“THE BEAUTY OF UGLINESS“ A COLUMN ABOUT EC COMICS, PART 7

Something weird happens when we imagine what a creator of genre fiction might be like or we envision what sort of life such a writer or artist may lead. When we visualize a crime writer for instance, we think of a fellow who used to be a reporter on the city beat. A guy with contacts, who hounded beat cops for news stories outside a local precinct late at night. A man who would not shy away from even going to the city morgue for the latest scoop. Or in our mind we“ll conjure up a guy who once was a detective, a gumshoe with a hat on his head, clad in a long trench coat to shield his cheap suit from the rain and for him to hide that he wore his heart in the right place. Many moons ago, he had been on the force himself, but he had ample motive to have quit his service, very often because his own moral code clashed with what was going on at the station. The racism, the corruption, the incompetence. Or he once was a cocky rebel who the army had failed to straighten out and who needed the structure an employer could award him, and the comfort a company of like-minded brothers offered. He“d sign up with a  detective agency for a bit. Yet following unfaithful wives or straying husbands or bashing in the heads of migrant workers on strike was not his brand of justice. In the end he found out that he was a loner who could tolerate a group of people just for a couple of hours a day. Thus, the writer of crime fiction would use a typewriter instead of a gun and words became his bullets, while he still wore his hat. And with his work for the day done, he“d show up at the watering hole from around the lonely apartment complex he lived in. He was a stiff drinker who could pack away the bourbon. From a bar stool he“d reminisce about the old days or drink in silence. He knew it all and he had seen it all. Even when the success of the pulp magazines made him a star, he“d remain dedicated to his craft. Like writer Walter B. Gibson who had been commissioned by publisher Street & Smith to come up with stories centered around what was essential only the voice of a mysterious narrator on a radio program. Taking on the house name Maxwell Grant, Gibson not only wrote almost three hundred novels about The Shadow, this violent vigilante who was perfect for a time when cities were growing, and starving readers wanted to escape from the depression their lives were in once the stock market had crashed, but he himself got rich like his lead character. Still, Gibson would not rest, not even once he“d carved out an affluent life for himself. He“d position one Corona typewriter in each room of his sumptuous estate, not for show (he was a spokesperson for the manufacturer), but to be ready to continue with a novel whenever inspiration struck him. But he stayed a loner, he had to be for his work. The crime writer, like the detective or the young rookie who solves the case, became a romantic ideal. Even though he opened up worlds of hardboiled action to readers, nobody thought that he had ever committed a crime. This was all fiction but taken from real life. And if a writer came from a background of espionage, like Graham Green, a spy for MI6 who masked as a journalist, or Ian Fleming who had worked for the British version of the CIA, it only made the stories much more exciting, and all was forgiven by an adoring public. Men who put forth such riveting accounts were considered romantic loners and well-mannered, well-dressed gentlemen. Likewise, nobody expected science fiction writers like a H.G. Wells to have travelled through time or to have met any real Martians. Whenever Edgar Rice Burroughs opened the door to another fantastic world or the African jungle, nobody thought this weird, and nobody expected a middle-aged guy like him to have visited exotic locations that only existed in his mind and which now also existed in the imagination of readers. All these men were well respected and received invitations to cocktail parties and many fan letters alike. And the same holds true for the men who began to put pictures to their words for newspaper strips, men like Alex Raymond, Milt Caniff and Hal Foster. Nobody considered such revered artists strange or outsiders who either shunned society or had to be kept away from normal folk and children especially. And this statement equally applies to the many men (and sometimes a woman, too, like Lee Brackett) who worked for the science fiction pulps, some of which would eventually make the transition from prose writer to comic scripter. Eando Binder, Gardner Fox and other science fiction authors are still held in regard from one generation of fans to the next whenever they discover their work. And men and women who wrote western tales in which brave cowboys slaughtered Native Americans wholesale, and with abandon, do not stand accused of racism, but are considered chronologists who help to remind us of a thrilling part of history when the West was won. Crime Fiction, Science Fiction and even Western Tales are safe spaces of genre fiction. As a creator you are able to walk up to somebody at a party and say with pride: “I wrote this.”“ But where the other pillar is concerned on which the house of genre fiction rests, most writers and artists wouldn“t consider themselves this lucky. If you wrote horror tales or if your art depicted things from the nightmare realm of our collective subconscious mind, something had to be wrong with you. Maybe there was a childhood trauma you hadn“t successfully overcome even as an adult, or you were a sadist or a sociopath or worse. You“d been able to walk among mentally healthy, stable men undetected so far, but since you ventured into such bizarre worlds as you were wont to depict in your fiction, you simply had to be in league with an arcane force. Why else would you choose to spend your professional life in nauseating places where there were no heroes, but darkness? There had to be something wrong with you, and nobody expected your own lifestyle to be a healthy one either. A person who wrote or drew horror stories had to be one human specimen with an unsound mind. Authors like Greene and Fleming and numerous other writers, who hit the keyboards of their typewriters hard and fast, had personal experiences to share. What did you do or what was done to you that you regularly ventured to dark places, and that you even expected readers to be entertained by horrors such as those that were born from your dark soul? Surely, you had to be a freak of some sorts. No sane person would be spending their waking hours to think up innovative ways by which body parts could be torn from a human torso or be attached to it in some kind of unholy manner or the undead leaving their moldy graves to come for the living. Horror was the domain of the ill-adapt, the crazy ones, the misfits in society. And for a horror creator, there was no place at the table.

detective agency for a bit. Yet following unfaithful wives or straying husbands or bashing in the heads of migrant workers on strike was not his brand of justice. In the end he found out that he was a loner who could tolerate a group of people just for a couple of hours a day. Thus, the writer of crime fiction would use a typewriter instead of a gun and words became his bullets, while he still wore his hat. And with his work for the day done, he“d show up at the watering hole from around the lonely apartment complex he lived in. He was a stiff drinker who could pack away the bourbon. From a bar stool he“d reminisce about the old days or drink in silence. He knew it all and he had seen it all. Even when the success of the pulp magazines made him a star, he“d remain dedicated to his craft. Like writer Walter B. Gibson who had been commissioned by publisher Street & Smith to come up with stories centered around what was essential only the voice of a mysterious narrator on a radio program. Taking on the house name Maxwell Grant, Gibson not only wrote almost three hundred novels about The Shadow, this violent vigilante who was perfect for a time when cities were growing, and starving readers wanted to escape from the depression their lives were in once the stock market had crashed, but he himself got rich like his lead character. Still, Gibson would not rest, not even once he“d carved out an affluent life for himself. He“d position one Corona typewriter in each room of his sumptuous estate, not for show (he was a spokesperson for the manufacturer), but to be ready to continue with a novel whenever inspiration struck him. But he stayed a loner, he had to be for his work. The crime writer, like the detective or the young rookie who solves the case, became a romantic ideal. Even though he opened up worlds of hardboiled action to readers, nobody thought that he had ever committed a crime. This was all fiction but taken from real life. And if a writer came from a background of espionage, like Graham Green, a spy for MI6 who masked as a journalist, or Ian Fleming who had worked for the British version of the CIA, it only made the stories much more exciting, and all was forgiven by an adoring public. Men who put forth such riveting accounts were considered romantic loners and well-mannered, well-dressed gentlemen. Likewise, nobody expected science fiction writers like a H.G. Wells to have travelled through time or to have met any real Martians. Whenever Edgar Rice Burroughs opened the door to another fantastic world or the African jungle, nobody thought this weird, and nobody expected a middle-aged guy like him to have visited exotic locations that only existed in his mind and which now also existed in the imagination of readers. All these men were well respected and received invitations to cocktail parties and many fan letters alike. And the same holds true for the men who began to put pictures to their words for newspaper strips, men like Alex Raymond, Milt Caniff and Hal Foster. Nobody considered such revered artists strange or outsiders who either shunned society or had to be kept away from normal folk and children especially. And this statement equally applies to the many men (and sometimes a woman, too, like Lee Brackett) who worked for the science fiction pulps, some of which would eventually make the transition from prose writer to comic scripter. Eando Binder, Gardner Fox and other science fiction authors are still held in regard from one generation of fans to the next whenever they discover their work. And men and women who wrote western tales in which brave cowboys slaughtered Native Americans wholesale, and with abandon, do not stand accused of racism, but are considered chronologists who help to remind us of a thrilling part of history when the West was won. Crime Fiction, Science Fiction and even Western Tales are safe spaces of genre fiction. As a creator you are able to walk up to somebody at a party and say with pride: “I wrote this.”“ But where the other pillar is concerned on which the house of genre fiction rests, most writers and artists wouldn“t consider themselves this lucky. If you wrote horror tales or if your art depicted things from the nightmare realm of our collective subconscious mind, something had to be wrong with you. Maybe there was a childhood trauma you hadn“t successfully overcome even as an adult, or you were a sadist or a sociopath or worse. You“d been able to walk among mentally healthy, stable men undetected so far, but since you ventured into such bizarre worlds as you were wont to depict in your fiction, you simply had to be in league with an arcane force. Why else would you choose to spend your professional life in nauseating places where there were no heroes, but darkness? There had to be something wrong with you, and nobody expected your own lifestyle to be a healthy one either. A person who wrote or drew horror stories had to be one human specimen with an unsound mind. Authors like Greene and Fleming and numerous other writers, who hit the keyboards of their typewriters hard and fast, had personal experiences to share. What did you do or what was done to you that you regularly ventured to dark places, and that you even expected readers to be entertained by horrors such as those that were born from your dark soul? Surely, you had to be a freak of some sorts. No sane person would be spending their waking hours to think up innovative ways by which body parts could be torn from a human torso or be attached to it in some kind of unholy manner or the undead leaving their moldy graves to come for the living. Horror was the domain of the ill-adapt, the crazy ones, the misfits in society. And for a horror creator, there was no place at the table.

