“WALLY WOOD’S MEN“ A COLUMN ABOUT EC COMICS, PART 2

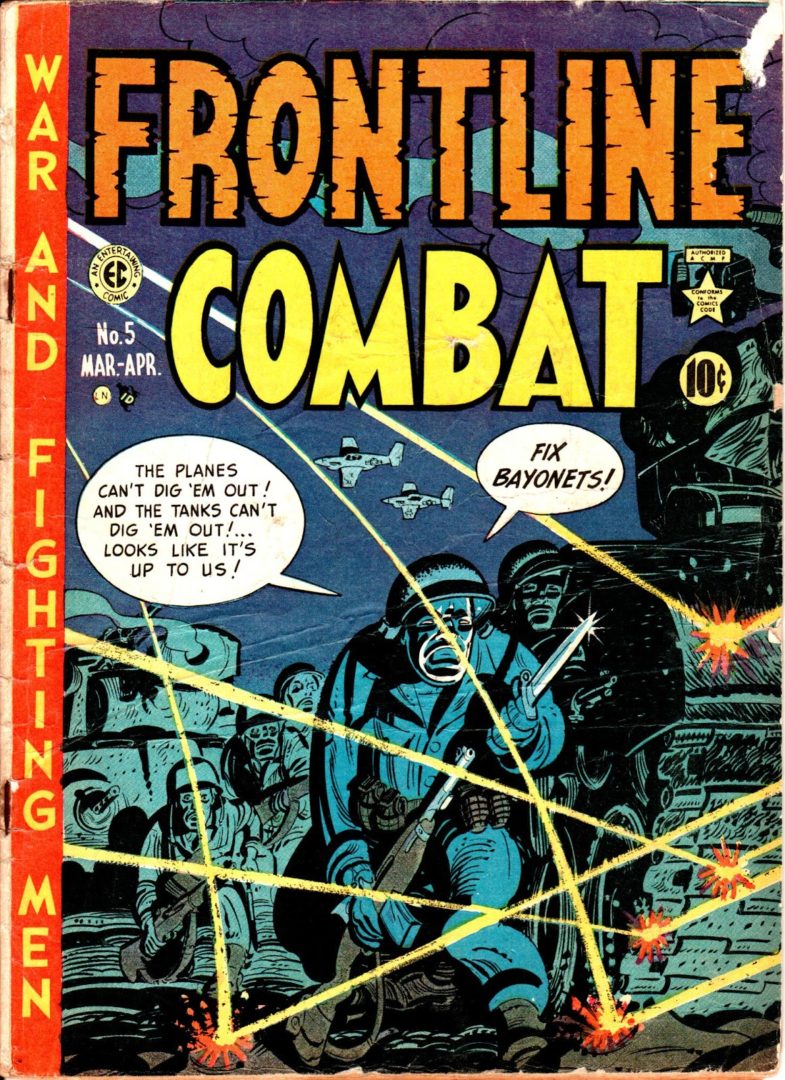

What does a real man look like? And how does a real man act? If you asked this question in the early 1950’s, you only needed to take a look at the most bankable Hollywood stars. In 1951, Humphrey Bogart had a hit movie. And so, had John Wayne. Bogart was a bit past his prime, and having hit his early fifties, in “African Queen”“, he was well beyond portraying a cool private eye who never seemed to take off his hat or his trench coat. Instead he was cast as a curmudgeon. But his rough-and-ready, somewhat greasy Charlie Allnut, a mechanic who piloted an old steamboat, was still charming to boot. What man his age would not be able to identify with such a cantankerous guy who ultimately had a heart of gold and who even let Kathrine Hepburn“s character Rose navigate the boat while he took care of the engine, knowing full well that she was in over her head. John Wayne, nearly a decade younger, was in full hero mode. If you wanted to cast a stoic cowboy or a commanding officer during war times who did not mince words, the Duke knew how to deliver. If you preferred the quiet gentleman-type, impossibly handsome actor Gregory Peck fit the bill. And audiences clearly agreed, since Peck had not one, but three massive hits at the box office for that year. And if you were a girl and you wanted to dream about a type of guy you could introduce your parents to, there was Montgomery Clift who burnt up the silver screen with a new type of acting style when romancing a stunningly beautiful Elizabeth Taylor. She wouldn“t take her violet eyes off his pretty face that emoted all the sensitivity a girl could ever want in a guy who had this unique presence that told you that he would care for you. But if you wanted a pure alpha male, there was only one man who was the entire package, in more ways than one, a guy who made the other guys look old, and Clift, who was just four years younger, look a bit effete by comparison. A guy needed to be able to rock a white t-shirt, but a real man needed to be of sinew and muscle, of raw, assured masculinity. His manliness very much oozed out from every pore while he moved like a jungle cat, fast, fierce and with a sense of danger and purpose, that such a man wouldn“t only garner respect, but that other man, who were lesser men by default, either wanted to be his friend or they feared him. And in 1951 there was only one actor who could scream the words “I“m the King Around Here!”“ while only seconds prior he“d been licking dinner off his fingers like some prehistoric hunter who was seated at an open fire and who had slain the beast that had served as this evening“s supper all by himself. As for Hollywood, there was only one actor who made it all work and who made it look easy, and most of all, made it look real. And in a sense, it was real. It was as real as the young war veteran who put this type of man on paper when he gave a visual representation to the perfect romantic hero in a science fiction tale, and when he gave a face to those men who did not run, but moved forward on Omaha Beach or when defending the 38th parallel. Like Marlon Brando, who took what was true on the inside, genuine emotion that came from experience, and put it on the outside, master artist Wallace Wood externalized romanticized ideals and likewise the horrors of war onto the page which lay before him. He did it while drawing characters like Sergeant Purvis who made men out of grunts during basic training and molded them into the right kind of material for the 805th Parachute Infantry Regiment, so that these young recruits were not only well-versed in the art of killing enemy troops, but had the mettle to keep going when the going got tough. It is not difficult to be a hero when things are easy, but those under Sergeant Purvis purview had a specific task. With allied troops moving in from the Atlantic to storm the Cherbourg Peninsula, the paratroopers needed to provide crucial support behind the lines in occupied France. Like the actor, Wood took what were emotions that were rooted in real-life observations for his art. Like many able-bodied men, Wally had enlisted, and he“d served his country first in the Merchant Marine and then, in the U.S. Paratroops. Even later, the war years stayed with him. There is a photograph of him from 1980 which shows him as one hell of a defiant guy. A smoke tugged into one corner of his mouth, he wears an army jacket that is adorned with a few pin-badge buttons and a service patch. His gray hair is cut short, his skin is leathery, and he brandishes a replica of Thompson semi-automatic submachine gun. Of course, Sergeant Purvis was a fictional character. Purvis lived in the pages of a story that appeared in a comic book series called Two-Fisted Tales, in issue No. 20 to be exact, published early in 1951. This series had just started a few months earlier, and oddly enough with issue No. 18, though it wasn“t anything special that a comic book series would have its start not with a No. 1 for its first issue in the 50s, especially not with this publisher. EC Comics, which originally had stood for Educational Comics, then, with a small handful of books only, for the much more marketing-friendly Entertaining Comics, was now fully in the entertaining business. Due to this and ever-changing trends and reader appetites, a series might get re-named after just a few issues. However this was only half of the story with Two-Fisted Tales which came out when publisher Bill Gaines and his editor Al Feldstein were still finding their feet, after Gaines had inherited the comic book company from his late father Max. Due to some miscommunications with wholesalers, Bill Gaines had received word that his new series The Haunt of Fear was a bust. He and Feldstein had just banked the fortunes of the fledgling company on a new emerging trend, horror comics. It was another attempt of theirs at creating a successful anthology horror comic series, after Tales from the Crypt. Competitor Avon had put out a horror one-shot to test the demand, and American Comics Group had been able to establish a full-fledged series centered around the supernatural and the macabre with Adventures Into The Unknown as early as 1948. The Haunt of Fear had taken its numbering from a Western Comic and before that, a Funny Book. In order to provide his new title, Two-Fisted Tales, with a pedigree by making it appear as if this new offering was an already established series, Gaines decided to use the numbering from the cancelled The Haunt of Fear series. If this was not confusing enough, imagine Gaines“ surprise when he found out that the horror book was indeed selling. Thus, Bill uncancelled this series after he“d already printed the first issue of the other title, and both titles came out with a No. 18 issue, Two-Fisted Combat as its very first issue, The Haunt of Fear as just another book, without readers noticing a thing. The idea for this new series that offered a world of conflict in which men took center stage (even though female characters did appear, but far less than in the other new titles), came from an artist who“d joined the company in the previous year. His name was Harvey Kurtzman. As for his motivation, Kurtzman had this to say: “Nobody had done anything on the depressing aspects of war”¦ logic led me to research actual war and tell kids what was true about war.”“ While it is next to impossible to say if kids read these issues initially or if their older brothers and their fathers bought them, men who had experienced war, Kurtzman and EC Comics had a hit on their hands. Right at the same time when the fifth issue of Two-Fisted Tale hit newsstand, there was a second war title from EC Comics, also under the stewardship of Kurtzman who not only wrote every story but provided his artists with complete layouts. If you consider the lead-time on a comic book, the production on the first issue of Frontline Combat had to have started right around the time the sales number from the second issue of the first series made it back to Gaines. Even more astonishing is the fact that writer-artist-editor Kurtzman still found the time to start a third comic series near the end of the next year, this time a humor and satire book called MAD. To say that Harvey was on a roll is most certainly an understatement. Though Kurtzman was incredibly gifted as an artist himself, with a very unique style, not only did time constraints make it prohibitive for him to pencil and ink every one of the four stories per issue himself, he was also savvy enough to realize that certain stories required the talents of different artists whose own styles fitted perfectly to what type of tale he had in mind at any given time. Like Al Feldstein on every other book EC put out, and later Johnny Craig on The Vault of Horror, Harvey was like a showrunner on a modern television (or streaming) series. He set the direction, communicated his vision and hand-picked a director for each episode. Though he had a number of highly accomplished artists working on his war titles, chief among them Jack Davis or John Severin, arguably, to this day Wally Wood remains the one artist mostly associated with these war tales.

