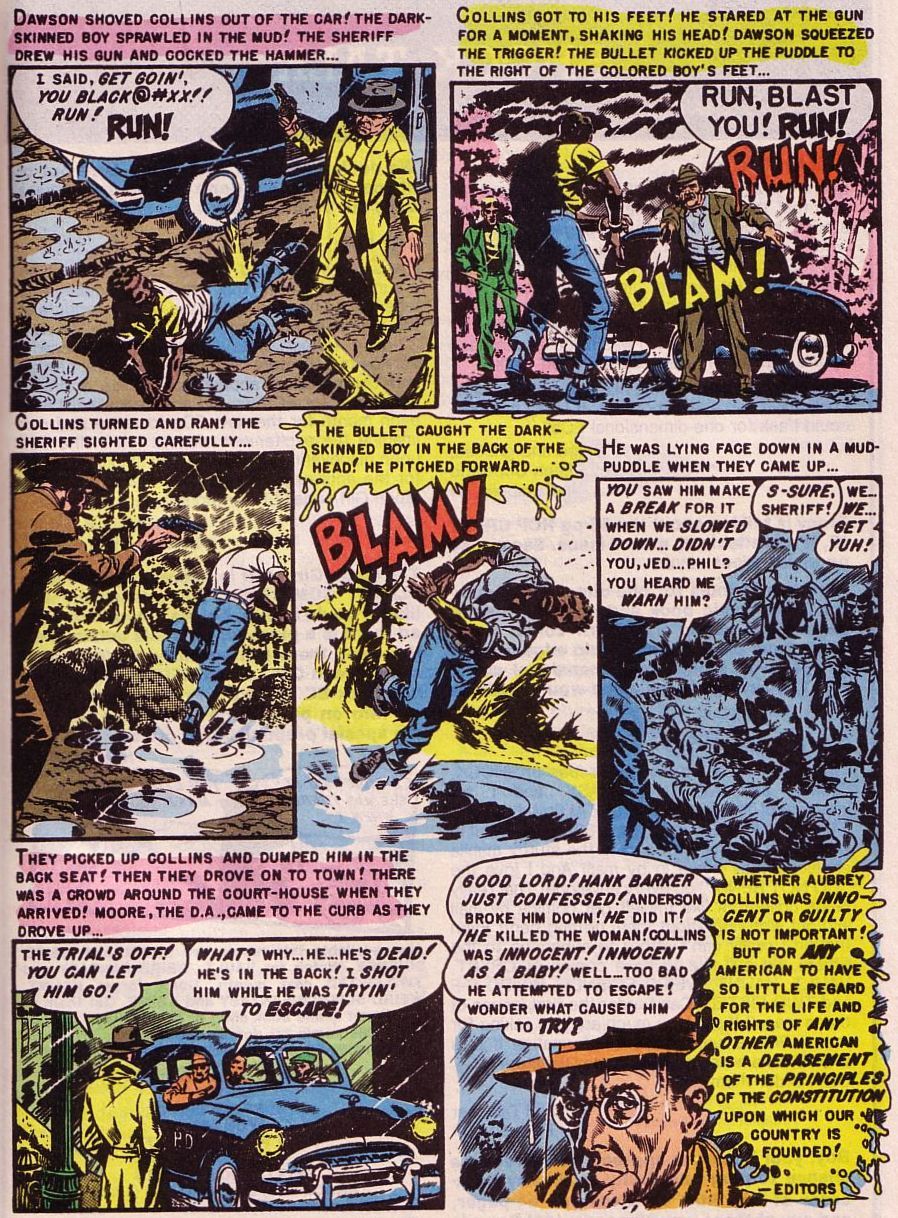

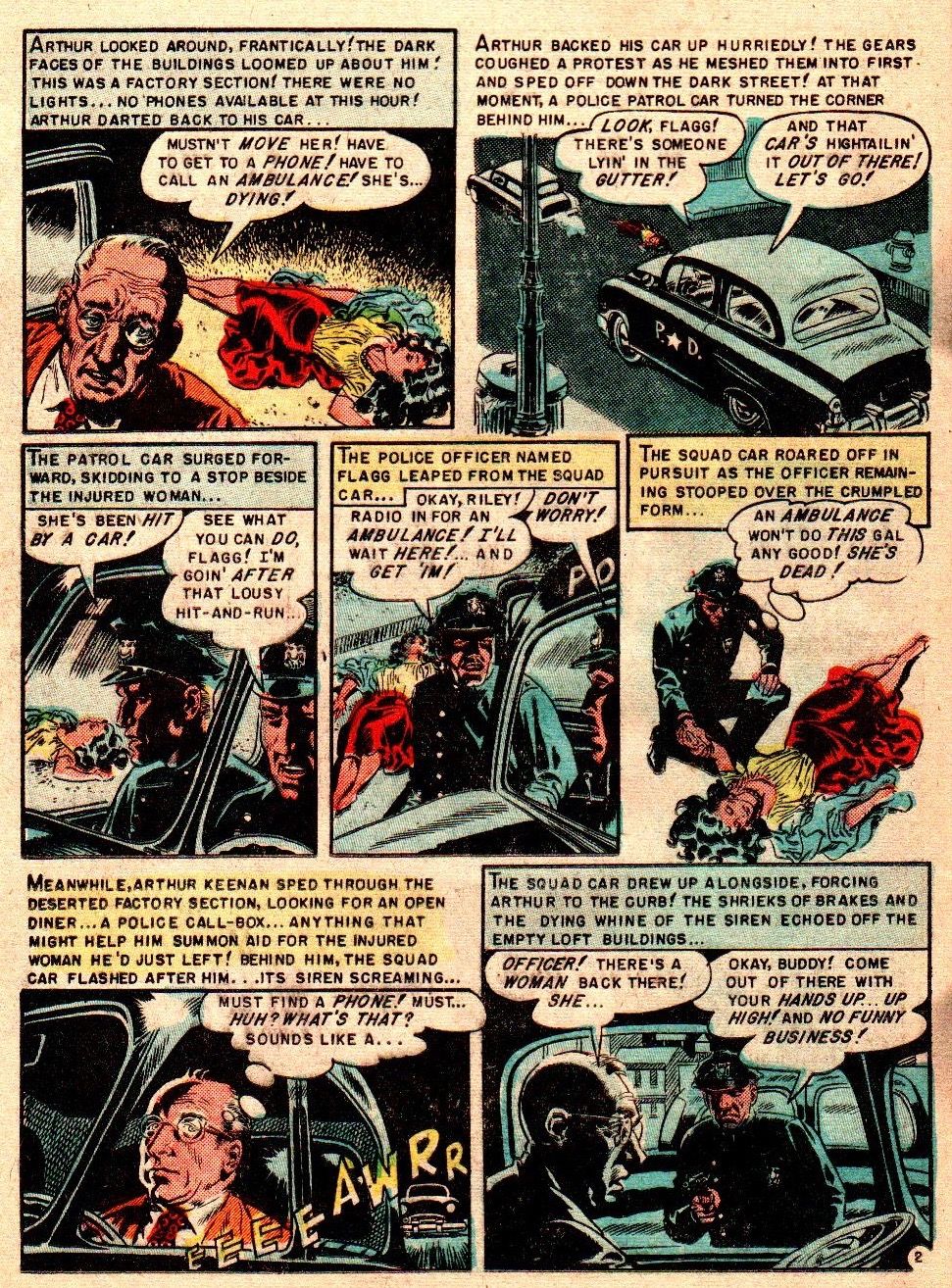

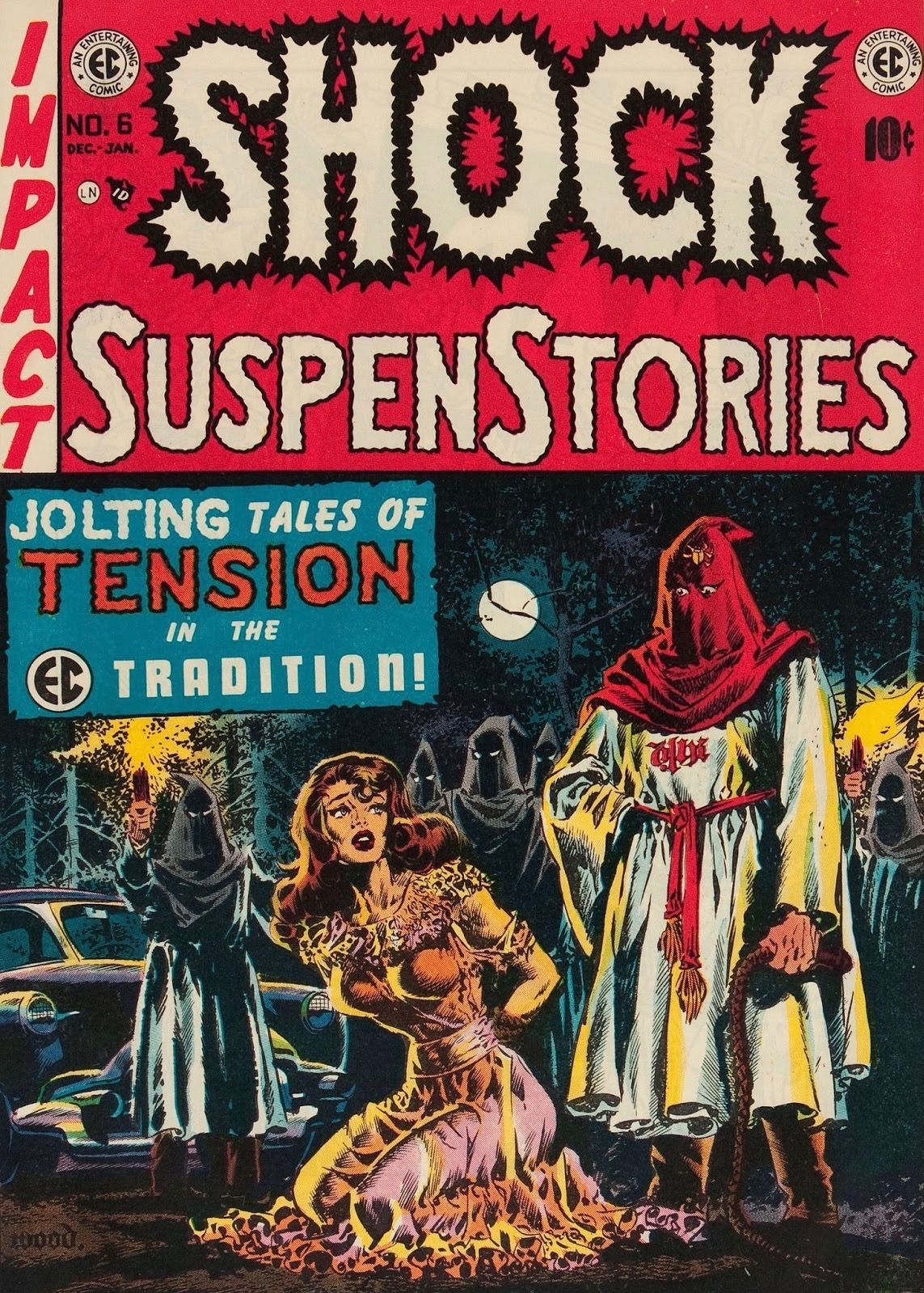

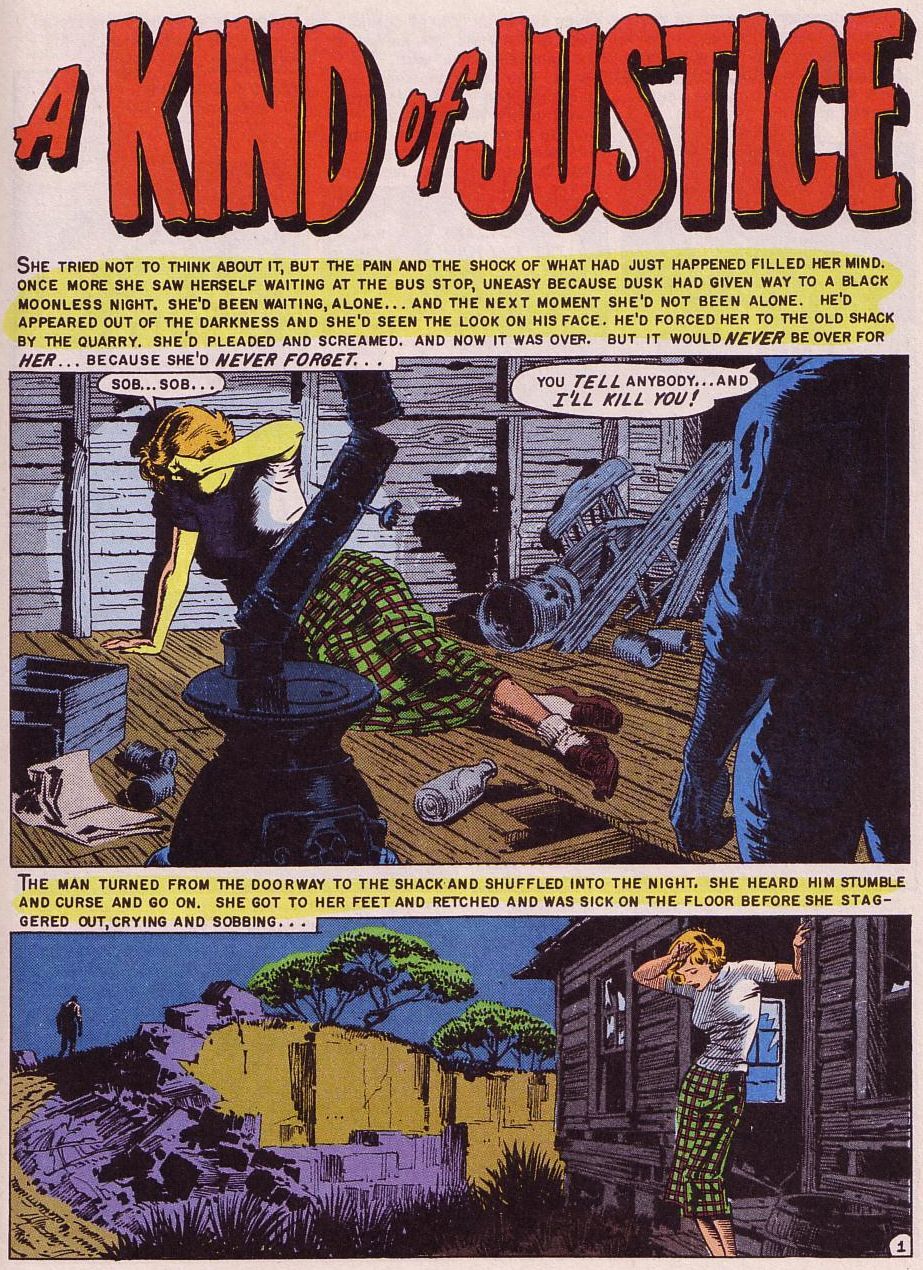

There is a certain irony in the fact that when Bill Gaines“ father had founded the company, EC stood for Educational Comics. This was when M.C. Gaines, the man who had been one of the inventors of comics, if not the inventor, and who was known for his good business sense and great timing, had believed that comics named Picture Stories from the Bible and Picture Stories from American History would turn out to be a success in a market place that in 1944 was still being dominated by extremely confident, highly patriotic, colorfully garbed men in capes and tights and girls who often wore considerably less clothing, but who were equally masked. Although he was many things, and many things all at once, Max Gaines, most certainly was no fool. Once Max Gaines and his business manager Sol Cohen discovered that these books, in fact the whole line of titles M.C. had created with good intentions or because he believed that such books would soon become the next hot thing, or perhaps with a mixture of both, were not selling enough units initially, he and Cohen soon created a completely different line of books, only these would be sold under a banner that read Entertaining Comics. Soon, crooks and police officers battled it out in titles such as International Comics, soon renamed International Crime Comics, while the covers showed impossible glamorous ladies in perilous situations and as silent observers, while two alpha males fought each other for dominance. Still, even as the first issue of International Comics hit the newsstands in