For any creator of fiction, there seems to be a certain narrative that goes with his or her life, one which helps to explain how such a person came to be and how such works of fiction could have come about. People who lack any form of imagination, need to know. They demand an explanation. And where many creators are concerned who work in horror fiction, the public, a clever publisher or urban legends will gladly fill in the blank spaces that may exist around such a creator“s biography and to furnish a reasoning if one is missing. When Mary Shelley published her novel “Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus”“ in 1818, she was just  twenty. She“d begun working on the book when she was only eighteen years old. Wisely though, she had her name not appear on the book“s cover which saw print anonymously. Only once the book had found critical acclaim and was discussed even in society“s highest circles, albeit in a hushed tone of voice, did she put her name to the second edition which saw print five years later. Mary was now older and married to one of England“s most respected poets, and she herself was the offspring of a family of intellectuals which helped explain such an outlandish piece of fiction. Still, there needed to be a story to go with the book. Thus, the legend of that one night was created during which she and her future husband Percy B. Shelley and their friend, infant terrible Lord Byron, who was in a love affair with his half-sister, told each other horror tales. With a fierce storm raging outside their eccentric host“s mansion in Switzerland, overlooking Lake Geneva, and having come off a long trip across Germany, the young girl“s mind was surely stimulated in such a manner that Dr. Frankenstein and his unfortunate and ghastly misshapen monster would see their most unnatural birth from raw imagination. Certainly, one can envision many variations of opiates which most assuredly must have been in ample supply to those in attendance. Many years later, when Hollywood came calling, the director chosen to helm the movie that bore the scientist“s name, but which long since has become synonymous with the monster himself, forsook his once promising career in A-pictures. He, too, like author Mary Shelley, is solely remembered for his entanglement with this vile monstrosity. A man who not only made such a movie, but who then created a sequel to his original film four years later, one which surpassed his first offering by leaps and bounds and then some, surely could not have been of a right state of mind. And according to the moral standards of those days (perhaps were some individuals are concerned even by today“s), director James Whale wasn“t. He was one of the few creatives in the Hollywood community who, among this exclusive circle, lived openly homosexual. This was of course something which contributed to the legend of James Whale“s downfall, along with his decision to work in horror pictures. After Whale had started his career with so much promise. Carl Laemmle, the head of the studio behind the two Frankenstein movies, which became massive financial hits, offered him the director“s chair for “Dracula“s Daughter”“. But now wary of getting typecast, he opted for a movie called “Remember Last Night?”“, a comedic twist on a whodunit in the vein of Dashiell Hammett“s “The Thin Man”“. The film garnered mixed reviews. Whale went back to do a prestige production one last time in 1937 with “The Road Back”“. However, the title proved ironic in that there wasn“t a road back for the highly gifted director. With Nazi Germany threatening Universal Pictures with a boycott (the Laemmle family had filed for bankruptcy and had subsequently lost control of the studio), an alternative cut was completed without Whale“s involvement. Still, the movie was not only banned in Germany and Austria, but due to the involvement of the Nazi Party in many other places such as China, Italy and Switzerland. Whale made one more movie, another genre piece, but effectively his career was over. David Lewis, who was a successful producer, and James Whale“s long-time romantic partner, would support him financially. Then Whale met a barkeeper, a hustler by all accounts. Ending his relationship of twenty-three years with Lewis, the erstwhile film director, who was sixty-two, started dating the twenty-five-year-old Pierre Foegel, whom Whale employed as a chauffeur. Still, Lewis bought Whale a house in California and had a swimming pool dug for his former lover. Foegel, now working at the run-down gas station Whale owned, and the much older man began throwing all-male pool parties and carried on with their romance. Suffering a stroke and getting more and more depressed as a result, the man who“d recreated Shelly“s Frankenstein for Hollywood, drowned himself in his swimming pool.

twenty. She“d begun working on the book when she was only eighteen years old. Wisely though, she had her name not appear on the book“s cover which saw print anonymously. Only once the book had found critical acclaim and was discussed even in society“s highest circles, albeit in a hushed tone of voice, did she put her name to the second edition which saw print five years later. Mary was now older and married to one of England“s most respected poets, and she herself was the offspring of a family of intellectuals which helped explain such an outlandish piece of fiction. Still, there needed to be a story to go with the book. Thus, the legend of that one night was created during which she and her future husband Percy B. Shelley and their friend, infant terrible Lord Byron, who was in a love affair with his half-sister, told each other horror tales. With a fierce storm raging outside their eccentric host“s mansion in Switzerland, overlooking Lake Geneva, and having come off a long trip across Germany, the young girl“s mind was surely stimulated in such a manner that Dr. Frankenstein and his unfortunate and ghastly misshapen monster would see their most unnatural birth from raw imagination. Certainly, one can envision many variations of opiates which most assuredly must have been in ample supply to those in attendance. Many years later, when Hollywood came calling, the director chosen to helm the movie that bore the scientist“s name, but which long since has become synonymous with the monster himself, forsook his once promising career in A-pictures. He, too, like author Mary Shelley, is solely remembered for his entanglement with this vile monstrosity. A man who not only made such a movie, but who then created a sequel to his original film four years later, one which surpassed his first offering by leaps and bounds and then some, surely could not have been of a right state of mind. And according to the moral standards of those days (perhaps were some individuals are concerned even by today“s), director James Whale wasn“t. He was one of the few creatives in the Hollywood community who, among this exclusive circle, lived openly homosexual. This was of course something which contributed to the legend of James Whale“s downfall, along with his decision to work in horror pictures. After Whale had started his career with so much promise. Carl Laemmle, the head of the studio behind the two Frankenstein movies, which became massive financial hits, offered him the director“s chair for “Dracula“s Daughter”“. But now wary of getting typecast, he opted for a movie called “Remember Last Night?”“, a comedic twist on a whodunit in the vein of Dashiell Hammett“s “The Thin Man”“. The film garnered mixed reviews. Whale went back to do a prestige production one last time in 1937 with “The Road Back”“. However, the title proved ironic in that there wasn“t a road back for the highly gifted director. With Nazi Germany threatening Universal Pictures with a boycott (the Laemmle family had filed for bankruptcy and had subsequently lost control of the studio), an alternative cut was completed without Whale“s involvement. Still, the movie was not only banned in Germany and Austria, but due to the involvement of the Nazi Party in many other places such as China, Italy and Switzerland. Whale made one more movie, another genre piece, but effectively his career was over. David Lewis, who was a successful producer, and James Whale“s long-time romantic partner, would support him financially. Then Whale met a barkeeper, a hustler by all accounts. Ending his relationship of twenty-three years with Lewis, the erstwhile film director, who was sixty-two, started dating the twenty-five-year-old Pierre Foegel, whom Whale employed as a chauffeur. Still, Lewis bought Whale a house in California and had a swimming pool dug for his former lover. Foegel, now working at the run-down gas station Whale owned, and the much older man began throwing all-male pool parties and carried on with their romance. Suffering a stroke and getting more and more depressed as a result, the man who“d recreated Shelly“s Frankenstein for Hollywood, drowned himself in his swimming pool.