What does a real man look like? And how does a real man act? If you asked this question in the early 1950’s, you only needed to take a look at the most bankable Hollywood stars. In 1951, Humphrey Bogart had a hit movie. And so, had John Wayne. Bogart was a bit past his prime, and having hit his early fifties, in “African Queen”“, he was well beyond portraying a cool private eye who never seemed to take off his hat or his trench coat. Instead he was cast as a curmudgeon. But his rough-and-ready, somewhat greasy Charlie Allnut, a mechanic who piloted an old steamboat, was still charming to boot. What man his age would not be able to identify with such a cantankerous guy who ultimately had a heart of gold and who even let Kathrine Hepburn“s character Rose navigate the boat while he took care of the engine, knowing full well that she was in over her head. John Wayne, nearly a decade younger, was in full hero mode. If you wanted to cast a stoic cowboy or a commanding officer during war times who did not mince words, the Duke knew how to deliver. If you preferred the quiet gentleman-type, impossibly handsome actor Gregory Peck fit the bill. And audiences clearly agreed, since Peck had not one, but three massive hits at the box office for that year. And if you were a girl and you wanted to dream about a type of guy you could introduce your parents to, there was Montgomery Clift who burnt up the silver screen with a new type of acting style when romancing a stunningly beautiful Elizabeth Taylor. She wouldn“t take her violet eyes off his pretty face that emoted all the sensitivity a girl could ever want in a guy who had this unique presence that told you that he would care for you. But if you wanted a pure alpha male, there was only one man who was the entire package, in more ways than one, a guy who made the other guys look old, and Clift, who was just four years younger, look a bit effete by comparison. A guy needed to be able to rock a white t-shirt, but a real man needed to be of sinew and muscle, of raw, assured masculinity. His manliness very much oozed out from every pore while he moved like a jungle cat, fast, fierce and with a sense of danger and purpose, that such a man wouldn“t only garner respect, but that other man, who were lesser men by default, either wanted to be his friend or they feared him. And in 1951 there was only one actor who could scream the words “I“m the King Around Here!”“ while only seconds prior he“d been licking dinner off his fingers like some prehistoric hunter who was seated at an open fire and who had slain the beast that had served as this evening“s supper all by himself. As for Hollywood, there was only one actor who made it all work and who made it look easy, and most of all, made it look real. And in a sense, it was real. It was as real as the young war veteran who put this type of man on paper when he gave a visual representation to the perfect romantic hero in a science fiction tale, and when he gave a face to those men who did not run, but moved forward on Omaha Beach or when defending the 38th parallel. Like Marlon Brando, who took what was true on the inside, genuine emotion that came from experience, and put it on the outside, master artist Wallace Wood externalized romanticized ideals and likewise the horrors of war onto the page which lay before him. He did it while drawing characters like Sergeant Purvis who made men out of grunts during basic training and molded them into the right kind of material for the 805th Parachute Infantry Regiment, so that these young recruits were not only well-versed in the art of killing enemy troops, but had the mettle to keep going when the going got tough. It is not difficult to be a hero when things are easy, but those under Sergeant Purvis purview had a specific task. With allied troops moving in from the Atlantic to storm the Cherbourg Peninsula, the paratroopers needed to provide crucial support behind the lines in occupied France. Like the actor, Wood took what were emotions that were rooted in real-life observations for his art. Like many able-bodied men, Wally had enlisted, and he“d served his country first in the Merchant Marine and then, in the U.S. Paratroops. Even later, the war years stayed with him. There is a photograph of him from 1980 which shows him as one hell of a defiant guy. A smoke tugged into one corner of his mouth, he wears an army jacket that is adorned with a few pin-badge buttons and a service patch. His gray hair is cut short, his skin is leathery, and he brandishes a replica of Thompson semi-automatic submachine gun. Of course, Sergeant Purvis was a fictional character. Purvis lived in the pages of a story that appeared in a comic book series called Two-Fisted Tales, in issue No. 20 to be exact, published early in 1951. This series had just started a few months earlier, and oddly enough with issue No. 18, though it wasn“t anything special that a comic book series would have its start not with a No. 1 for its first issue in the 50s, especially not with this publisher. EC Comics, which originally had stood for Educational Comics, then, with a small handful of books only, for the much more marketing-friendly Entertaining Comics, was now fully in the entertaining business. Due to this and ever-changing trends and reader appetites, a series might get re-named after just a few issues. However this was only half of the story with Two-Fisted Tales which came out when publisher Bill Gaines and his editor Al Feldstein were still finding their feet, after Gaines had inherited the comic book company from his late father Max. Due to some miscommunications with wholesalers, Bill Gaines had received word that his new series The Haunt of Fear was a bust. He and Feldstein had just banked the fortunes of the fledgling company on a new emerging trend, horror comics. It was another attempt of theirs at creating a successful anthology horror comic series, after Tales from the Crypt. Competitor Avon had put out a horror one-shot to test the demand, and American Comics Group had been able to establish a full-fledged series centered around the supernatural and the macabre with Adventures Into The Unknown as early as 1948. The Haunt of Fear had taken its numbering from a Western Comic and before that, a Funny Book. In order to provide his new title, Two-Fisted Tales, with a pedigree by making it appear as if this new offering was an already established series, Gaines decided to use the numbering from the cancelled The Haunt of Fear series. If this was not confusing enough, imagine Gaines“ surprise when he found out that the horror book was indeed selling. Thus, Bill uncancelled this series after he“d already printed the first issue of the other title, and both titles came out with a No. 18 issue, Two-Fisted Combat as its very first issue, The Haunt of Fear as just another book, without readers noticing a thing. The idea for this new series that offered a world of conflict in which men took center stage (even though female characters did appear, but far less than in the other new titles), came from an artist who“d joined the company in the previous year. His name was Harvey Kurtzman. As for his motivation, Kurtzman had this to say: “Nobody had done anything on the depressing aspects of war”¦ logic led me to research actual war and tell kids what was true about war.”“ While it is next to impossible to say if kids read these issues initially or if their older brothers and their fathers bought them, men who had experienced war, Kurtzman and EC Comics had a hit on their hands. Right at the same time when the fifth issue of Two-Fisted Tale hit newsstand, there was a second war title from EC Comics, also under the stewardship of Kurtzman who not only wrote every story but provided his artists with complete layouts. If you consider the lead-time on a comic book, the production on the first issue of Frontline Combat had to have started right around the time the sales number from the second issue of the first series made it back to Gaines. Even more astonishing is the fact that writer-artist-editor Kurtzman still found the time to start a third comic series near the end of the next year, this time a humor and satire book called MAD. To say that Harvey was on a roll is most certainly an understatement. Though Kurtzman was incredibly gifted as an artist himself, with a very unique style, not only did time constraints make it prohibitive for him to pencil and ink every one of the four stories per issue himself, he was also savvy enough to realize that certain stories required the talents of different artists whose own styles fitted perfectly to what type of tale he had in mind at any given time. Like Al Feldstein on every other book EC put out, and later Johnny Craig on The Vault of Horror, Harvey was like a showrunner on a modern television (or streaming) series. He set the direction, communicated his vision and hand-picked a director for each episode. Though he had a number of highly accomplished artists working on his war titles, chief among them Jack Davis or John Severin, arguably, to this day Wally Wood remains the one artist mostly associated with these war tales.

In Wally Wood, the man who had “come to open the purple testament of bleeding war”“ at EC Comics, found his perfect collaborator where men were concerned who always looked their heroic best. But, as we can gather from statements he made about him, Kurtzman considered Wally a hero in his own right. Kurtzman would use words like “Intensity”“ and “self-sacrifice”“ when describing how Wood would tackle his scripts, words that immediately conjure up images of combat and acts of selfless heroism. You can almost smell the rounds fired from an automatic rifle, taste the blood and sweat in your mouth as your lips are burning from heat, thirst and the tobacco from filter-less cigarettes. Indeed, Wood had clawed his way into the comics industry. Before he enlisted when he was still underage,  Wood had already had many jobs under his belt. He worked the odd job during the nightshift at a factory, he was a busboy as well as a pin boy in a bowling alley, cleaning tables and setting up the bowling pins. He moonlighted as truck loader and as dental lab assistant. And like his father, he did a stint as a lumberjack. Upon getting his discharge from the Army, he enrolled for a semester at the Minneapolis School of art in 1947. Once he had moved to New York City, he likewise attended a semester at the Burne Hogarth“s Cartoonist and Illustrators School on the G.I. Bill in 1948. Unable to get any art assignments with comic publisher, even though there was always a high demand for any guy who could hold a pencil in the right way, it was the self-proclaimed “King of Comics”“ Victor Fox, a progenitor of highly salacious material, who hired Wood via an agent named Rinaldo Epworth. Not convinced of the young man“s artistic skills though, all Wally got to do was to work as a letterer on whatever romance comics Victor was peddling in a given months. Though he was eventually upgraded to doing fill-in work for backgrounds, Wood finally lucked out when he met fellow artist John Severin who introduced him to comics“ legend Will Eisner who had him work on backgrounds as well, but for his massively successful newspaper feature The Spirit. It was Victor Fox however, who let Wood do this first pencil and ink comic story in Women Outlaws No. 7 in 1949. With some industry contacts of his own now, Wood got together with Harry Harrison, Joe Orlando and Sidney Check to share a studio in the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Wood worked and studied other artists, also those who moved in and out of their studio like Al Williamson and Roy Krenkel. In a way, this was already almost half of Bill Gaines bullpen from the early 1950s, but Wood was not there yet. He had to cut some dead weight loose first. He and Harrison had formed a duo, and this was how they presented themselves to Gaines who was in the market for new talent. Harrison, who many years later would hit it big as a science fiction novelist, was a talker. He did the pencils while Wally was once again relegated to doing backgrounds and inks. But it was then, that Wood spent night after night at the drawing board to study and re-draw the works of men like Joe Kubert and Frank Frazetta, the latter who was a prodigy. Legend had it that when Frazetta“s mother had brought her son to a teacher at a prestigious art school, the teacher had taken one look at the boy“s portfolio only to attest that there was nothing he would be able to teach him that young Frank not already did better. Frazetta was six years old. He was no Frank, but it quickly dawned on Wood that he was selling himself short. He and Harrison got to do a werewolf story in the very first issue of The Vault of Horror. In fact, it was No. 12 from April 1950. Gaines had just decided to discontinue Crime Patrol. And like he had rebranded Gunfighter into The Haunt of Fear, from now on, the covers for this erstwhile imitation of Lev Gleason“s Crime Does No Pay, would let every kid know right away that this was no longer a series about cops and robbers, but more of that creepy stuff their mothers didn“t want them to read. Though “The Werewolf Legend”“ from a script by Gardner Fox and Harrison calls for some moody scenes and Harrison and Wood deliver, it is a serviceable product at best, and at worst it has Wood adhering so closely to Harrison“s uninspired pencils that the visuals suffer for it. He knew he could do better. Wood knew that he needed a collaborator who better meshed with his own sensibilities, to improve his style, gain confidence and ultimately become an artist with a unique voice. It was unavoidable it seems that he and Harrison would have a bitter falling out in the same year.