the Spring of 1947, M.C. and Cohen were preparing more exciting wares for their main line, hoping Picture Stories from World History and Picture Stories from Shakespeare would find their intended audience at some point. While indeed Gaines tried to educate young readers, the books didn“t offer much else. Max did not intend for there to be any discourse  when books on American History had parts with titles such as “Period of Colonization”“ and “Founding of our Nation”“. Nor did Max plan to educate any youngsters with his Entertaining line. Though these books would depict women as capable, despite the tantalizing way in which they got portrayed by the artists on the covers and in the stories themselves, a few of the ideas put forth by William Moulton Marston hadn“t gone by unnoticed and neither had the early success he“d had with Wonder Woman back at All-American Comics, these were escapist fantasies. His son Bill though, did something rather remarkable. Sometime in 1952, he began to use what by then was a comic book line which exclusively used the name Entertaining Comics, as a platform to advance social causes he felt strongly about. So much so that he voiced strong objection to Dr. Wertham“s misrepresentations of what his and Al Feldstein“s real motives were. During his testimony, the psychiatrist had pointed out the number of times they“d used racist epithets in one story. Once Gaines got on the witness stand right after the psychiatrist had offered his testimony, he had to set the record straight, in regard to this story, “The Whipping”“, from Shock SuspenStories No. 14 (1954), and every other similar story they“d created: “This is one of a series of stories designed to show the