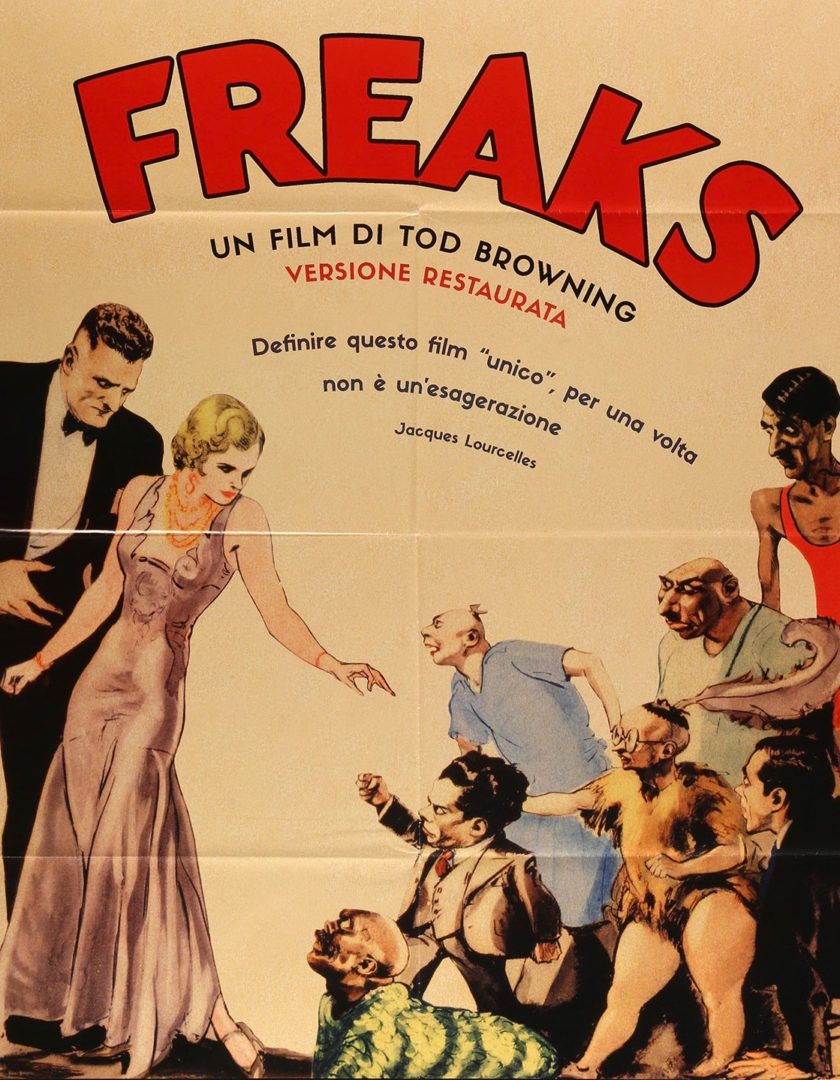

Tod Browning, the movie director who had brought the other immensely popular horror icon into the lives of many Americans and millions of people around the globe, when he directed “Dracula”“ in 1930 for Universal, decided to venture deeper still into the world of horror. Born Charles Albert Browning Jr., he changed his name to Tod (the German word for “Death”“) when, at the age of sixteen, he was working as a performer in sideshows, carnivals and circuses, a life which had been fascinating Browning from an early age on. After a successful career in silent films with leading horror star Lon Chaney, and with such a massive hit as “Dracula”“ had turned out to be, Browning was free to choose his next project. What he wanted to do, though, was to go back to that strange life of the little men  who performed at the circus. And “little men”“ was not only meant in a sense of coming from a socially low station in life, but literally. Browning was developing a film based on a short story which dealt with a love triangle set in this world, but in a way that would become highly seminal for many horror stories and especially horror comics to follow. This was a story about a circus strongman, a beautiful blonde aerialist and a wealthy dwarf. Tod Browning intended for the film to be shot in the most naturalistic manner. This included casting several real-life circus acts, including a pair of conjoined twins, two sisters known as “armless wonders”“, a cross-dresser, a human skeleton, and a number of midgets. Browning himself had convinced rival studio MGM to purchase the rights to the story, and he sold Irving Thalberg, MGM“s wunderkind head of production, into making the movie with him directing. Thalberg agreed based on the director“s previous successes, but he abandoned the idea of casting major stars in addition to the cast Browning was putting together, much to the dismay of some of the fellow actors at the studio who were up in arms about such a strange choice of players and who in part refused to frequent the cafeteria as long as Tod Browning and his cast were around. As far as the movie itself was concerned, Browning kept close to the source material. This was the story of beautiful performer Cleopatra, played by Olga Baclanova, an actress and ballerina who had made a name for herself during the silent film era, the dwarf Hans whom she marries for his money and strongman Hercules who she loves for his body. Cleopatra has just joined the circus when she learns about the inheritance that has made Hans rich. Getting in-between Hans and the loyal, equally midget-sized Frieda, Cleopatra seduces Hans who gladly agrees to marry the much taller woman, though among his friends, Cleopatra is the outsider. Nevertheless, with Hans happy and willing to vouch for her, she is accepted into this sub-set of circus performers as one of them. That is till the loyal Frieda and his friends find out about Cleopatra“s infidelity, and her scheme to slowly poison her husband to his death. This is when the film turns. People who enlisted pity and a sense of shame from us, the viewers, hunt and then brutally murder Hercules. While this seems unnecessary cruel and petty, considering that Hercules isn“t much more than a bully who owes Hans no loyalty, the physically challenged performers do reserve the most brutal and inhumane punishment for the attractive blonde woman. Sold with a movie poster that showed the beautiful aerialist seated, with the doll-sized Hans placed in her lap, and a salacious tagline (“Can a full grown woman truly love a midget?”“), the twist ending may well have served as a progenitor to many horror yarns to come from EC Comics twenty years later. Shortly before Browning ends his film “Freaks”“ (1932), we see that it is Cleopatra who is put on display. The carnival acts who had our pity for so long, are now as freakish and gruesome in their behavior as they are in appearance. Without remorse they have transformed the unfaithful Cleopatra into a sideshow attraction. The once beautiful woman has been permanently tarred and feathered, the flesh of her hands has been deformed to look like the feet of a duck, her legs have been sawed off, and her tongue has been removed. With one of her eyes brutally gouged out, the half-blind woman can only partly see the terror and perverse curiosity that she causes on the faces of the patrons who stare at this “human chicken”“. And then, once again very much like at the end of many horror tales in the comic books from EC Comics that were far off into the future, the film tells us about the fate of the one who was wronged so severely, only because he had fallen for a beautiful, but very dishonest woman. Hans, now living in the mansion his inheritance had bought him, was happily reunited with Frieda who clearly was more of a woman than the aerialist ever was. “Freaks”“ managed to do what a car accident early into Tod“s career was unable to do. In 1915, the director drove his car at full speed into another vehicle, killing two actors who were with him, and severely injuring a third. Though he needed two years to recover from the injuries he himself had sustained, Browning was working on movie scripts. After a screening of “Freaks”“ to a test audience in 1931, the director was fifty-one and looking back on a career during which he had directed nearly sixty films, the support was gone. People reacted with shock and disbelief to his film. The studio quickly ordered massive cuts to be made to Tod“s movie, which ran ninety minutes. MGM even had to film additional scenes to reintroduce some of the connective tissue for the narrative to still make sense after so much material had been expunged. A sixty-four-minute-long version was eventually released in the States, with the original cut ordered to be destroyed. Though some reviewers actually praised Browning for casting people with real disabilities as eponymous characters in the movie, the controversial subject matter of “Freaks”“ and the reactions from a stunned general audience, was a bridge to far. To put this into perspective, the film was banned in the United Kingdom for thirty years. Soon Tod Browning shared a fate akin to that of filmmaker Erich von Stroheim, a director who became unpopular when he began to address very adult subject matters in his films, and who saw himself fired by Gloria Swanson, a star whose career he“d helped to establish. Though, von Stroheim remained in high demand as an actor for the role of a sadistic villain. The director of “Freaks”“ only wished he was this lucky. After a few lackluster films, his career was dead. He died ten years later. Interestingly, “Dracula”“ and “Freaks”“ are the two movies Browning is best remembered for. To have your films too closely associated with your person or your private life, until the borders became blurred, at least in the eyes of the public, proved the downfall of British director Michael Powell whose work great directors up to today name as a source of influence. Powell had been working in the British film industry for thirty-five years (literally starting as the kid who got the coffee), when in 1960 he made the film “Peeping Tom”“, a flick that was so ahead of its time that it preceded films like John Carpenter“s “Halloween”“ and many slasher movies of the 80s by almost two decades. By releasing a movie which is not only widely considered a classic today, but one that proved way too controversial for its time, much like Browning“s “Freaks”“, Powell effectively killed his career and that of his male lead Carl Böhm. There simply had to be something wrong with men who would come up with such depraved subject matters.

who performed at the circus. And “little men”“ was not only meant in a sense of coming from a socially low station in life, but literally. Browning was developing a film based on a short story which dealt with a love triangle set in this world, but in a way that would become highly seminal for many horror stories and especially horror comics to follow. This was a story about a circus strongman, a beautiful blonde aerialist and a wealthy dwarf. Tod Browning intended for the film to be shot in the most naturalistic manner. This included casting several real-life circus acts, including a pair of conjoined twins, two sisters known as “armless wonders”“, a cross-dresser, a human skeleton, and a number of midgets. Browning himself had convinced rival studio MGM to purchase the rights to the story, and he sold Irving Thalberg, MGM“s wunderkind head of production, into making the movie with him directing. Thalberg agreed based on the director“s previous successes, but he abandoned the idea of casting major stars in addition to the cast Browning was putting together, much to the dismay of some of the fellow actors at the studio who were up in arms about such a strange choice of players and who in part refused to frequent the cafeteria as long as Tod Browning and his cast were around. As far as the movie itself was concerned, Browning kept close to the source material. This was the story of beautiful performer Cleopatra, played by Olga Baclanova, an actress and ballerina who had made a name for herself during the silent film era, the dwarf Hans whom she marries for his money and strongman Hercules who she loves for his body. Cleopatra has just joined the circus when she learns about the inheritance that has made Hans rich. Getting in-between Hans and the loyal, equally midget-sized Frieda, Cleopatra seduces Hans who gladly agrees to marry the much taller woman, though among his friends, Cleopatra is the outsider. Nevertheless, with Hans happy and willing to vouch for her, she is accepted into this sub-set of circus performers as one of them. That is till the loyal Frieda and his friends find out about Cleopatra“s infidelity, and her scheme to slowly poison her husband to his death. This is when the film turns. People who enlisted pity and a sense of shame from us, the viewers, hunt and then brutally murder Hercules. While this seems unnecessary cruel and petty, considering that Hercules isn“t much more than a bully who owes Hans no loyalty, the physically challenged performers do reserve the most brutal and inhumane punishment for the attractive blonde woman. Sold with a movie poster that showed the beautiful aerialist seated, with the doll-sized Hans placed in her lap, and a salacious tagline (“Can a full grown woman truly love a midget?”“), the twist ending may well have served as a progenitor to many horror yarns to come from EC Comics twenty years later. Shortly before Browning ends his film “Freaks”“ (1932), we see that it is Cleopatra who is put on display. The carnival acts who had our pity for so long, are now as freakish and gruesome in their behavior as they are in appearance. Without remorse they have transformed the unfaithful Cleopatra into a sideshow attraction. The once beautiful woman has been permanently tarred and feathered, the flesh of her hands has been deformed to look like the feet of a duck, her legs have been sawed off, and her tongue has been removed. With one of her eyes brutally gouged out, the half-blind woman can only partly see the terror and perverse curiosity that she causes on the faces of the patrons who stare at this “human chicken”“. And then, once again very much like at the end of many horror tales in the comic books from EC Comics that were far off into the future, the film tells us about the fate of the one who was wronged so severely, only because he had fallen for a beautiful, but very dishonest woman. Hans, now living in the mansion his inheritance had bought him, was happily reunited with Frieda who clearly was more of a woman than the aerialist ever was. “Freaks”“ managed to do what a car accident early into Tod“s career was unable to do. In 1915, the director drove his car at full speed into another vehicle, killing two actors who were with him, and severely injuring a third. Though he needed two years to recover from the injuries he himself had sustained, Browning was working on movie scripts. After a screening of “Freaks”“ to a test audience in 1931, the director was fifty-one and looking back on a career during which he had directed nearly sixty films, the support was gone. People reacted with shock and disbelief to his film. The studio quickly ordered massive cuts to be made to Tod“s movie, which ran ninety minutes. MGM even had to film additional scenes to reintroduce some of the connective tissue for the narrative to still make sense after so much material had been expunged. A sixty-four-minute-long version was eventually released in the States, with the original cut ordered to be destroyed. Though some reviewers actually praised Browning for casting people with real disabilities as eponymous characters in the movie, the controversial subject matter of “Freaks”“ and the reactions from a stunned general audience, was a bridge to far. To put this into perspective, the film was banned in the United Kingdom for thirty years. Soon Tod Browning shared a fate akin to that of filmmaker Erich von Stroheim, a director who became unpopular when he began to address very adult subject matters in his films, and who saw himself fired by Gloria Swanson, a star whose career he“d helped to establish. Though, von Stroheim remained in high demand as an actor for the role of a sadistic villain. The director of “Freaks”“ only wished he was this lucky. After a few lackluster films, his career was dead. He died ten years later. Interestingly, “Dracula”“ and “Freaks”“ are the two movies Browning is best remembered for. To have your films too closely associated with your person or your private life, until the borders became blurred, at least in the eyes of the public, proved the downfall of British director Michael Powell whose work great directors up to today name as a source of influence. Powell had been working in the British film industry for thirty-five years (literally starting as the kid who got the coffee), when in 1960 he made the film “Peeping Tom”“, a flick that was so ahead of its time that it preceded films like John Carpenter“s “Halloween”“ and many slasher movies of the 80s by almost two decades. By releasing a movie which is not only widely considered a classic today, but one that proved way too controversial for its time, much like Browning“s “Freaks”“, Powell effectively killed his career and that of his male lead Carl Böhm. There simply had to be something wrong with men who would come up with such depraved subject matters.

