“WHATEVER WALKED THERE, WALKED ALONE” THE CHILDREN OF THE NIGHT, PART 3

There is something deeply subversive that goes hand in hand with picking up, picking out and actually reading comic books, especially comic books. Any type of literature is made up of ideas, stemming from either vast imagination or an author’s interpretation of the state of the world. Once written down with the intention of not only preserving these observations as a record of private recollections, but to allow others access to them, to disseminate them in a targeted manner or indiscriminately, this is when any construct of words strung together in sentences becomes the most dangerous thing in the world. There is a reason why in medieval times the ability to write and read was exclusive to members of the ruling class, the aristocracy and the clergy. To express ideas, to make them knowable to others becomes much more powerful a tool once it arrives in the hands of the unwashed masses. Sure, legends and lore always had a way of finding the ears of many excitable listeners, and there were the breathless campfire tales, narrated against the backdrop of crackling dry wood, buzzing sparks and whirring firebugs. These were the stories of great hunts and glorious battles, reports about men that had espoused a life of service, of bravery and chivalry, men whose biographies were to serve as role models for the common folk. The tales also spoke about the pitfalls, the dangers that lay ahead. Never trust a shifty-looking foreigner, or a woman whose beauty was liable to offend the gods, or God. Still, these oral narratives tried to make sense of it all. As such, these were plenty. The  monarchs were noble and just, benevolent dictators who always knew what was best, at least according to these oft-told stories. Knowledge however, it became the greatest threat. Once an ever-increasing number of people was able to read, to write and to express their thoughts in a medium that not only retained them but allowed for mass-reproduction, any empire might topple overnight. Naturally, the ruling class could not let this stand unchallenged. Writing which was viewed as ‘fiction”, and thus presented an alternative to the way the world was, in that its authors envisioned what a better world might look like and how it could be brought about, and worse still, made almost palpable by the vivid descriptions supplied, it needed to be squashed in its infancy. What better means for the ruling class than to have its appointed, tolerated and mightily self-satisfied intelligentsia discredit such works as fanciful reveries without any claim on actuality or any right to the readers’ time. Should any such venom of savage criticism from those masterminds and connoisseurs of fine literature not suffice, how quite easily were the masses enticed to attack what they were told was bad not simply to their well-being on the material world yet once they shuffled off this mortal coil, to their eternal soul. Thus, no sooner had the writing of manuscripts become a thing, there were those waiting in the wings to set fire to the very pages that held these dangerous words. Strangely but perhaps not surprisingly at all, those perpetrating the deed will always view themselves as the heroes like chivalrous knights from lore and legend. It’s often the young, those who have yet to understand that in the middle ground that lies between black and white there’s ample estate for the grays to exist, the young who cling tightly to the most orthodox set of beliefs as if the very same constitutes a life boat while they’re lost at sea, who will get radicalized the quickest. Whereas today, young intellectuals view it as their holy mission to rob works of fiction of their sense of adventure, their ability to frighten readers with uncomfortable words, to stir the readers’ imagination, and if these a truly powerful works of art, the ability to challenge core values and popular beliefs as they hint at something deeper, something hidden, only a few generations prior, their peers seized 25,000 books from the library of their university. Those students who burned books that promoted what they believed were dangerous thoughts on politics, sociology, art and sexual orientation, they believed themselves the good guys as well. As they sought to replace the works of art they wanted to see expunged not only from the collective memory but from existence, with works that were vapid, shallow, sanitized, safe and most importantly, reflected the unchallenged thoughts which reverberated from the walls of their private echo chambers to provide great comfort, there was nobody holding a gun to their heads. In fact, the true horror story of what occurred on May 10, 1933 in a public place, namely in the square right in front of the Berlin Opera, is that the members of the student union, these young men clad in smart suits with ties, and the young women with their neat blouses and pencil skirts, were as far removed from any basement dwelling thug in a brown shirt you can imagine. This act of targeted destruction of the works of writers whose ideas they deemed offensive, to see the shelves at the library of their university stocked with all types of books as long as they were inoffensive, it was not censorship ordered by their government. These students were not mandated to act, nor were they forced. While the concept of ‘Gleichschaltung” has merit in every totalitarian system, the consolidation of institutional power, the consolidation of speech and of thought which doesn’t allow for any divergent ideas, not even in the deepest and furthest recesses of one’s mind, with everything else replaced with the credo that says that you must choose, you are either for us or you will be against us, it doesn’t apply in this case. Surely, much solace can be gleaned from a revised history in which only a handful of villains are responsible and everyone else was merely a misinformed dupe, a follower at best, not an instigator, but historical facts care little for what you want them to say nor do they care for your feelings. Whereas today people will tell you that physically threatening a political opponent is alright, that punching a man in the face is justified, that destroying his livelihood and that of his family is a legitimate means if your goals are noble, and since you are they good guys, the students who burned the books of many writers such as H.G. Wells, Thomas Mann and Stefan Zweig, they would have told you just the same. How wildly shocking then, that nobody outside the rhetoric these German students had adopted as their own, who learned of their deed was to commend them. Quite the contrary as writers from across the globe loudly condemned these self-appointed and self-satisfied arbiters of taste and the right kind of morals. Maybe Helen Keller, a writer who was very much not in the Nazi ideal since she was deaf-blind and had to work for everything she’d achieved with nobody handing her a participation trophy for just showing up, she said it best when she wrote: ‘You may burn my books and the books of the best minds of Europe, but the ideas those books contain have passed through millions of channels and will go on.” But if you were a young student in Berlin in 1933, you cared little for Keller or her words, however there needed to be an end to those ideas which you hated that still reached millions. So, why stop with just burning books? If this didn’t silence the voices you didn’t want to hear, you didn’t want others to hear, you knew that you had to go to the source. In a perfect world there’s no room for deviants, there’s no place for misfits.