Wood had already had many jobs under his belt. He worked the odd job during the nightshift at a factory, he was a busboy as well as a pin boy in a bowling alley, cleaning tables and setting up the bowling pins. He moonlighted as truck loader and as dental lab assistant. And like his father, he did a stint as a lumberjack. Upon getting his discharge from the Army, he enrolled for a semester at the Minneapolis School of art in 1947. Once he had moved to New York City, he likewise attended a semester at the Burne Hogarth“s Cartoonist and Illustrators School on the G.I. Bill in 1948. Unable to get any art assignments with comic publisher, even though there was always a high demand for any guy who could hold a pencil in the right way, it was the self-proclaimed “King of Comics”“ Victor Fox, a progenitor of highly salacious material, who hired Wood via an agent named Rinaldo Epworth. Not convinced of the young man“s artistic skills though, all Wally got to do was to work as a letterer on whatever romance comics Victor was peddling in a given months. Though he was eventually upgraded to doing fill-in work for backgrounds, Wood finally lucked out when he met fellow artist John Severin who introduced him to comics“ legend Will Eisner who had him work on backgrounds as well, but for his massively successful newspaper feature The Spirit. It was Victor Fox however, who let Wood do this first pencil and ink comic story in Women Outlaws No. 7 in 1949. With some industry contacts of his own now, Wood got together with Harry Harrison, Joe Orlando and Sidney Check to share a studio in the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Wood worked and studied other artists, also those who moved in and out of their studio like Al Williamson and Roy Krenkel. In a way, this was already almost half of Bill Gaines bullpen from the early 1950s, but Wood was not there yet. He had to cut some dead weight loose first. He and Harrison had formed a duo, and this was how they presented themselves to Gaines who was in the market for new talent. Harrison, who many years later would hit it big as a science fiction novelist, was a talker. He did the pencils while Wally was once again relegated to doing backgrounds and inks. But it was then, that Wood spent night after night at the drawing board to study and re-draw the works of men like Joe Kubert and Frank Frazetta, the latter who was a prodigy. Legend had it that when Frazetta“s mother had brought her son to a teacher at a prestigious art school, the teacher had taken one look at the boy“s portfolio only to attest that there was nothing he would be able to teach him that young Frank not already did better. Frazetta was six years old. He was no Frank, but it quickly dawned on Wood that he was selling himself short. He and Harrison got to do a werewolf story in the very first issue of The Vault of Horror. In fact, it was No. 12 from April 1950. Gaines had just decided to discontinue Crime Patrol. And like he had rebranded Gunfighter into The Haunt of Fear, from now on, the covers for this erstwhile imitation of Lev Gleason“s Crime Does No Pay, would let every kid know right away that this was no longer a series about cops and robbers, but more of that creepy stuff their mothers didn“t want them to read. Though “The Werewolf Legend”“ from a script by Gardner Fox and Harrison calls for some moody scenes and Harrison and Wood deliver, it is a serviceable product at best, and at worst it has Wood adhering so closely to Harrison“s uninspired pencils that the visuals suffer for it. He knew he could do better. Wood knew that he needed a collaborator who better meshed with his own sensibilities, to improve his style, gain confidence and ultimately become an artist with a unique voice. It was unavoidable it seems that he and Harrison would have a bitter falling out in the same year.