But then what about the grandfather of not only the detective story but of the horror story, the master of the macabre whose work would be studied and emulated by generations of filmmakers, authors and college students hence? If Mary Shelley broke new ground, her contemporary Edgar Allan Poe planted his flag right there. Surely, a person who created such outlandish tales of terror had to be a particularly weird individual, a guy who sleeps in graveyards and got high in an opium den. Well, Poe did come from a broken home. So really, you can“t be too shocked to learn that he must have had a twisted personality. When Edgar was  one year old, his father abandoned his family, never to be heard from again. And only one year later, his mother fell ill and died. The boy was raised by a foster family, that of John Allan, who hailed from Richmond, Virginia and who had established himself as a successful merchant. Though, the boy was welcomed into his new family, his new life took him far away from Boston where he was born. The Allans never officially adopted him, though they gave him the name Edgar Allan Poe. John, his new foster father had a peculiar way of treating his foster son. He would spoil him with presents, and on the next day he would discipline the boy rather harshly. What a strange life it was. John Allan accumulated his wealth through trade deals for anything from tobacco, cloth, tombstones and slaves. Clearly lacking structure, young Edgar was a bit of a dreamer, the lad would soon find himself on course to a career in the army. At the age of fifteen, Poe served as a lieutenant of the Richmond youth honor guard to please his foster father. During this time, John Allan inherited a nearly obscene amount of money, making him effectively one of the richest men in the state of Virginia. Edgar and he ran into trouble quickly, though. Once the boy had taken up studies at the University of Virginia, he needed ever more money from his foster father since he had developed a nasty gambling problem. When John eventually cut him off, the young man dropped out of college and joined the U.S. Army. What else was a guy supposed to do who had studied several semesters of ancient and modern languages and who found himself without funds? As for his private life, Poe married his cousin when she was only thirteen. The couple stayed together for eleven years until Virginia died prematurely. As for the demise of the author whose name eventually would become synonymous with morbid, imaginative tales of ghastly terror, the way his own life came to an end might very well have been inspired by one of his mysterious tales. On October 3, 1849, at the relatively young age of forty, Edgar Allan Poe was seen wandering the streets of Baltimore. Clearly Poe wasn“t well, and he appeared delirious. Poe was taken to a hospital where he came to only briefly, while screaming the name “Reynolds”“. Nobody around him had an idea who this person was or how Poe was involved with him or her. The author, whose last words were “Lord help my poor soul”“, died days later. With all medical records from those days lost, the cause of his death became a mystery in itself, though not much was known about the author either who was fiercely private. This however did not keep many from speculating about his demise, including many newspapers. Thus, there was enough fertile ground for intrigue when an obituary appeared soon after his death, one which painted him as a lunatic and as a psychopath who could be seen wandering the streets with cursing out every person he saw. The piece was soon circulated among other papers across the country. What made this obituary so fascinating to readers was, that finally here was proof what everyone familiar with his works, or having at least heard about them, thought of him. An author of such horrendous stories simply had to have been a drugged-out crazy person. Matters in this direction were further helped with a newly printed collection of Poe“s stories which appeared less than a year after his untimely death. In “Memoir of the Author”“, an article which served as a preface to the new collection of some of his works, Poe was portrayed as having been a depraved madman, a drug-addled pervert, who hung around abandoned churches and graveyards to soak up the flavors of decay. This biographical introduction to some of his most bizarre tales became a hit of its own. Not only did the biography get reprinted numerous times apart from the book, it helped to establish the conviction in people“s minds that only a barking, raving madman would have been able to come up with such outlandish tales. This was immensely thrilling for many readers. Then there were Poe“s letters which accompanied the article. The letters clearly backed it all up. He was indeed one sick individual it would seem. Having penned the original obituary, he had published under the pseudonym Ludwig, Poe“s long-time literary rival and arch-nemesis Rufus Wilmot Griswold quickly convinced Poe“s mother-in-law, Virginia“s mother, to sign any rights to Poe“s estate over to him. Finally, the day was his. Here was an opportunity to destroy his enemy“s name and to make some pretty coin while doing it. He didn“t even shy away from forging Poe“s letters to create a narrative that many readers soon embraced.

one year old, his father abandoned his family, never to be heard from again. And only one year later, his mother fell ill and died. The boy was raised by a foster family, that of John Allan, who hailed from Richmond, Virginia and who had established himself as a successful merchant. Though, the boy was welcomed into his new family, his new life took him far away from Boston where he was born. The Allans never officially adopted him, though they gave him the name Edgar Allan Poe. John, his new foster father had a peculiar way of treating his foster son. He would spoil him with presents, and on the next day he would discipline the boy rather harshly. What a strange life it was. John Allan accumulated his wealth through trade deals for anything from tobacco, cloth, tombstones and slaves. Clearly lacking structure, young Edgar was a bit of a dreamer, the lad would soon find himself on course to a career in the army. At the age of fifteen, Poe served as a lieutenant of the Richmond youth honor guard to please his foster father. During this time, John Allan inherited a nearly obscene amount of money, making him effectively one of the richest men in the state of Virginia. Edgar and he ran into trouble quickly, though. Once the boy had taken up studies at the University of Virginia, he needed ever more money from his foster father since he had developed a nasty gambling problem. When John eventually cut him off, the young man dropped out of college and joined the U.S. Army. What else was a guy supposed to do who had studied several semesters of ancient and modern languages and who found himself without funds? As for his private life, Poe married his cousin when she was only thirteen. The couple stayed together for eleven years until Virginia died prematurely. As for the demise of the author whose name eventually would become synonymous with morbid, imaginative tales of ghastly terror, the way his own life came to an end might very well have been inspired by one of his mysterious tales. On October 3, 1849, at the relatively young age of forty, Edgar Allan Poe was seen wandering the streets of Baltimore. Clearly Poe wasn“t well, and he appeared delirious. Poe was taken to a hospital where he came to only briefly, while screaming the name “Reynolds”“. Nobody around him had an idea who this person was or how Poe was involved with him or her. The author, whose last words were “Lord help my poor soul”“, died days later. With all medical records from those days lost, the cause of his death became a mystery in itself, though not much was known about the author either who was fiercely private. This however did not keep many from speculating about his demise, including many newspapers. Thus, there was enough fertile ground for intrigue when an obituary appeared soon after his death, one which painted him as a lunatic and as a psychopath who could be seen wandering the streets with cursing out every person he saw. The piece was soon circulated among other papers across the country. What made this obituary so fascinating to readers was, that finally here was proof what everyone familiar with his works, or having at least heard about them, thought of him. An author of such horrendous stories simply had to have been a drugged-out crazy person. Matters in this direction were further helped with a newly printed collection of Poe“s stories which appeared less than a year after his untimely death. In “Memoir of the Author”“, an article which served as a preface to the new collection of some of his works, Poe was portrayed as having been a depraved madman, a drug-addled pervert, who hung around abandoned churches and graveyards to soak up the flavors of decay. This biographical introduction to some of his most bizarre tales became a hit of its own. Not only did the biography get reprinted numerous times apart from the book, it helped to establish the conviction in people“s minds that only a barking, raving madman would have been able to come up with such outlandish tales. This was immensely thrilling for many readers. Then there were Poe“s letters which accompanied the article. The letters clearly backed it all up. He was indeed one sick individual it would seem. Having penned the original obituary, he had published under the pseudonym Ludwig, Poe“s long-time literary rival and arch-nemesis Rufus Wilmot Griswold quickly convinced Poe“s mother-in-law, Virginia“s mother, to sign any rights to Poe“s estate over to him. Finally, the day was his. Here was an opportunity to destroy his enemy“s name and to make some pretty coin while doing it. He didn“t even shy away from forging Poe“s letters to create a narrative that many readers soon embraced.