evils of race prejudice and mob violence, in this case against Mexican Catholics. Previous stories in this same magazine had dealt with antisemitism, and anti-Negro feelings”¦ and development of juvenile delinquents. This is one of the most brilliantly written stories that I have had the pleasure to publish. I was very proud of it, and to find it being used in such a nefarious way made me quite angry.”“ Bill pointed out that censorship of media was par for the course in Communist dictatorships and not only there. Even as early as 1940, when comics had experienced a meteoric rise in popularity, articles had appeared which argued that comics were “A National Disgrace.”“ As a reaction, not unlike the burning of the works of literature from celebrated authors organized under the fascist rule in Germany at the same time, comic book burnings were held across the United States. In 1954, only a few years later, here was a televised witch hunt trial, and Gaines was right in the middle of it. He had to be. Unfortunately, Bill was also on too much Benzedrine, and he soon lost his focus once the questioning by Senator Estes Kefauver began who deftly lured him away from the point on societal ills and the importance of freedom of speech he was making and who instead confronted him with what became EC“s most notorious cover, namely a cover depicting a man with a bloody axe holding the head of a blonde woman by her hair. Ironically, Gaines had stepped in prior to its publication to prevent the illustration from showing the severed neck of the victim as artist Johnny Craig had originally intended. Nevertheless, once the Senator tricked him into stating that in his opinion the cover was in “good taste”“, Bill