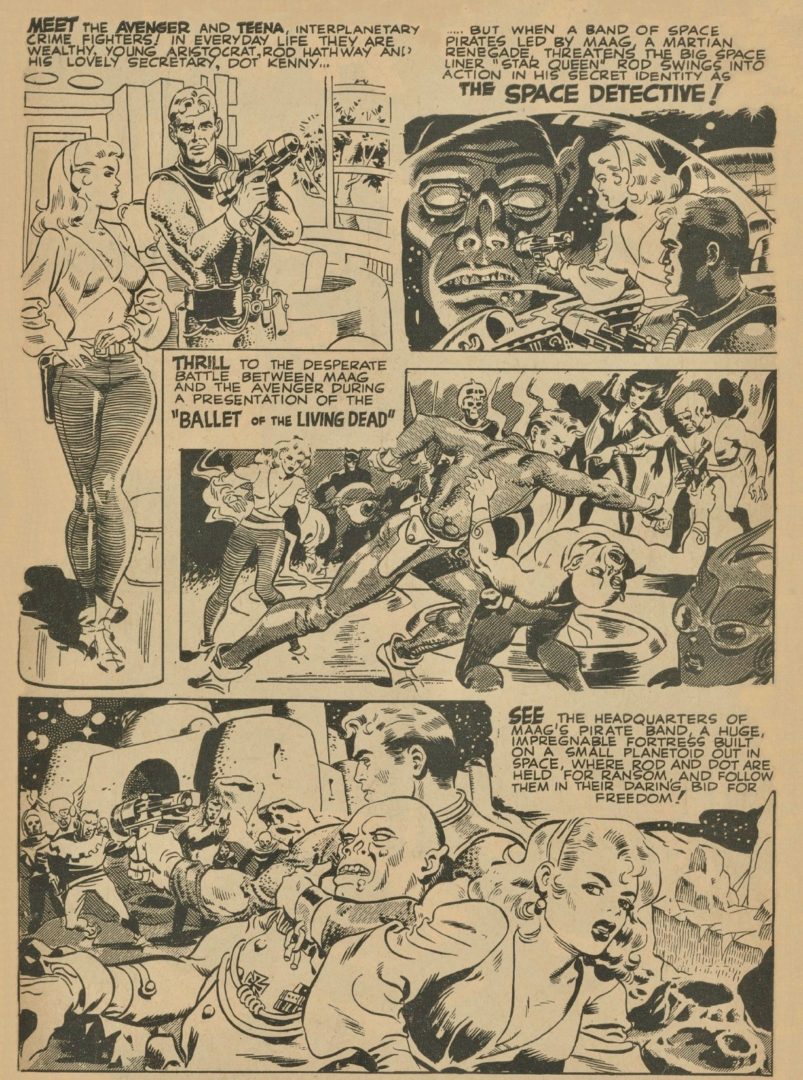

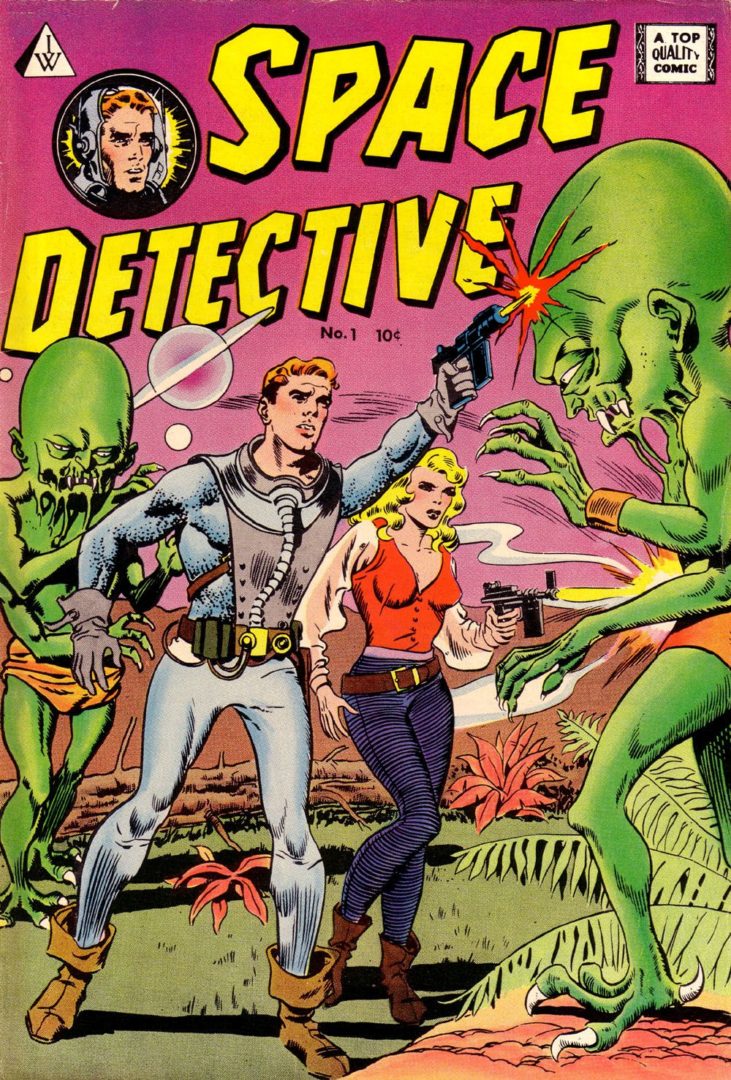

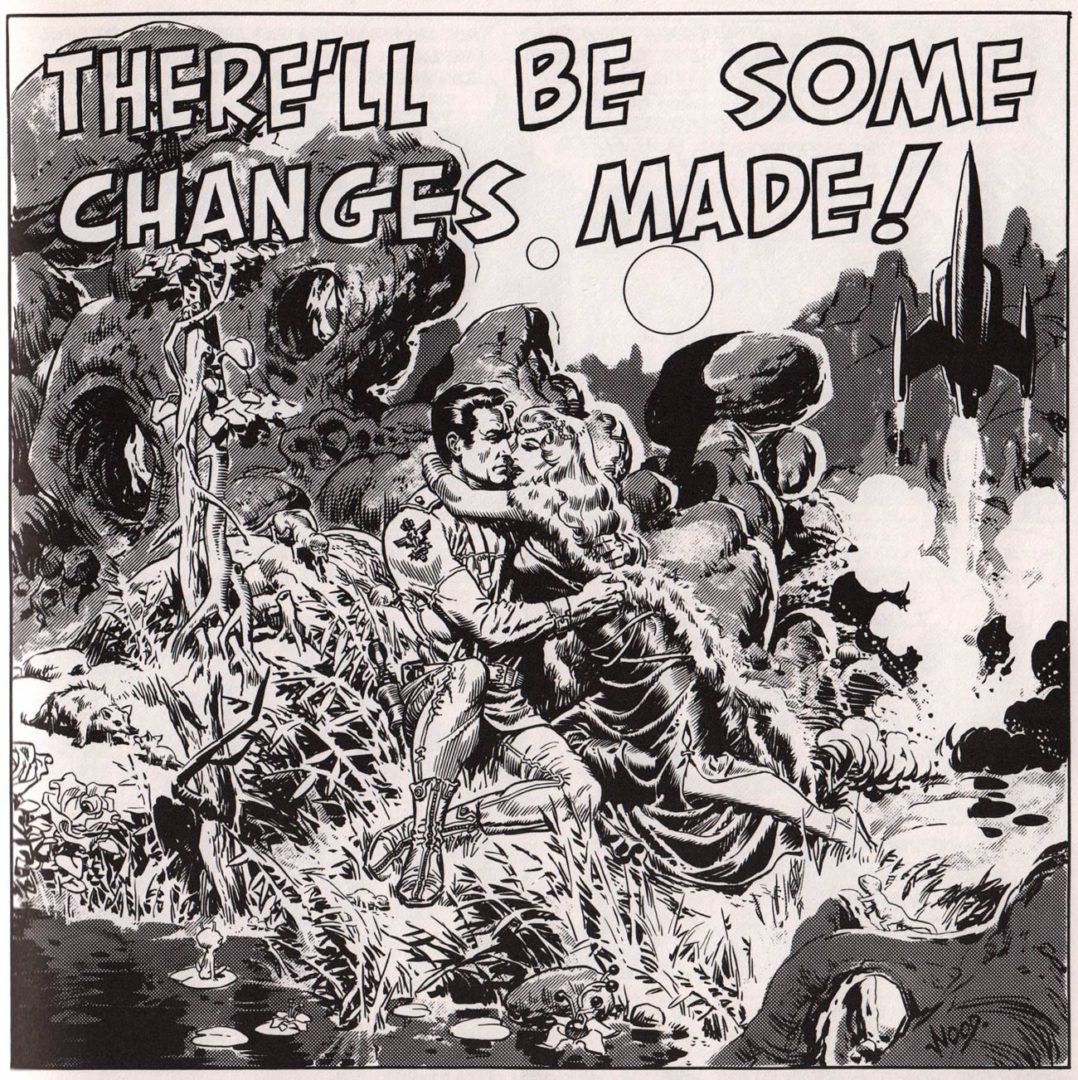

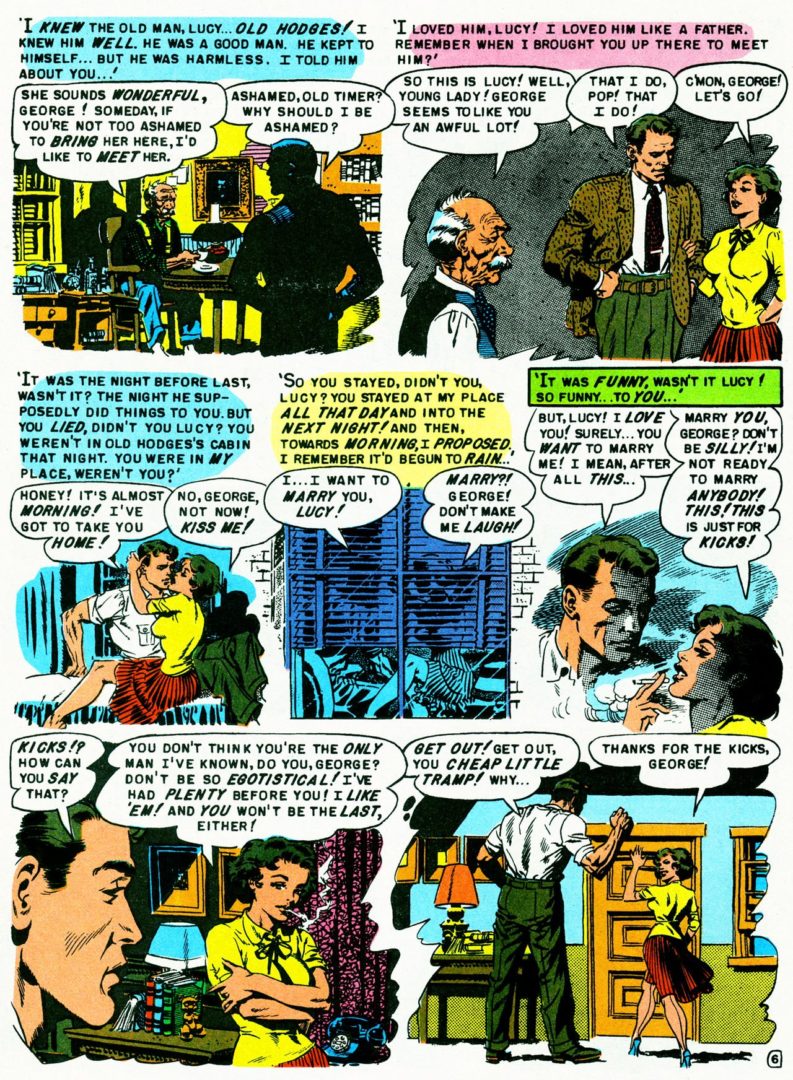

Like many people will, once they“ve untangled themselves from a loop-sided relationship, Wood began playing the field, meaning in his case that he was working for other publishers while he hooked up with a new partner who was already in the picture while his team-up with Harrison still lasted. His name was Joe Orlando, and while Joe and Wood eventually became two of the artists who are widely associated with EC Comics and what Gaines and his editor Al Feldstein cleverly marketed as a “New Trend”“, Wood and Orlando launched a short-lived science fiction book for Avon at the end of 1951 which would clearly betray their respective growth as visual storytellers and as master craftsmen. And once they were fully ensconced at EC in 1952, the artists only went from strength to strength, further building on what they had learned from each other while each of them was developing his own voice. Looking at the opening page which introduced readers to the attractive main characters, this multi-panel black and white page offers further testament to Wood“s artistic progress once he had cut Harry Harrison loose. Though it is unknown who wrote the captions on the opening page, these already create lots of excitement just on their own in the minds of young readers: “Meet The Avenger and Teena. Interplanetary crime fighters! In everyday life they are wealthy young aristocrat, Rod Hathway and his lovely secretary, Dot Keey, but when a band of space pirates led by Maag, a Martian renegade, threatens the big space”¦ Rod swings into action in his secret identity as  The Space Detective!”“ Now, Rod was one of those handsome, blonde and mostly dull heroes one found in other books, only much better rendered, but Teena was unlike any female character readers had seen before. Though being cast in a subservient role, that of a secretary, and with the balance of power further tipped in Rod“s favor due to his station in life, the full figure shot of the young blonde offered by Orlando and Wood, with her head turned in profile while her body faced front, told a different story. Teena had a most confident look on her pretty face that made her seem a bit aloof while at the same time her eyes rested less on the hero but on the blaster, he cocked with one hand, a ray-gun which came with an unusually thick barrel. Wearing an Alice band that held her perfect hair back, Teena sported tight leggings and a top that simultaneously revealed much of her ample bust while it also left her midriff including her navel bare. The message must have been quite puzzling to any younger reader while older kids instinctively got what was going on. Teena was not impressed by Rod“s money or his social standing, or his fairly standard good looks. What interested her was if he was able to deliver the goods, so speak. Anyway, things had become much more complicated than in one of EC“s war titles. And the sexually charged imagery only grew in intensity from panel to panel as the two artists offered sneak peaks of what readers could expect from the issue, namely more of this strangely exciting stuff. And so, it was. Interestingly, Wood and Orlando and writer Walter Gibson (most famous for being the main writer of The Shadow pulp series in the 1930s and 1940s), delivered something that was fairly unusual for this time: the artists and the writer supplied not one, but three tales just in the debut issue. Though the quality of the art is not consistent throughout these three tales and not even from page to page, these were not yet fully-formed artists and the lead time must surely have played a role with such a high page count comparatively speaking, all the hallmarks of the pairs later work is on display. Heroes, beautiful women in either nigh impractical outfits or exotic attire, which made the most of their highly sexualized bodies, and scientific looking machinery that gave the impression that it could actually work. But unlike what was to come in many of his later stories across different genres for EC Comics, mainly in the tales that came from ideas by Gaines and a script by Feldstein (written on the art board), Rod and Teena had a balanced, collaborative if platonic relationship. She was his secretary in name only. Though the artists supplied not more than the cover and the black and white teaser page for the following issue, this carried through. With reversed roles (Wood provided the pencils for what little the pair contributed to the follow-up issue, with Orlando inking), the cover showed The Avenger and an even more attractive Teena as they were going up against some gigantic aliens. Instead of recoiling with raw terror from the green-hued creatures like many of her contemporaries were wont to do on the covers of similar titles, the young blonde packed a blaster of her own, and she was not afraid to unleash its deadly yellow rays with lethal force. And once readers turned to the preview page, similar images emerged. Teena packed some serious heat when she and the blonde aristocrat turned space hero fought renegade robots and gorgeous Bat-Women with leathery wings who were clad in skintight, black catsuits. There was even a panel in which the pair was auctioned off as slaves with Teena and the blonde hero nearly nude and in heavy chains. The Space Detective was ripped with muscles and one could assume, and with just a piece of cloth covering up his private parts, that the name Rod seemed aptly chosen. This is an amazing page in that it also offers a look into the future in more ways than one. Starting in 1971, Wood would produce a black and white comic strip which appeared every week for two and a half years in Overseas Weekly, a publication that was only available at a PAX of a military installation abroad. With Wood“s CANNON, troops who were stationed around the globe saw a visual continuation of this kind of material, but this time with a more mature and political bent. As for The Space Detective, the series got cancelled just a few months later. Once readers had seen what Wood and Orlando could do, it wasn“t the same without them. Interestingly, Teena quickly fell into the role of a damsel in distress once they had left the series. But all of this gender equality happened under the guise of a science fiction narrative, meaning that any bold attempts at gender equality were ways off, something that may come true only in a distant future. Wally stayed on with EC Comics, and other than working on a few horror and crime stories and later on the “preachies”“ in Shock SuspenStories, outside of his science fiction work, which he and Harrison had convinced Gaines to do in the first place, he left his mark on those war stories Harvey Kurtzman wrote, and those tales were looking towards the past, to the Roman Empire, the Battle of Agincourt, the Civil War of the 1860s, and of course, The Second World War. Though Kurtzman most certainly did not shy away from also doing stories about the then still ongoing Korean War, maybe some of his best material, this still happened with a distinct voice of the past. He was a storyteller, not a journalist, but a historian.