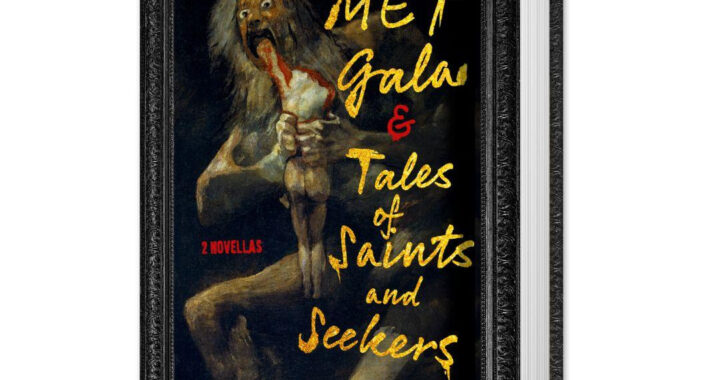

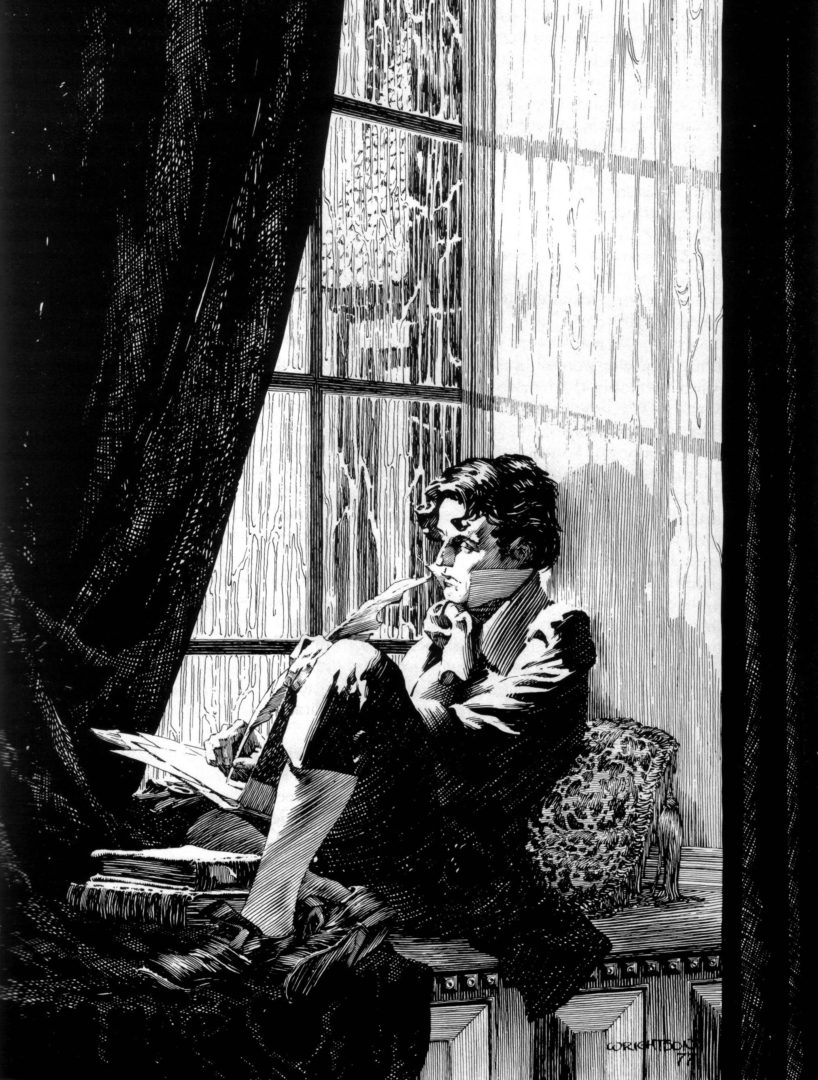

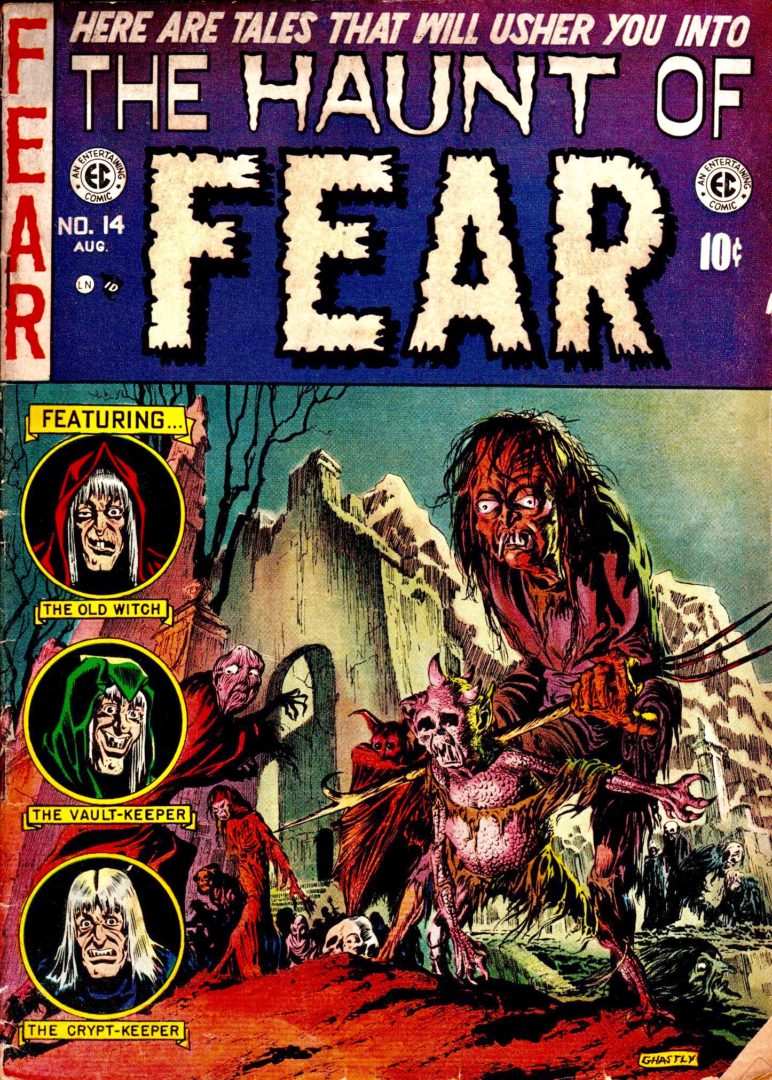

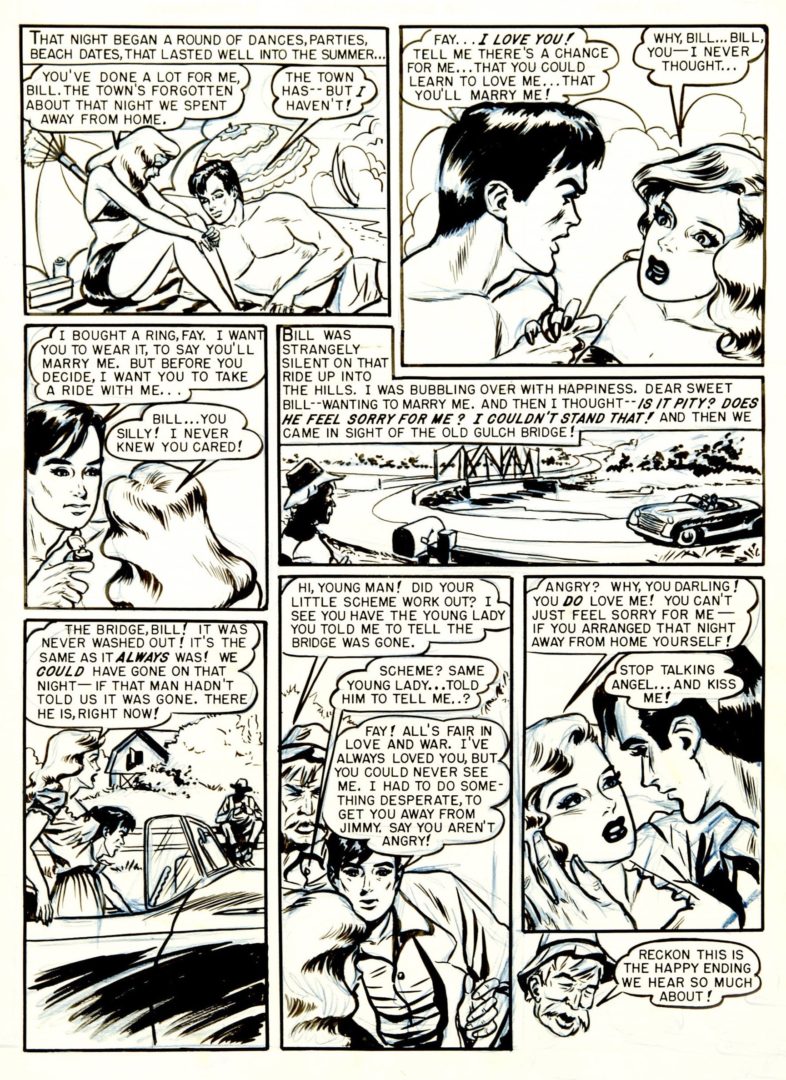

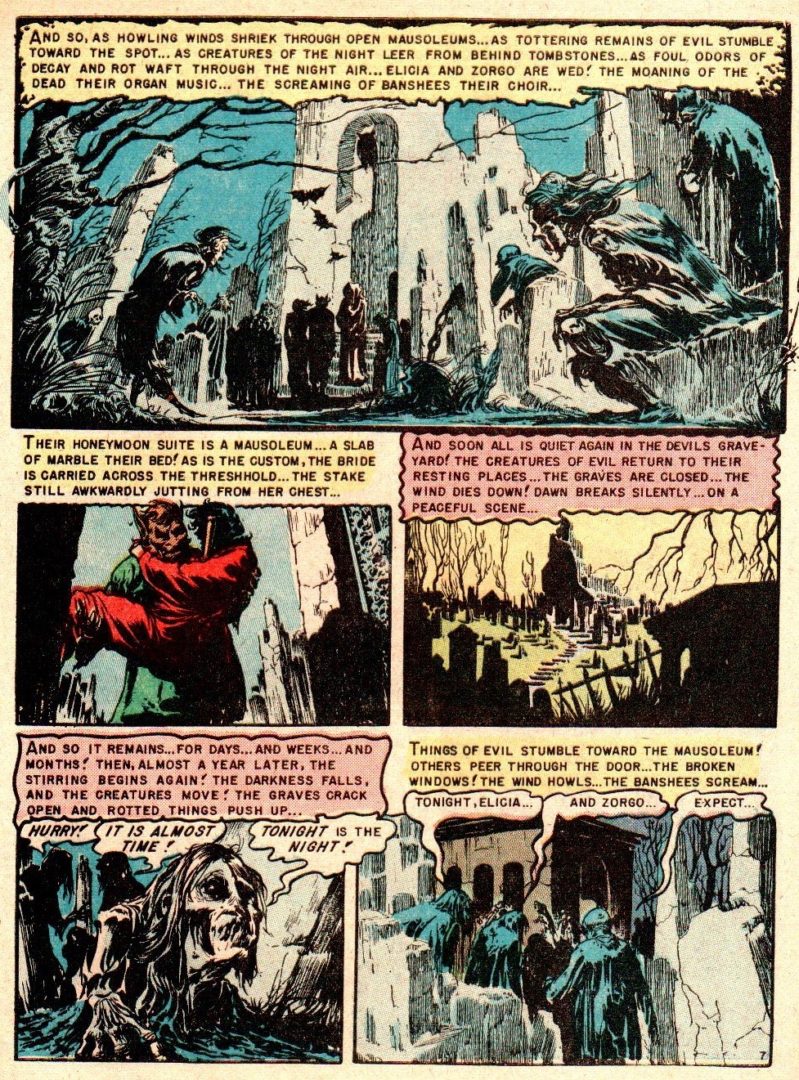

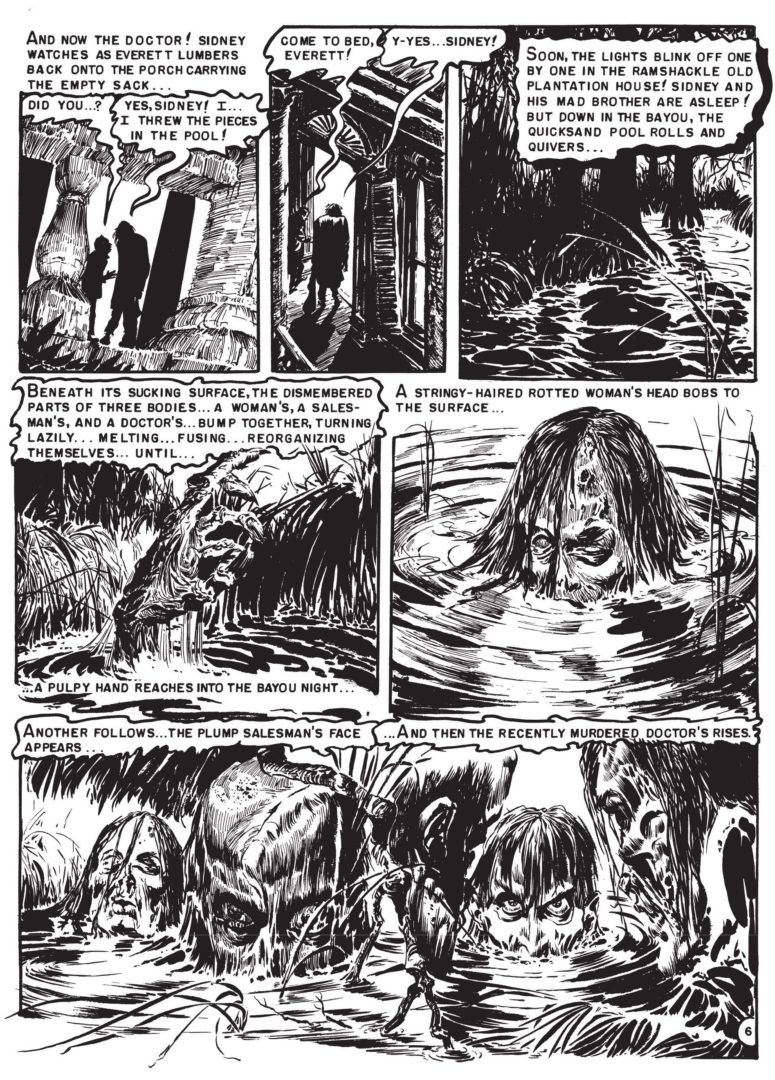

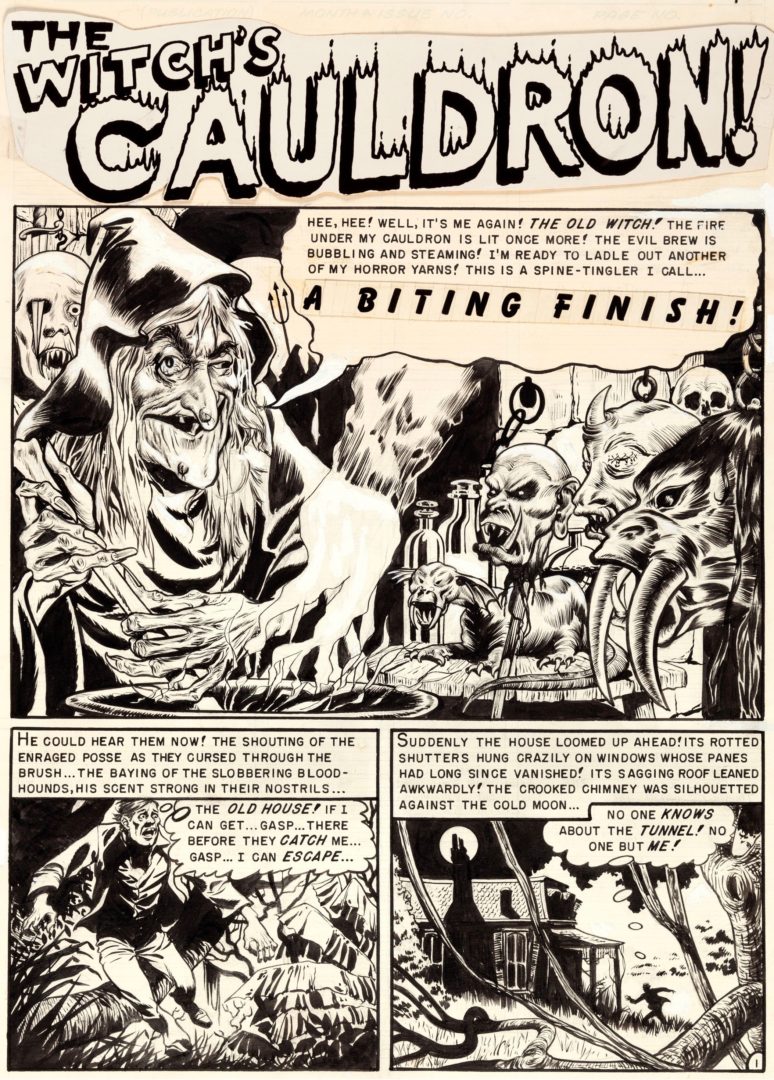

Considering how easily we want to believe that there surely must be something wrong with any writer or artist who voluntarily wanders into a valley of darkness, it isn“t that surprising really that we want to accept a similar narrative of a wretched life where arguably the greatest illustrator of horror comics is concerned. Fans and readers who“ve seen Graham Ingels“ work from the time when he was the artistic force behind comic book titles such as The Haunt of Fear from publisher EC Comics, will have no trouble to recall a specific style that seemed to have so much as dripped from the four-colored newsprint paper: The nauseating spectacle of fleshy body parts either melting before our very eyes or being grafted onto each other in a perverse, ill-shapen way as a result of some haphazardly performed surgical procedure, or the sharp teeth of rodents gnawing away at vital organs while their human prey was very much alive. Make no mistake, once EC Comics had stumbled onto horror comics as one of the major new trends in comic books in the early 1950s, there were horror comic stories a  dime a dozen. Still, many artists came into this field who had talent to spare. Some of which remained nameless or are forgotten, others who went on to become some of the finest creators in the industry, like Gene Colan for example. Yet the art created by Graham Ingels is so unique and in our mind so closely connected to his person, that he stands head and shoulder not only above his contemporaries in the horror genre within comics, but some may argue, among every horror artist. It is no coincidence that the winner for best horror art at the EC Fan-Addict Convention in 1972 was the tale “Horror We? How“s Bayou?”“ (which also could have easily won the prize for the best pun in a story title had such an award been given out). This gruesome tale is what sums up Ingels“ work just perfectly. What we see from one panel to the next is so horrific that it seems impossible that the artist manages to increase the level of nastiness even further until we arrive at the most disgusting twist ending, but still he does. This was a horror master, if not the horror master on top of his game. Ingels“ work has become so seminal in the horror genre that even those readers who have yet to read their first comic from EC that features one of his yarns, are familiar with it. Artists like Bernie Wrightson, a master of the horror genre himself, name Ingels as their main source of influence and not only is it easy to see why, it shows in their work. Even when horror comics fell out of favor, an artist of such high caliber like Gene Colan, who went on to become one of the major creative voices at Marvel Comics and the field of superhero comics in the 1960s, couldn“t quite shake the shadow Ingels had cast over the more than a decade younger fellow artist. Ingels work is there in the despair that noble heroes such as Daredevil or Iron Man would show on occasion, something that made Marvel Comics so unique in its infancy, and there is the darkness and the grotesque that Ingels is widely associated with in Prince Namor and his undersea kingdom. And not only this, but Gene“s beautiful female characters owe a large debt to the master of the macabre as well, going by his earlier work. According to their own words, he not only