never got the chance to explain what he“d had wanted to achieve once he“d decided to let Feldstein write stories like “The Whipping”“. As he“d stated earlier, before the Benzedrine made him drowsy and severely unfocused, they“d created a whole series of tales that dealt with some of the hot button issues plaguing the American Society and National Psyche in those days, and unfortunately to this day. Gaines could not know this of course, and most likely he was hoping for a better outcome when shortly after he and Feldstein had started yet another title for their popular New Trend line, they set out to create a type of tales that was different to what they“d done earlier, stories which were educational, stories that in function were not unlike the educator they“d introduce readers to in “Judgment Day”“, the difference being that Gaines and Feldstein“s educational stories were not intended to tell readers to simply accept the way the world was, but to go and change it. As Feldstein would show in “Judgment Day”“ just a year later, when Tarlton very overtly lets his mechanical escort know, that yes, one lone orange robot could help bring about positive change, the same was true for every boy and girl who read these tales. When they started their latest title, Shock SuspenStories though, this wasn“t on their minds right away. In lieu of a letters column, Gaines and Feldstein used the page in the first issue to explain why there was a new title in the first place: “Well! Here it is! The Magazine we HOPE you“ve been waiting for! This is E.C.“s latest effort and we“ve worked hard on it.”“ They then went on to explain that many readers had written in to request more yarns in the genre they enjoyed most: “Many of you wanted another science-fiction mag, you horror fans wanted another horror book and you suspense readers wanted a companion mag to Crime SuspenStories!”“ We decided therefore to make this new mag an ”˜E.C. SAMPLER“ and to include in it a S-F yarn, a horror tale, a Crime SuspenStory, and”¦ a war story”¦ all of you fans seemed to agree on one thing: all of you wanted stories to have the usual E.C. SHOCK endings!… So what could be more natural than to call the magazine SHOCK SUSPENSTORIES?”“ To reflect such wide-ranging type of content from across such diverse genres, Gaines and his editor-writer had assembled a deep bench of talent for their premier issue: Jack Kamen, Jack Davis, Joe Orlando and Graham Ingels. Then something changed. When readers spied the second issue at their local supermarket or drugstore, they discovered that here was a new element at play. Though they might not have been able to name it, what this was, was social commentary and it was right there on the cover by Wally Wood. With some soldiers parading far in the background who seemed strangely oblivious to what was going on at the center of this tableau, almost as if they were tin figurines or not at liberty to deviate from their orders or devoid of compassion, there was also a mob of people, though as depicted by Wood, these were no faceless men or women. What they were was a loose assemblage of individuals, perfectly rendered by the artist as such who also made each person look rather mundane. These were bank tellers, insurance brokers, car salesman, neighbors, homemakers and career girls. There were also two children present, a little girl who anxiously reached with both hands for the coat