The Space Detective!”“ Now, Rod was one of those handsome, blonde and mostly dull heroes one found in other books, only much better rendered, but Teena was unlike any female character readers had seen before. Though being cast in a subservient role, that of a secretary, and with the balance of power further tipped in Rod“s favor due to his station in life, the full figure shot of the young blonde offered by Orlando and Wood, with her head turned in profile while her body faced front, told a different story. Teena had a most confident look on her pretty face that made her seem a bit aloof while at the same time her eyes rested less on the hero but on the blaster, he cocked with one hand, a ray-gun which came with an unusually thick barrel. Wearing an Alice band that held her perfect hair back, Teena sported tight leggings and a top that simultaneously revealed much of her ample bust while it also left her midriff including her navel bare. The message must have been quite puzzling to any younger reader while older kids instinctively got what was going on. Teena was not impressed by Rod“s money or his social standing, or his fairly standard good looks. What interested her was if he was able to deliver the goods, so speak. Anyway, things had become much more complicated than in one of EC“s war titles. And the sexually charged imagery only grew in intensity from panel to panel as the two artists offered sneak peaks of what readers could expect from the issue, namely more of this strangely exciting stuff. And so, it was. Interestingly, Wood and Orlando and writer Walter Gibson (most famous for being the main writer of The Shadow pulp series in the 1930s and 1940s), delivered something that was fairly unusual for this time: the artists and the writer supplied not one, but three tales just in the debut issue. Though the quality of the art is not consistent throughout these three tales and not even from page to page, these were not yet fully-formed artists and the lead time must surely have played a role with such a high page count comparatively speaking, all the hallmarks of the pairs later work is on display. Heroes, beautiful women in either nigh impractical outfits or exotic attire, which made the most of their highly sexualized bodies, and scientific looking machinery that gave the impression that it could actually work. But unlike what was to come in many of his later stories across different genres for EC Comics, mainly in the tales that came from ideas by Gaines and a script by Feldstein (written on the art board), Rod and Teena had a balanced, collaborative if platonic relationship. She was his secretary in name only. Though the artists supplied not more than the cover and the black and white teaser page for the following issue, this carried through. With reversed roles (Wood provided the pencils for what little the pair contributed to the follow-up issue, with Orlando inking), the cover showed The Avenger and an even more attractive Teena as they were going up against some gigantic aliens. Instead of recoiling with raw terror from the green-hued creatures like many of her contemporaries were wont to do on the covers of similar titles, the young blonde packed a blaster of her own, and she was not afraid to unleash its deadly yellow rays with lethal force. And once readers turned to the preview page, similar images emerged. Teena packed some serious heat when she and the blonde aristocrat turned space hero fought renegade robots and gorgeous Bat-Women with leathery wings who were clad in skintight, black catsuits. There was even a panel in which the pair was auctioned off as slaves with Teena and the blonde hero nearly nude and in heavy chains. The Space Detective was ripped with muscles and one could assume, and with just a piece of cloth covering up his private parts, that the name Rod seemed aptly chosen. This is an amazing page in that it also offers a look into the future in more ways than one. Starting in 1971, Wood would produce a black and white comic strip which appeared every week for two and a half years in Overseas Weekly, a publication that was only available at a PAX of a military installation abroad. With Wood“s CANNON, troops who were stationed around the globe saw a visual continuation of this kind of material, but this time with a more mature and political bent. As for The Space Detective, the series got cancelled just a few months later. Once readers had seen what Wood and Orlando could do, it wasn“t the same without them. Interestingly, Teena quickly fell into the role of a damsel in distress once they had left the series. But all of this gender equality happened under the guise of a science fiction narrative, meaning that any bold attempts at gender equality were ways off, something that may come true only in a distant future. Wally stayed on with EC Comics, and other than working on a few horror and crime stories and later on the “preachies”“ in Shock SuspenStories, outside of his science fiction work, which he and Harrison had convinced Gaines to do in the first place, he left his mark on those war stories Harvey Kurtzman wrote, and those tales were looking towards the past, to the Roman Empire, the Battle of Agincourt, the Civil War of the 1860s, and of course, The Second World War. Though Kurtzman most certainly did not shy away from also doing stories about the then still ongoing Korean War, maybe some of his best material, this still happened with a distinct voice of the past. He was a storyteller, not a journalist, but a historian.