was a major influence on other comic book artists, but on filmmakers and writers such as John Carpenter, George A. Romero and Stephen King. Knowing this and looking at his work during his horror period at EC Comics, and mostly since Ingels was able to conjure up such visceral terrors with just pencil and ink in hand (made the more gruesome by the expertly handled color work of Marie Severin), would we not just as easily accept any type of legend about the artist that feeds into the kind of narrative we have already constructed in our minds? There is the idea of the artist as an antisocial loner, a man who wouldn“t hesitate to curse out his fellow men during any chance encounter on the street not unlike Poe had in those falsified biographical notices. And of course, in the 1950s version of the creator on drugs, alcohol and cannabis had taken the place of opium and hashish. Indeed, there is the legend that Ingels became a drunk once the Comics Code of America put an end to horror comics. That he was unable to secure any new work in the comic book industry because he and his former employer EC Comics were so closely linked to the depravities which had brought about a self-regulatory body in the first place. He was effectively blacklisted by every other publisher and it all went downhill from there. As an outright alcoholic by that time, the same legend has it that Graham Ingels died alone in the basement of a church that housed a homeless shelter and a soup kitchen. Broken in body and spirit that his beloved, albeit so very bizarre source of creativity had been taken from him. Surely, would such a tale not make sense in light of the work Ingels had produced during what seems his most fruitful period? However, as likely as all of this sounds, this narrative is as incorrect as the one Rufus Wilmot Griswold constructed about the life of his late rival Edgar Allan Poe. And very much unlike with the careers of Tod Browning or Michael Powell, Ingels was not shunned by the industry once the horror game was up. In fact, the master artist found it easy to transition into other genres once the Comics Code Authority was founded in 1954, the governing body set up by the industry itself to placate national sentiment. As for his drug abuse, Ingels was indeed a heavy drinker. His neighbor and best friend, fellow artist George Evans would recall: “Old Graham, he“d keep the drinks coming and coming”¦ I“d try to knock off one while Graham would have finished two or three cans of beer”¦ and boy, what an effort to keep up!”“ But in a way, that was par for the course for many men (and women) in the 1950s when each living room came equipped with a bar. It was also something that was fairly widespread among many creatives and not unheard of at EC. Wally Wood, for example, was a heavy drinker as well, yet in his case, this only seemed to give credit to the image of pure machismo that has long since been built up around the latter artist. Wood tragically died by his own hand after a series of strokes, most likely caused by his alcoholism, made it nearly impossible for him to continue working. Ingels lived well into his mid-seventies. And he did not die in an old church. Reed Crandall, the other “old man”“ at EC Comics among many younger, up and coming artists, started drinking fairly late in life once his career was over, Ingels had been drinking from an early age on. It was not his art or the subject matters which he depicted that had driven him to the bottle, or the beer cans as it were. He wasn“t a loner, either. In fact, Ingels was married. He had a teenage daughter and a son.