of the adult female standing next to her while she still looked on. And one fair-haired boy whose intent gaze betrayed his dark fascination with what was going on. These people came from all walks of life, and they were fathers and mothers, yet here they were, united by a common cause and almost frothing at the mouth while they were brutally mauling one who seemed like one of their own, another common man, except for the fact that he wasn“t. There were some men, attractive and rugged despite their business suits, who were punching and kicking him though he was already on the ground, his arms and hands stretched out to protect himself, but also in a gesture that was pleading with his savage assailants who called him “a dirty red”“. Still there was one man who spoke up in defense of this poor soul. He was an older fellow who tried to stand very straight, yet with many from the crowd pushing forward, he swayed like a brittle leaf in a storm. Undeterred by the hatred which surrounded him and everybody else, hatred that was swiftly born from righteous indignation and which in turn had begotten ignorance and violent deeds, this man who ignored the danger he put himself into, cautioned his fellow men, as he begged: “Stop it! Please! What you“re doing is wrong! Act like Americans!”“, though on this cover at least and in this powerful, visceral depiction there would be no change. It was America, alright, but in a Norman Rockwell dream gone wrong. This was neighbor versus neighbor, and brother against brother. What was any young reader to make of this? Grab your mother“s coat and still keep on looking? Or to derive some dark satisfaction from this apparent red agent getting what he had coming?