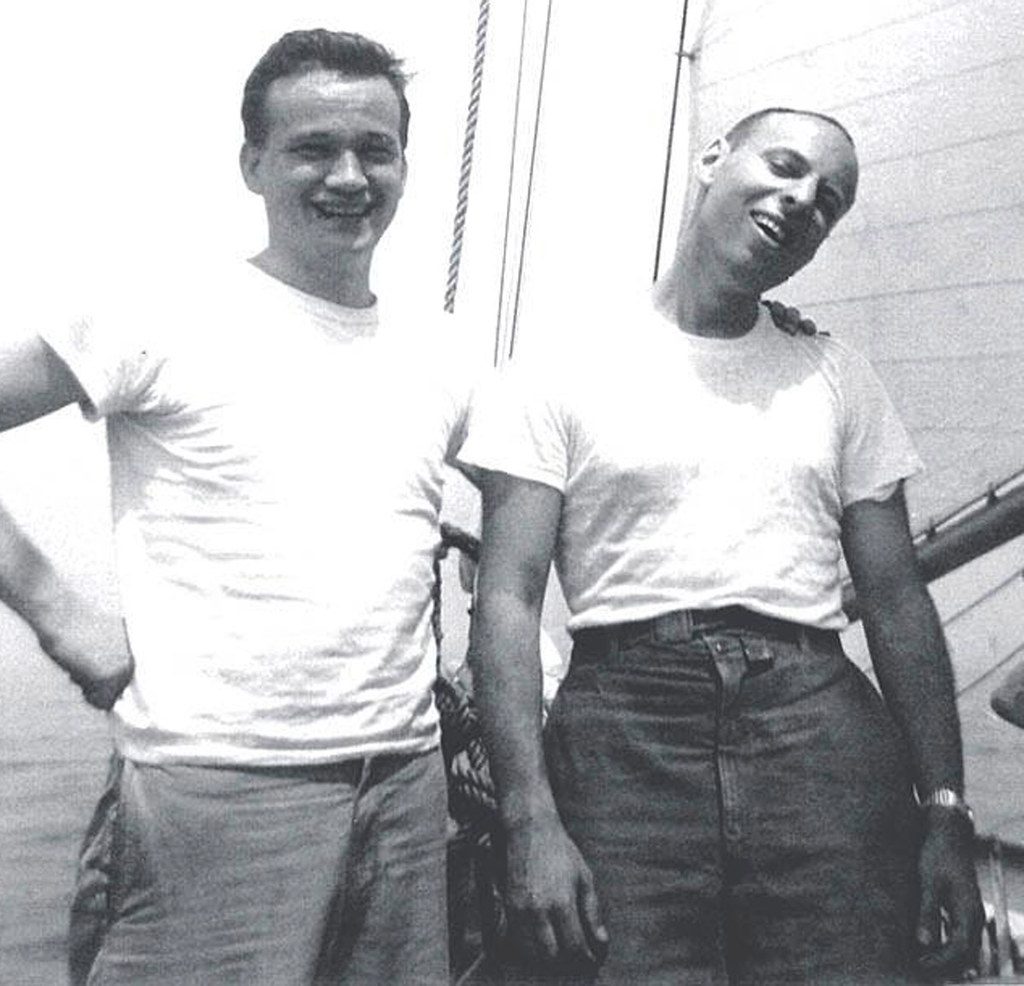

But what about Kurtzman himself? What type of man was the creator and showrunner of these books? If you were a boy reading these books or perhaps even an enlisted man, it seems highly likely that what came to mind was the image of a man who was stoic and confident in nature, who spoke little and only if had something profound to say. A man who would take care of business without talking about it with so many words. In short, a man who acted and most of all who  looked like those men rendered by Wally Wood. And if you knew just a few details about Harvey, they only seemed to confirm this mental image some readers may very well had formed in their heads. Three years older than Wood, Harvey served in the military as well during the war. And when he was discharged, not only had he been able to sell some of the cartoons he did to a number of publishers, but when he saw a pretty girl who worked as proof-reader for one of those places, he had no problem to sweep her off her feet, and she quickly agreed to marry him. The couple had a daughter now, Meredith, and they lived in uptown Manhattan. And when he did not work on his two books for Gaines, he had some cool hobbies, too. Photography, not a nerdy thing if you considered the men from Magnum like Frank Capra who went where the action was. Harvey also liked to work on his car. With that, you certainly imagined a guy who drove to a cabin in the woods on weekends, who hunted and fished and took pictures of nature and wildlife, maybe of a grizzly even. A guy who knew how to grow a beard and who wore a flannel shirt before that was cool. A guy who could handle himself far away from any civilization. In short, a guy who looked like the protagonist of a story Wally Wood was to illustrate for Shock SuspenStories called “Came The Dawn!”“ But had you come to 225 Lafayette Street in New York, the home of EC Comics, not only would you have learned that Bill Gaines had spent more time in the Army than Harvey had, in fact the publisher served for four years in the Army Air Corps, but you would have most likely walked past Harvey at the elevator banks. Here was a thin guy with the face of a horse and a receding hairline, and in his gray suit you had simply mistaken him for an insurance salesman. Most certainly not what Wood“s heroes looked like, or a real man“s man who hung with the guys and was good at manly stuff and at getting the girl he wanted. Kurtzman looked like a nerd who was destined to remain in the friend zone. Well, in that respect, Harvey had scored. But what about his military record and his first-hand experience of men in combat situations? EC published a short artist bio on an infrequent basis. Those one-pagers, which came with a black and white picture, appeared on the reverse side of a cover from a series the respective artist was associated with the most. The one for Kurtzman reads like whoever wrote the piece, was throwing a little shade at him where his military service and his manliness were concerned: “When the war came, Harvey went”¦ into the army, that is! He was in the Engineers in Louisiana, the Infantry in Texas, and the Artillery in North Carolina. He also worked on training aids for the Information-Education Division in North Carolina.”“ Other than many of his male contemporaries including Wally Wood, Kurtzman had not enlisted, but he got drafted. And he was never sent overseas. Wood, on the other hand, did not only volunteer, but he managed to do so when he was underage. But that was late in 1944, and while Wally Wood served in the Merchant Marine and he was on tours to the Philippines, Guam, South America and Italy, he was not involved in any combat situations. Wood switched to the U.S. Army eventually, to become paratrooper with the 11th Airborne Division, but he did so once the war had ended. Wood, who was born in the same year as Steve Ditko, was too young for a more active role, with half of his time of service spent in a defeated country that was now occupied by allied forces. In Ditko“s case Germany, and in Wood“s case, Hokkaido, a small island in the South Pacific which belonged to Japan. And that picture of him holding that replica of a tommy gun like a boss? That was a gesture of defiance and a big FU to the world and the industry in which he had worked for many years. By then he was experiencing vision problems in his left eye. He had suffered a number of small strokes and as far as his career went, he had left comics behind. In fact, in 1978, after moving from New York to Connecticut and then to Los Angeles, California, he had released a self-financed record album called “Wally Wood Sings”“. When his kidneys began to fail as consequence of many years of heavy drinking and from spending endless hours at the drawing table, he could not go on with having to face the prospect of dialysis and needing a transplant, which might not be granted to him in the foreseeable future due to his alcoholism. On Halloween night of 1981, at the relatively young age of fifty-four, Wally Wood killed himself by gunshot. And though he was not a war hero, he was not only a hero of the comic book industry, but he left one hell of a legacy behind, during a career in which he“d also helped to pioneer independent comics with his magazine Witzend. But his art influenced many other artists as well, artists who were kids when they saw his work for the very first time either during the time when it was published, or in one of the numerous reprints of the EC titles and his other works.

looked like those men rendered by Wally Wood. And if you knew just a few details about Harvey, they only seemed to confirm this mental image some readers may very well had formed in their heads. Three years older than Wood, Harvey served in the military as well during the war. And when he was discharged, not only had he been able to sell some of the cartoons he did to a number of publishers, but when he saw a pretty girl who worked as proof-reader for one of those places, he had no problem to sweep her off her feet, and she quickly agreed to marry him. The couple had a daughter now, Meredith, and they lived in uptown Manhattan. And when he did not work on his two books for Gaines, he had some cool hobbies, too. Photography, not a nerdy thing if you considered the men from Magnum like Frank Capra who went where the action was. Harvey also liked to work on his car. With that, you certainly imagined a guy who drove to a cabin in the woods on weekends, who hunted and fished and took pictures of nature and wildlife, maybe of a grizzly even. A guy who knew how to grow a beard and who wore a flannel shirt before that was cool. A guy who could handle himself far away from any civilization. In short, a guy who looked like the protagonist of a story Wally Wood was to illustrate for Shock SuspenStories called “Came The Dawn!”“ But had you come to 225 Lafayette Street in New York, the home of EC Comics, not only would you have learned that Bill Gaines had spent more time in the Army than Harvey had, in fact the publisher served for four years in the Army Air Corps, but you would have most likely walked past Harvey at the elevator banks. Here was a thin guy with the face of a horse and a receding hairline, and in his gray suit you had simply mistaken him for an insurance salesman. Most certainly not what Wood“s heroes looked like, or a real man“s man who hung with the guys and was good at manly stuff and at getting the girl he wanted. Kurtzman looked like a nerd who was destined to remain in the friend zone. Well, in that respect, Harvey had scored. But what about his military record and his first-hand experience of men in combat situations? EC published a short artist bio on an infrequent basis. Those one-pagers, which came with a black and white picture, appeared on the reverse side of a cover from a series the respective artist was associated with the most. The one for Kurtzman reads like whoever wrote the piece, was throwing a little shade at him where his military service and his manliness were concerned: “When the war came, Harvey went”¦ into the army, that is! He was in the Engineers in Louisiana, the Infantry in Texas, and the Artillery in North Carolina. He also worked on training aids for the Information-Education Division in North Carolina.”“ Other than many of his male contemporaries including Wally Wood, Kurtzman had not enlisted, but he got drafted. And he was never sent overseas. Wood, on the other hand, did not only volunteer, but he managed to do so when he was underage. But that was late in 1944, and while Wally Wood served in the Merchant Marine and he was on tours to the Philippines, Guam, South America and Italy, he was not involved in any combat situations. Wood switched to the U.S. Army eventually, to become paratrooper with the 11th Airborne Division, but he did so once the war had ended. Wood, who was born in the same year as Steve Ditko, was too young for a more active role, with half of his time of service spent in a defeated country that was now occupied by allied forces. In Ditko“s case Germany, and in Wood“s case, Hokkaido, a small island in the South Pacific which belonged to Japan. And that picture of him holding that replica of a tommy gun like a boss? That was a gesture of defiance and a big FU to the world and the industry in which he had worked for many years. By then he was experiencing vision problems in his left eye. He had suffered a number of small strokes and as far as his career went, he had left comics behind. In fact, in 1978, after moving from New York to Connecticut and then to Los Angeles, California, he had released a self-financed record album called “Wally Wood Sings”“. When his kidneys began to fail as consequence of many years of heavy drinking and from spending endless hours at the drawing table, he could not go on with having to face the prospect of dialysis and needing a transplant, which might not be granted to him in the foreseeable future due to his alcoholism. On Halloween night of 1981, at the relatively young age of fifty-four, Wally Wood killed himself by gunshot. And though he was not a war hero, he was not only a hero of the comic book industry, but he left one hell of a legacy behind, during a career in which he“d also helped to pioneer independent comics with his magazine Witzend. But his art influenced many other artists as well, artists who were kids when they saw his work for the very first time either during the time when it was published, or in one of the numerous reprints of the EC titles and his other works.