dime a dozen. Still, many artists came into this field who had talent to spare. Some of which remained nameless or are forgotten, others who went on to become some of the finest creators in the industry, like Gene Colan for example. Yet the art created by Graham Ingels is so unique and in our mind so closely connected to his person, that he stands head and shoulder not only above his contemporaries in the horror genre within comics, but some may argue, among every horror artist. It is no coincidence that the winner for best horror art at the EC Fan-Addict Convention in 1972 was the tale “Horror We? How“s Bayou?”“ (which also could have easily won the prize for the best pun in a story title had such an award been given out). This gruesome tale is what sums up Ingels“ work just perfectly. What we see from one panel to the next is so horrific that it seems impossible that the artist manages to increase the level of nastiness even further until we arrive at the most disgusting twist ending, but still he does. This was a horror master, if not the horror master on top of his game. Ingels“ work has become so seminal in the horror genre that even those readers who have yet to read their first comic from EC that features one of his yarns, are familiar with it. Artists like Bernie Wrightson, a master of the horror genre himself, name Ingels as their main source of influence and not only is it easy to see why, it shows in their work. Even when horror comics fell out of favor, an artist of such high caliber like Gene Colan, who went on to become one of the major creative voices at Marvel Comics and the field of superhero comics in the 1960s, couldn“t quite shake the shadow Ingels had cast over the more than a decade younger fellow artist. Ingels work is there in the despair that noble heroes such as Daredevil or Iron Man would show on occasion, something that made Marvel Comics so unique in its infancy, and there is the darkness and the grotesque that Ingels is widely associated with in Prince Namor and his undersea kingdom. And not only this, but Gene“s beautiful female characters owe a large debt to the master of the macabre as well, going by his earlier work. According to their own words, he not only was a major influence on other comic book artists, but on filmmakers and writers such as John Carpenter, George A. Romero and Stephen King. Knowing this and looking at his work during his horror period at EC Comics, and mostly since Ingels was able to conjure up such visceral terrors with just pencil and ink in hand (made the more gruesome by the expertly handled color work of Marie Severin), would we not just as easily accept any type of legend about the artist that feeds into the kind of narrative we have already constructed in our minds? There is the idea of the artist as an antisocial loner, a man who wouldn“t hesitate to curse out his fellow men during any chance encounter on the street not unlike Poe had in those falsified biographical notices. And of course, in the 1950s version of the creator on drugs, alcohol and cannabis had taken the place of opium and hashish. Indeed, there is the legend that Ingels became a drunk once the Comics Code of America put an end to horror comics. That he was unable to secure any new work in the comic book industry because he and his former employer EC Comics were so closely linked to the depravities which had brought about a self-regulatory body in the first place. He was effectively blacklisted by every other publisher and it all went downhill from there. As an outright alcoholic by that time, the same legend has it that Graham Ingels died alone in the basement of a church that housed a homeless shelter and a soup kitchen. Broken in body and spirit that his beloved, albeit so very bizarre source of creativity had been taken from him. Surely, would such a tale not make sense in light of the work Ingels had produced during what seems his most fruitful period? However, as likely as all of this sounds, this narrative is as incorrect as the one Rufus Wilmot Griswold constructed about the life of his late rival Edgar Allan Poe. And very much unlike with the careers of Tod Browning or Michael Powell, Ingels was not shunned by the industry once the horror game was up. In fact, the master artist found it easy to transition into other genres once the Comics Code Authority was founded in 1954, the governing body set up by the industry itself to placate national sentiment. As for his drug abuse, Ingels was indeed a heavy drinker. His neighbor and best friend, fellow artist George Evans would recall: “Old Graham, he“d keep the drinks coming and coming”¦ I“d try to knock off one while Graham would have finished two or three cans of beer”¦ and boy, what an effort to keep up!”“ But in a way, that was par for the course for many men (and women) in the 1950s when each living room came equipped with a bar. It was also something that was fairly widespread among many creatives and not unheard of at EC. Wally Wood, for example, was a heavy drinker as well, yet in his case, this only seemed to give credit to the image of pure machismo that has long since been built up around the latter artist. Wood tragically died by his own hand after a series of strokes, most likely caused by his alcoholism, made it nearly impossible for him to continue working. Ingels lived well into his mid-seventies. And he did not die in an old church. Reed Crandall, the other “old man”“ at EC Comics among many younger, up and coming artists, started drinking fairly late in life once his career was over, Ingels had been drinking from an early age on. It was not his art or the subject matters which he depicted that had driven him to the bottle, or the beer cans as it were. He wasn“t a loner, either. In fact, Ingels was married. He had a teenage daughter and a son.

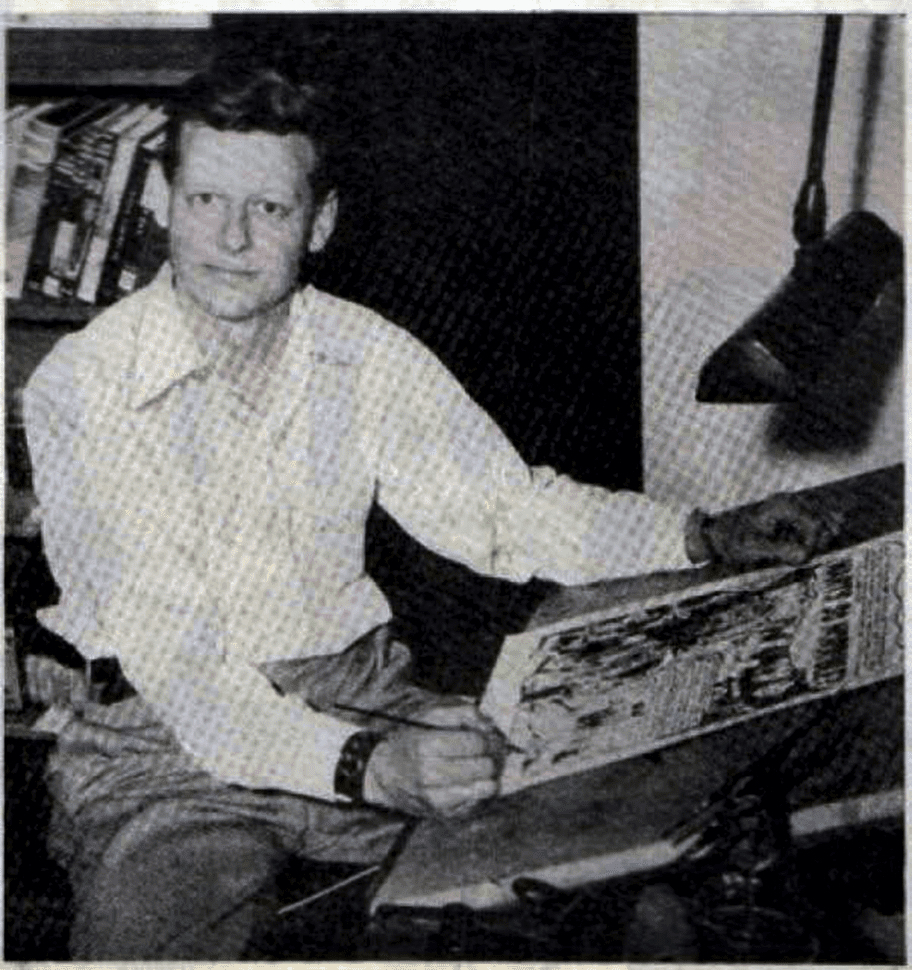

The artist who began signing his artwork as “Ghastly”“ on his publisher“s insistence in 1952, did not date his half-sister nor did he marry his underage cousin. Neither did he ever work for a circus or a sideshow. In the portrait EC Comics began to circulate as part of their “Artist of the Issue”“ feature in the early 50s, you see a man who looks totally normal. There“re no devil“s horns on his forehead, and he doesn“t have cloven hooves instead of feet. In his crisp white shirt, the guy with the sandy-brown Kennedy hair might very well work as a sales representative for IBM or a local car dealership. Though he looks a bit pudgy around the face, from too much booze you can suspect, this was the guy who created those terrors that kept kids awake at night, the man who would prove so influential and who would see beauty in ugliness. Born in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1915, Ingels had normal childhood, though at the age of fourteen, Ingels had an encounter with death. This was when his father died who was an artist. Since this happened around the time of the stock market crash, it was normal to see kids joining the workforce  for any kind of work that was available. He worked as a window washer and did other odd jobs. When he was sixteen, young Ingels decided to try his luck in his late father“s line of work and he soon began drawing theater displays. Though he was the oldest artist when he began to work for EC Comics soon after Gaines had inherited the fledgling company from his father, a comic pioneer who had co-founded All-American Comics, and he would remain the old man on EC“s art team, he was too young to have had a hand in the art for the direct predecessor of comic books, the pulp magazine when these cheaply and quickly produced thrills were at their most lurid and most sadistic. It was during the early days of the Great Depression that the pulps began to venture more deeply into the horrific, and by extension, into the well-nigh pornographic. With the double-punch of “Dracula”“ and “Frankenstein”“ making big bank at the box office, despite cash being in short supply, publisher of pulp magazines pounced on this new trend and commissioned covers that shrewdly combined the aesthetic of Browning“s “Freaks”“ with the damsel in distress motif. In these hand-painted miniature billboards that easily rivaled any movie poster art, readers soon saw busty girls in ripped clothes with their garters and stockings exposed, debutantes and ingenues in high heel shoes and chains that were menaced by dwarfs with long whips or some variation of a freakish monster. These tableaux of titillating depravity were the forte of artists like John Newton Howitt and Norman Saunders. Then there was Hugh Joseph Ward who pushed the aspects of sadism even a bit further while adding a racist bent to the proceedings with the aggressors being foreign looking men, who came with an exotic, swarthy complexion, and an obvious and very threatening male potency and their unchecked sex drive. Interestingly though, the only woman who worked among these highly talented male artists, Margaret Brundage, did offer more nudity, but she also saw much beauty in the exotic and foreign. Books with a cover by Brundage sold tremendously, which quickly lead to some rivalry from surprising places. Author L. Sprague de Camp not only outed Brundage as a woman (something which was widely and wisely kept secret by her editors), reason enough for a scandal, but de Camp also implied that she had her underage daughters pose for the well-nigh nude young women in her cover paintings. Brundage had no children. This came at a time when books with names like Spicy Detective and Spicy-Adventure Stories began to cause a stir, but not in the way publishers intended. The “Spicy”“ moniker was very much a signifier that readers could expect near pornographic content in such pamphlets. Politicians, sensing that this offered a platform they could run on, promised to force the pulps to clean up their act. Local legislation passed that either forbade the sale of these books to minors or asked retailers to put them into brown bags. It was this environment that Graham Ingels entered into when he was twenty. Meanwhile he had studied at the Hawthorne School of Art in New York, but he was still a beginner. Since he lacked the experience and seemingly the talent these much more accomplished cover artists had, he was relegated to working on the interior art. These were mostly roughly drawn sketches that accompanied each story. Done only in pencil and ink versus the fully painted covers, less time and funds were used on such ink drawings. It was simply cost prohibitive to be spending too much money on these art commissions, though they did prove a nice training ground for talented artists like Jack Kirby and Graham Ingels, who got married the same year to his fiancée Gertrude. Two years later, the couples“ daughter Deanna was born, which put additional pressure on the aspiring artist who was getting nowhere, really. It is interesting to speculate what might have happened had he entered into the world of pulp magazines just one year earlier when horror pulps like Terror Tales were all the rage, but it is safe to say that there would have been no way for him to compete with John Newton Howitt, the king of horror covers. And it seems a fair assessment that Ingels, who as a freelancer rather spent time working on illustrations for slicker magazines outside the world of pulps whenever he could land any such assignment, was not good enough. It is also of note that many artists who did interior art soon either jumped with both feet into the developing market of comics like Jack Kirby did, who was incredibly fast or simply made this space their own domain like Virgil Finlay who created some breathtaking interior artwork. With the horror pulps having run their course, readers and publishers alike once again embraced the science fiction genre, which still awarded plenty of liberties to show glamorous women in skimpy attire, albeit in a much healthier, cleaner environment.