They did not belong to those troops who stormed the beaches in Normandy, men of the ground infantry of the Army who had bullets from German machine guns flying at them. And they weren“t among those marines who knew how to handle a flamethrower and who used this equipment of terror to singe jungle vegetation, enemy material and flesh alike. But still, the stories Kurtzman and Wood created together were real, and in no small part this had a lot to do with how different the men were from each other in how they approached their subjects. When Kurtzman had said that he wanted to do war tales, for him this meant that he would  painstakingly gather all the information he needed for a particular story, and then shape the narrative in a way that brought the essence to the forefront. Whereas Brando used raw, genuine and comparable experiences and emotions to build his characters from the insight out, like he was taught by his teacher Stella Adler, Harvey Kurtzman started with the external. He was a researcher. When Kurtzman crafted a story involving the Merchant Marine based on Wood“s suggestion, he did not press Wood for any specifics, instead he went ahead and wrote a story about an event Wood had heard a lot of stories about. This was not something Wally had lived through, and Kurtzman could have written about something that Wood did experience instead, but it never occurred to him. This was not the kind of realism Kurtzman was going for. These were no first-hand accounts or tale tales passed around by a group of veterans after many years had passed in an attempt to make sense of it all, to find meaning in the meaningless, in the random and the cruel. The early 50s were also a time when men who had been in combat situations, didn“t like to share their experiences with outsiders. This was also a time when a man could not admit to having been afraid. This was a time of a silent generation of men, some of which would find it hard to interact with their spouse or their kids. But when Wood, and also Kurtzman as an artist, put words into drawings that would go with the captions and the dialogue, something happened. If you were one of those who mistook Harvey Kurtzman for an insurance salesman, you were certainly surprised to learn that this man who looked like a square, one who was a milquetoast and a candy-ass at that, had the FBI open a file on him. In fact, some of J. Edgar Hoover“s men at the Federal Bureau of Investigation were secretly reading Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat to find out if some of these books intended for kids might have any negative effects on the morale of soldiers, in case their fathers or older brothers had a peek at these stories as well, whether this constituted grounds for a charge of sedition. A memo, apparently from the office of J. Edgar Hoover himself, named Kurtzman, Gaines and artist Jack Davis as well as those two series. The file was closed in 1953. But still, there was something subversive going on when Kurtzman and company brought his scripts to life. The realism of these stories seemed to come rather from within than from what Kurtzman“s research had yielded him. These were not tales about heroism as it was commonly defined. These were tales in which the silence of the men who had lived through it all was all-encompassing. If for example, you looked at brawny Sergeant Purvis, the previously mentioned drill instructor, Stanley Kubrick“s movie “Full Metal Jacket”“ immediately came to mind. Though “Devils In Baggy Pants!”“ from Two-Fisted Tales No. 20 (1951) is not told from the point of view of another soldier who witnesses the abuse another private receives from his Gunnery Sergeant, but from the perspective of the sergeant himself, both start very similarly. Whereas in the Kubrick film, it is the sergeant who nicknames Private Leonard Lawrence “Gomer Pyle”“ (after the character from The Andy Griffith Show who was spun off onto his own show Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.) to indicate that he has the same situation on his hands like when the naïve, eccentric and slow TV character had joined up, he does so to denigrate and isolate Lawrence. However, TV“s Pyle“s character traits are coded as gay, and this was what the sergeant suggested about Lawrence towards his comrades. He was implying that here was a guy you could pick on, you should pick on, because he did not belong in the Marine Corps. In the story by Kurtzman and Wood, Sergeant Purvis gleefully tells readers that it was the outfit that had given a young recruit named Albert Smith his nickname “Duck-Butt”“ to reflect his cowardice. That Wood gives Smith an effete, feminine look with facial features that nigh make him appear as if he were a pretty girl, only adds to the subtext Kurtzman is going for. Since Albert looks soft, he must be a coward. And since he was a coward who looked like a girl this gave the sergeant the more reason to pick on him and to let the other men know that they had somebody among them who did not belong with the paratroopers. It is not surprising that themes like gender fluidity and the calling into question of gender identity were very much on the minds of not only these two creators but also those of many men during these times, and especially in male dominated environment such as the Army. And with masculinity under attack it seemed, this wouldn“t be the only tale among Wood“s EC work that tackled this subject. The movie and the comic play out very differently, though. Whereas in the Kubrick film, Private Leonard can“t take the constant harassment any longer and he first kills his drill instructor Sergeant Hartman and then himself, in the Kurtzman and Wood story, Albert“s infantry regiment is called up before anyone gets physically hurt, though not for Sergeant Purvis“ lack of trying. Once the men take heavy fire over France and are pin pointed at a strategically important bridge, their assignment turns into a suicide mission. Those who have survived the initial mauling by German machine guns, know they will have to blow up the bridge, lest the enemy is able to move their armored vehicles to the beach which is getting invaded by the allies at the same time. But by doing so, they have no way to withdraw. And after another attack, there is no one left but Purvis, Albert and one more man. It“s their lives against all those lives of their comrades on the beach. While the other guy sets the charges on the bridge and Albert keeps the German infantry at bay who is moving in on them, Purvis quickly makes a beeline across the bridge and to safety while it is Albert who valiantly holds the Germans back until the bridge is blown to pieces, at the cost of his own life. Purvis, who is telling this story to troops who have found him, is clearly shell-shocked, but it is also the moment of truth for him: “Pvt. Albert Smith was dead! ”˜Cowardly“ Duck-Butt Smith was dead. And where was the brave tough Sergeant Purvis when the fire-works broke out? There was though Sergeant Purvis! Cowering in a ditch! Left Duck-Butt to die at the gun, and ran to the rear to hide in a ditch! Big-mouthed Sergeant Purvis!”“ And whereas Albert Smith had been introduced with a soft look on his near innocent-looking, tender face, the story ended with a close-up shot of Sergeant Purvis“ haggard visage, a gaunt and emaciated grimace that betrayed that saving his own skin, had come for him with the price of a loss of his manhood. Not only had he run from enemy fire, but a young private who he had picked as a coward (and as a homosexual) had not. And still, there was nothing heroic about Albert“s sacrifice either. He was but one more dead soldier. But maybe he was the lucky one when compared to the main character from another Kurtzman and Wood story, one which introduced readers to a new expression.

painstakingly gather all the information he needed for a particular story, and then shape the narrative in a way that brought the essence to the forefront. Whereas Brando used raw, genuine and comparable experiences and emotions to build his characters from the insight out, like he was taught by his teacher Stella Adler, Harvey Kurtzman started with the external. He was a researcher. When Kurtzman crafted a story involving the Merchant Marine based on Wood“s suggestion, he did not press Wood for any specifics, instead he went ahead and wrote a story about an event Wood had heard a lot of stories about. This was not something Wally had lived through, and Kurtzman could have written about something that Wood did experience instead, but it never occurred to him. This was not the kind of realism Kurtzman was going for. These were no first-hand accounts or tale tales passed around by a group of veterans after many years had passed in an attempt to make sense of it all, to find meaning in the meaningless, in the random and the cruel. The early 50s were also a time when men who had been in combat situations, didn“t like to share their experiences with outsiders. This was also a time when a man could not admit to having been afraid. This was a time of a silent generation of men, some of which would find it hard to interact with their spouse or their kids. But when Wood, and also Kurtzman as an artist, put words into drawings that would go with the captions and the dialogue, something happened. If you were one of those who mistook Harvey Kurtzman for an insurance salesman, you were certainly surprised to learn that this man who looked like a square, one who was a milquetoast and a candy-ass at that, had the FBI open a file on him. In fact, some of J. Edgar Hoover“s men at the Federal Bureau of Investigation were secretly reading Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat to find out if some of these books intended for kids might have any negative effects on the morale of soldiers, in case their fathers or older brothers had a peek at these stories as well, whether this constituted grounds for a charge of sedition. A memo, apparently from the office of J. Edgar Hoover himself, named Kurtzman, Gaines and artist Jack Davis as well as those two series. The file was closed in 1953. But still, there was something subversive going on when Kurtzman and company brought his scripts to life. The realism of these stories seemed to come rather from within than from what Kurtzman“s research had yielded him. These were not tales about heroism as it was commonly defined. These were tales in which the silence of the men who had lived through it all was all-encompassing. If for example, you looked at brawny Sergeant Purvis, the previously mentioned drill instructor, Stanley Kubrick“s movie “Full Metal Jacket”“ immediately came to mind. Though “Devils In Baggy Pants!”“ from Two-Fisted Tales No. 20 (1951) is not told from the point of view of another soldier who witnesses the abuse another private receives from his Gunnery Sergeant, but from the perspective of the sergeant himself, both start very similarly. Whereas in the Kubrick film, it is the sergeant who nicknames Private Leonard Lawrence “Gomer Pyle”“ (after the character from The Andy Griffith Show who was spun off onto his own show Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.) to indicate that he has the same situation on his hands like when the naïve, eccentric and slow TV character had joined up, he does so to denigrate and isolate Lawrence. However, TV“s Pyle“s character traits are coded as gay, and this was what the sergeant suggested about Lawrence towards his comrades. He was implying that here was a guy you could pick on, you should pick on, because he did not belong in the Marine Corps. In the story by Kurtzman and Wood, Sergeant Purvis gleefully tells readers that it was the outfit that had given a young recruit named Albert Smith his nickname “Duck-Butt”“ to reflect his cowardice. That Wood gives Smith an effete, feminine look with facial features that nigh make him appear as if he were a pretty girl, only adds to the subtext Kurtzman is going for. Since Albert looks soft, he must be a coward. And since he was a coward who looked like a girl this gave the sergeant the more reason to pick on him and to let the other men know that they had somebody among them who did not belong with the paratroopers. It is not surprising that themes like gender fluidity and the calling into question of gender identity were very much on the minds of not only these two creators but also those of many men during these times, and especially in male dominated environment such as the Army. And with masculinity under attack it seemed, this wouldn“t be the only tale among Wood“s EC work that tackled this subject. The movie and the comic play out very differently, though. Whereas in the Kubrick film, Private Leonard can“t take the constant harassment any longer and he first kills his drill instructor Sergeant Hartman and then himself, in the Kurtzman and Wood story, Albert“s infantry regiment is called up before anyone gets physically hurt, though not for Sergeant Purvis“ lack of trying. Once the men take heavy fire over France and are pin pointed at a strategically important bridge, their assignment turns into a suicide mission. Those who have survived the initial mauling by German machine guns, know they will have to blow up the bridge, lest the enemy is able to move their armored vehicles to the beach which is getting invaded by the allies at the same time. But by doing so, they have no way to withdraw. And after another attack, there is no one left but Purvis, Albert and one more man. It“s their lives against all those lives of their comrades on the beach. While the other guy sets the charges on the bridge and Albert keeps the German infantry at bay who is moving in on them, Purvis quickly makes a beeline across the bridge and to safety while it is Albert who valiantly holds the Germans back until the bridge is blown to pieces, at the cost of his own life. Purvis, who is telling this story to troops who have found him, is clearly shell-shocked, but it is also the moment of truth for him: “Pvt. Albert Smith was dead! ”˜Cowardly“ Duck-Butt Smith was dead. And where was the brave tough Sergeant Purvis when the fire-works broke out? There was though Sergeant Purvis! Cowering in a ditch! Left Duck-Butt to die at the gun, and ran to the rear to hide in a ditch! Big-mouthed Sergeant Purvis!”“ And whereas Albert Smith had been introduced with a soft look on his near innocent-looking, tender face, the story ended with a close-up shot of Sergeant Purvis“ haggard visage, a gaunt and emaciated grimace that betrayed that saving his own skin, had come for him with the price of a loss of his manhood. Not only had he run from enemy fire, but a young private who he had picked as a coward (and as a homosexual) had not. And still, there was nothing heroic about Albert“s sacrifice either. He was but one more dead soldier. But maybe he was the lucky one when compared to the main character from another Kurtzman and Wood story, one which introduced readers to a new expression.