for any kind of work that was available. He worked as a window washer and did other odd jobs. When he was sixteen, young Ingels decided to try his luck in his late father“s line of work and he soon began drawing theater displays. Though he was the oldest artist when he began to work for EC Comics soon after Gaines had inherited the fledgling company from his father, a comic pioneer who had co-founded All-American Comics, and he would remain the old man on EC“s art team, he was too young to have had a hand in the art for the direct predecessor of comic books, the pulp magazine when these cheaply and quickly produced thrills were at their most lurid and most sadistic. It was during the early days of the Great Depression that the pulps began to venture more deeply into the horrific, and by extension, into the well-nigh pornographic. With the double-punch of “Dracula”“ and “Frankenstein”“ making big bank at the box office, despite cash being in short supply, publisher of pulp magazines pounced on this new trend and commissioned covers that shrewdly combined the aesthetic of Browning“s “Freaks”“ with the damsel in distress motif. In these hand-painted miniature billboards that easily rivaled any movie poster art, readers soon saw busty girls in ripped clothes with their garters and stockings exposed, debutantes and ingenues in high heel shoes and chains that were menaced by dwarfs with long whips or some variation of a freakish monster. These tableaux of titillating depravity were the forte of artists like John Newton Howitt and Norman Saunders. Then there was Hugh Joseph Ward who pushed the aspects of sadism even a bit further while adding a racist bent to the proceedings with the aggressors being foreign looking men, who came with an exotic, swarthy complexion, and an obvious and very threatening male potency and their unchecked sex drive. Interestingly though, the only woman who worked among these highly talented male artists, Margaret Brundage, did offer more nudity, but she also saw much beauty in the exotic and foreign. Books with a cover by Brundage sold tremendously, which quickly lead to some rivalry from surprising places. Author L. Sprague de Camp not only outed Brundage as a woman (something which was widely and wisely kept secret by her editors), reason enough for a scandal, but de Camp also implied that she had her underage daughters pose for the well-nigh nude young women in her cover paintings. Brundage had no children. This came at a time when books with names like Spicy Detective and Spicy-Adventure Stories began to cause a stir, but not in the way publishers intended. The “Spicy”“ moniker was very much a signifier that readers could expect near pornographic content in such pamphlets. Politicians, sensing that this offered a platform they could run on, promised to force the pulps to clean up their act. Local legislation passed that either forbade the sale of these books to minors or asked retailers to put them into brown bags. It was this environment that Graham Ingels entered into when he was twenty. Meanwhile he had studied at the Hawthorne School of Art in New York, but he was still a beginner. Since he lacked the experience and seemingly the talent these much more accomplished cover artists had, he was relegated to working on the interior art. These were mostly roughly drawn sketches that accompanied each story. Done only in pencil and ink versus the fully painted covers, less time and funds were used on such ink drawings. It was simply cost prohibitive to be spending too much money on these art commissions, though they did prove a nice training ground for talented artists like Jack Kirby and Graham Ingels, who got married the same year to his fiancée Gertrude. Two years later, the couples“ daughter Deanna was born, which put additional pressure on the aspiring artist who was getting nowhere, really. It is interesting to speculate what might have happened had he entered into the world of pulp magazines just one year earlier when horror pulps like Terror Tales were all the rage, but it is safe to say that there would have been no way for him to compete with John Newton Howitt, the king of horror covers. And it seems a fair assessment that Ingels, who as a freelancer rather spent time working on illustrations for slicker magazines outside the world of pulps whenever he could land any such assignment, was not good enough. It is also of note that many artists who did interior art soon either jumped with both feet into the developing market of comics like Jack Kirby did, who was incredibly fast or simply made this space their own domain like Virgil Finlay who created some breathtaking interior artwork. With the horror pulps having run their course, readers and publishers alike once again embraced the science fiction genre, which still awarded plenty of liberties to show glamorous women in skimpy attire, albeit in a much healthier, cleaner environment.

With this trend on the horizon, Fiction House, one of the biggest players in the pulp magazine business, began putting out a brand-new science fiction magazine called Planet Stories near the end of 1939. In the same year, the publisher had already done a dry run when in their first new publication for the year Jungle Stories, they also featured some stories which came with science fiction themes. Planet Stories“ new editor in chief Malcolm Reiss started to cast about for scifi writers and competent artists. With bills to pay, Ingels about had it as a freelancer. Not unlike when Edgar Allen Poe had run into money issues, the artist joined the armed forces. Though, as luck would have it, Graham Ingels“ artistic talent wasn“t simply discovered by his superiors at the U.S. Navy, but appreciated. He was commissioned to paint a mural for the United Nations. Even when he was assigned to a battleship in 1943, the order was quickly reversed, and he was  instead stationed in Long Island to work on illustrations for instruction manuals. With newfound appreciation for his artistic endeavors, and more self-confidence and experience under his belt, and such a close proximity to Manhattan, he darkened the door of Malcom Reiss, who quickly hired him for interior art for Planet Stories, Jungle Stories and other pulp publications. Allowing Graham to sign his work with G. Ingels all the while Ingels was still serving in the Navy. Meanwhile, though, other work opportunities had begun to develop at Fiction House which would pull Ingels into a new direction. Sensing that pulps were trouble and losing steam and that comic books were on the rise, Fiction House had created a line of comic books not unlike what Martin Goodman and Harry Donenfeld had done, but for much simpler reasons. The founders of the companies that one day would become Marvel Comics and DC Comics respectively (Donenfeld had helped his business partner Jack Liebowitz and Max Gaines to establish another comic book company which would be absorbed into DC as well), were forced into this safer line of publishing when the censors had begun to crack down on their more lurid pulp books. Only a year after Malcolm Reiss had set up Jungle Stories and Planet Stories, Fiction House got Planet Comics under way. This was by no means their first comic book. Jumbo Comics actually pre-dated Jungle Stories by a year, but once the pulp magazine took off, the publisher quickly converted it from a cartoon book into a jungle adventure anthology which soon came with a new star attraction: Sheena, the Jungle Queen. Though the book initially featured some science fiction stories and tales of the supernatural, it was the long-legged blonde in her animal fur bikini who took over the lead-in story and the covers. This prompted the publisher to set up another jungle themed title in 1940, Jungle Comics. Though ostensibly this anthology comic featured a male jungle hero like Jungle Stories did, Kaänga and Ki-Gor respectively, in the comic series the hero“s love interest, beautiful, raven-haired Ann Mason wasn“t so much a damsel in distress, but a highly capable heroine in her own right, much like Sheena herself. Though there would be many superheroines soon, like Black Cat, Black Venus, Phantom Lady and many more, Fiction House had stumbled onto a new trend. If the women either shared top-billing with the hero or where the star of a title, girl readers were on board in a way female readers had never been with the pulps which were geared at a slightly more mature audience one which was mostly made up of young guys. Planet Comics had its own fair share of gorgeous female adventurers like Gale Allen and her Girl Squadron, Futura and Mysta of the Moon. Though the cover artwork would not necessarily let this on, these covers were very much in the tradition of what Allen Anderson and Earle Bergey“s pulp magazine covers looked like, with their handsome space explorers and exotic, glamorous women from other planets, girl readers found a lot to like in these female heroines, which outlasted most of their superheroine counterparts. And boys surely did not mind these gorgeous ladies who came in futuristic, albeit skimpy outfits and high-heeled boots that made the most of their long, naked legs. Planet Comics, which was initially a sixty-nine pages thick extravaganza (ads excluded) and which ran from 1940 to 1953, had just started a new serial in No. 21. “The Lost World”“ was created by one of the house writers (which included pulp veterans like Frank Belknap Long and Walter B. Gibson, the writer of The Shadow series) using the house-name Thorncliffe Herrick, and Rudy Palais, though the artist was assigned to cover work and other interior art and would only stay for the debut issue to set things into motion, with future comics legend Nick Cardy taking over for the next issue and yet another artist doing the third. However, what was presented to readers with issue No. 21 (1942), did not look like much at first. On the splash panel we met Hunt Bowman, a rugged, muscular archer who has a run in with some aliens and who then gets whisked away to an alien planet. And of course, there was a gorgeous blonde woman. All of this felt very much like it had come right out Edgar Rice Burroughs“ playbook. Another tale about an alpha male leaving Earth behind to show aliens on a distant world how superior and noble Earthmen were. And the titular “Lost World”“ may well could have been intended as a stand-in for Barsoom. Indeed, the blonde girl, who was a captive like Bowman, was Lyssa, Queen of the Lost World. But there was one twist. The world Hunt was forced to leave behind was not one of high civilization or that of America during the Civil War. Hunt“s world was that of Earth of thirty-third century and it was a desolate place. During a war of the planets, many centuries ago, our home planet had been conquered by the alien race called the Voltamen which in turn had rendered all development at a stage that felt very mid-twentieth century, with vegetation and wildlife growing wild. So much so, that Hunt believe himself the last man on Earth. To signify the diminished role humans now played, with the ravaged skyline of a Chicago in total ruins used as a backdrop at the beginning, the first proper panel showed a rat which bared its jagged teeth. When Graham Ingels was offered the strip, he didn“t have much enthusiasm for it. Working for comics felt like a step down, since these four-colored pamphlets were considered second-tier stuff when compared to the pulps that had real writers working on them like Cornell Woolrich, Gardner Fox, Ray Bradbury and Leigh Brackett (one of the few woman in the industry, Brackett who would go on to a career as a Hollywood screenwriter), but he needed the cash. To his relieve, Ingels discovered that the writer had closed issue No. 23 with a workable premise.