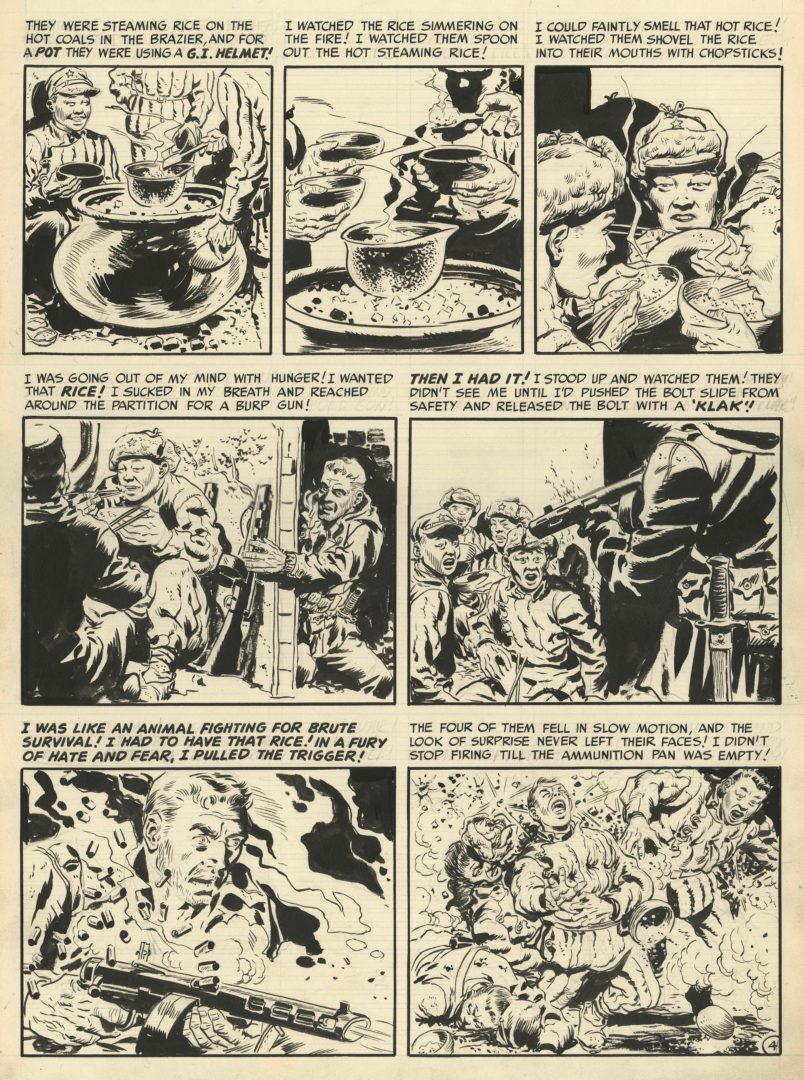

Though Kurtzman had never been abroad to fight in The Second World War, he instinctively understood the many horrors that came with war. Not only physical injuries, but also, and maybe especially, those inflicted on the minds of the men. What today is called PTSD for short or post-traumatic stress disorder, had many names during many wars. There was battle fatigue, then there was shell-shocked, and many more terms were used to describe the same phenomenon of men (and women) who seemed alright on the outside and who would act completely normal until they were brought back to an traumatic event by such a simple thing as some other guy using the horn of his car. Once the war in Korea had begun, which also involved American troops, the expression “to bug out”“ was quickly  popularized by these very soldiers. To bug out means to retreat hastily. It can also mean to flee as quickly as you can without any pre-existing plan. But Kurtzman not only brought this phrasal verb into the vernacular of kids who acted out war scenarios with their plastic rifles and a group of other children from the neighborhood, but he gave it an additional layer of meaning. In “Bug Out!!”“ from Two-Fisted Combat No. 24 (1951) Kurtzman and Wood tell the story of a soldier named Valentine who is on tour in Korea. While his patrol had been able to avoid small-arms fire during most of the day, when they get shelled with mortar fire, they have no choice but to leave their position, to bug out. Any territory they had gained during their campaign is lost as the troops are now on their long way back. Matters get worse since not only do they run out of food, but they get attacked during the night by enemy soldiers. This is when Valentine bugs out again. He runs as fast as he can without looking back. Still during the same night, he makes it to an abandoned village where he falls asleep among the few heavily shelled walls that offer shelter to him. At daylight, when he comes to, he finds that he is no longer alone. On the other side of the wall he observers some Korean soldiers who have settled down for breakfast. The four men are at ease and they stand around a warming fire with their guns leaned against the wall. From the other side, Valentine can almost touch the sub-machine guns which look a lot like the tommy gun Wood would hold in the picture from 1980. But Valentine“s mind is not on the guns which are so close. His needs are much more basic than to now reach for an instrument that brings death. It is the rice the men steam that has his attention. Valentine is intent on surviving, and to obtain sustenance takes precedence over everything else. It is the sight of the rice and his hunger that motivates him into taking the lives of the four combatants first by reaching for one of the machine guns and then by unloading on them until the last bullet: “I was like an animal fighting for brute survival! I had to have that rice! In a fury of hate and fear, I pulled the trigger!”“ While he feeds, like “a hungry, wild-eyed dog”“, even scooping up food from the dirty ground, he is almost too late in realizing that there are bomber planes in the air above him, American planes. Two planes drop their bombs on the destroyed village, which is redundant, while here was one of their heroic comrades who further regressed into the state of a primitive animal: “I hugged the ground! I pressed against the ground! I tried to claw into the ground! An animal! A miserable wretched animal trying to crawl down into the ground!”“ Valentine“s eyes are bugged out with fear while he wonders: “What happened to me? What happened to all my fine civilized instincts?”“ It is with this panel that the story cuts to a hospital. It is a year later, and Valentine is in a wheelchair while a young nurse talks to him as she moves his chair closer to one of the windows assuming that this must be something he will enjoy. When another nurse joins her, the women discuss his case with Valentine closer to the window. As the first nurse explains: “Not a scratch on him! Yet he hasn“t said a word since he was found! Just stares out of the window!”“ It is not like the blonde soldier is unable to hear the conversation, but he chooses not to interact. It is the other nurse who judges him based on his appearance: “He looks like such a sensitive, gentle boy!”“ But Valentine has found out what he is: “I“m a killer! I“m an animal”¦ running through the dark with my tail between my legs! Growling around and killing for food! Hiding in the cracks between rocks!”“ That was what he was doing now. With this story, Kurtzman and Wood showed readers that “bug out”“ could also mean that you might “bug out”“ from life itself, that you became a shut-in, and stopped interacting with other human beings whenever the pain and the shame became too heavy. It was what war yielded you. Wood“s men looked like what heroes are supposed to look like, but there was nothing heroic in sacrifice. If you read Kurtzman“s words about Wood“s work ethics and about his “sacrifice”“ in the context in which he said and meant them, an image emerges that is devoid of any machismo and male bravado: “Wally devoted himself so intensely to his work that he burned himself out. He overworked his body”¦ he had that quality of frustration and tension”¦ I think it ate away his insides and the work really used him up.”“

popularized by these very soldiers. To bug out means to retreat hastily. It can also mean to flee as quickly as you can without any pre-existing plan. But Kurtzman not only brought this phrasal verb into the vernacular of kids who acted out war scenarios with their plastic rifles and a group of other children from the neighborhood, but he gave it an additional layer of meaning. In “Bug Out!!”“ from Two-Fisted Combat No. 24 (1951) Kurtzman and Wood tell the story of a soldier named Valentine who is on tour in Korea. While his patrol had been able to avoid small-arms fire during most of the day, when they get shelled with mortar fire, they have no choice but to leave their position, to bug out. Any territory they had gained during their campaign is lost as the troops are now on their long way back. Matters get worse since not only do they run out of food, but they get attacked during the night by enemy soldiers. This is when Valentine bugs out again. He runs as fast as he can without looking back. Still during the same night, he makes it to an abandoned village where he falls asleep among the few heavily shelled walls that offer shelter to him. At daylight, when he comes to, he finds that he is no longer alone. On the other side of the wall he observers some Korean soldiers who have settled down for breakfast. The four men are at ease and they stand around a warming fire with their guns leaned against the wall. From the other side, Valentine can almost touch the sub-machine guns which look a lot like the tommy gun Wood would hold in the picture from 1980. But Valentine“s mind is not on the guns which are so close. His needs are much more basic than to now reach for an instrument that brings death. It is the rice the men steam that has his attention. Valentine is intent on surviving, and to obtain sustenance takes precedence over everything else. It is the sight of the rice and his hunger that motivates him into taking the lives of the four combatants first by reaching for one of the machine guns and then by unloading on them until the last bullet: “I was like an animal fighting for brute survival! I had to have that rice! In a fury of hate and fear, I pulled the trigger!”“ While he feeds, like “a hungry, wild-eyed dog”“, even scooping up food from the dirty ground, he is almost too late in realizing that there are bomber planes in the air above him, American planes. Two planes drop their bombs on the destroyed village, which is redundant, while here was one of their heroic comrades who further regressed into the state of a primitive animal: “I hugged the ground! I pressed against the ground! I tried to claw into the ground! An animal! A miserable wretched animal trying to crawl down into the ground!”“ Valentine“s eyes are bugged out with fear while he wonders: “What happened to me? What happened to all my fine civilized instincts?”“ It is with this panel that the story cuts to a hospital. It is a year later, and Valentine is in a wheelchair while a young nurse talks to him as she moves his chair closer to one of the windows assuming that this must be something he will enjoy. When another nurse joins her, the women discuss his case with Valentine closer to the window. As the first nurse explains: “Not a scratch on him! Yet he hasn“t said a word since he was found! Just stares out of the window!”“ It is not like the blonde soldier is unable to hear the conversation, but he chooses not to interact. It is the other nurse who judges him based on his appearance: “He looks like such a sensitive, gentle boy!”“ But Valentine has found out what he is: “I“m a killer! I“m an animal”¦ running through the dark with my tail between my legs! Growling around and killing for food! Hiding in the cracks between rocks!”“ That was what he was doing now. With this story, Kurtzman and Wood showed readers that “bug out”“ could also mean that you might “bug out”“ from life itself, that you became a shut-in, and stopped interacting with other human beings whenever the pain and the shame became too heavy. It was what war yielded you. Wood“s men looked like what heroes are supposed to look like, but there was nothing heroic in sacrifice. If you read Kurtzman“s words about Wood“s work ethics and about his “sacrifice”“ in the context in which he said and meant them, an image emerges that is devoid of any machismo and male bravado: “Wally devoted himself so intensely to his work that he burned himself out. He overworked his body”¦ he had that quality of frustration and tension”¦ I think it ate away his insides and the work really used him up.”“