monarchs were noble and just, benevolent dictators who always knew what was best, at least according to these oft-told stories. Knowledge however, it became the greatest threat. Once an ever-increasing number of people was able to read, to write and to express their thoughts in a medium that not only retained them but allowed for mass-reproduction, any empire might topple overnight. Naturally, the ruling class could not let this stand unchallenged. Writing which was viewed as ‘fiction”, and thus presented an alternative to the way the world was, in that its authors envisioned what a better world might look like and how it could be brought about, and worse still, made almost palpable by the vivid descriptions supplied, it needed to be squashed in its infancy. What better means for the ruling class than to have its appointed, tolerated and mightily self-satisfied intelligentsia discredit such works as fanciful reveries without any claim on actuality or any right to the readers’ time. Should any such venom of savage criticism from those masterminds and connoisseurs of fine literature not suffice, how quite easily were the masses enticed to attack what they were told was bad not simply to their well-being on the material world yet once they shuffled off this mortal coil, to their eternal soul. Thus, no sooner had the writing of manuscripts become a thing, there were those waiting in the wings to set fire to the very pages that held these dangerous words. Strangely but perhaps not surprisingly at all, those perpetrating the deed will always view themselves as the heroes like chivalrous knights from lore and legend. It’s often the young, those who have yet to understand that in the middle ground that lies between black and white there’s ample estate for the grays to exist, the young who cling tightly to the most orthodox set of beliefs as if the very same constitutes a life boat while they’re lost at sea, who will get radicalized the quickest. Whereas today, young intellectuals view it as their holy mission to rob works of fiction of their sense of adventure, their ability to frighten readers with uncomfortable words, to stir the readers’ imagination, and if these a truly powerful works of art, the ability to challenge core values and popular beliefs as they hint at something deeper, something hidden, only a few generations prior, their peers seized 25,000 books from the library of their university. Those students who burned books that promoted what they believed were dangerous thoughts on politics, sociology, art and sexual orientation, they believed themselves the good guys as well. As they sought to replace the works of art they wanted to see expunged not only from the collective memory but from existence, with works that were vapid, shallow, sanitized, safe and most importantly, reflected the unchallenged thoughts which reverberated from the walls of their private echo chambers to provide great comfort, there was nobody holding a gun to their heads. In fact, the true horror story of what occurred on May 10, 1933 in a public place, namely in the square right in front of the Berlin Opera, is that the members of the student union, these young men clad in smart suits with ties, and the young women with their neat blouses and pencil skirts, were as far removed from any basement dwelling thug in a brown shirt you can imagine. This act of targeted destruction of the works of writers whose ideas they deemed offensive, to see the shelves at the library of their university stocked with all types of books as long as they were inoffensive, it was not censorship ordered by their government. These students were not mandated to act, nor were they forced. While the concept of ‘Gleichschaltung” has merit in every totalitarian system, the consolidation of institutional power, the consolidation of speech and of thought which doesn’t allow for any divergent ideas, not even in the deepest and furthest recesses of one’s mind, with everything else replaced with the credo that says that you must choose, you are either for us or you will be against us, it doesn’t apply in this case. Surely, much solace can be gleaned from a revised history in which only a handful of villains are responsible and everyone else was merely a misinformed dupe, a follower at best, not an instigator, but historical facts care little for what you want them to say nor do they care for your feelings. Whereas today people will tell you that physically threatening a political opponent is alright, that punching a man in the face is justified, that destroying his livelihood and that of his family is a legitimate means if your goals are noble, and since you are they good guys, the students who burned the books of many writers such as H.G. Wells, Thomas Mann and Stefan Zweig, they would have told you just the same. How wildly shocking then, that nobody outside the rhetoric these German students had adopted as their own, who learned of their deed was to commend them. Quite the contrary as writers from across the globe loudly condemned these self-appointed and self-satisfied arbiters of taste and the right kind of morals. Maybe Helen Keller, a writer who was very much not in the Nazi ideal since she was deaf-blind and had to work for everything she’d achieved with nobody handing her a participation trophy for just showing up, she said it best when she wrote: ‘You may burn my books and the books of the best minds of Europe, but the ideas those books contain have passed through millions of channels and will go on.” But if you were a young student in Berlin in 1933, you cared little for Keller or her words, however there needed to be an end to those ideas which you hated that still reached millions. So, why stop with just burning books? If this didn’t silence the voices you didn’t want to hear, you didn’t want others to hear, you knew that you had to go to the source. In a perfect world there’s no room for deviants, there’s no place for misfits.

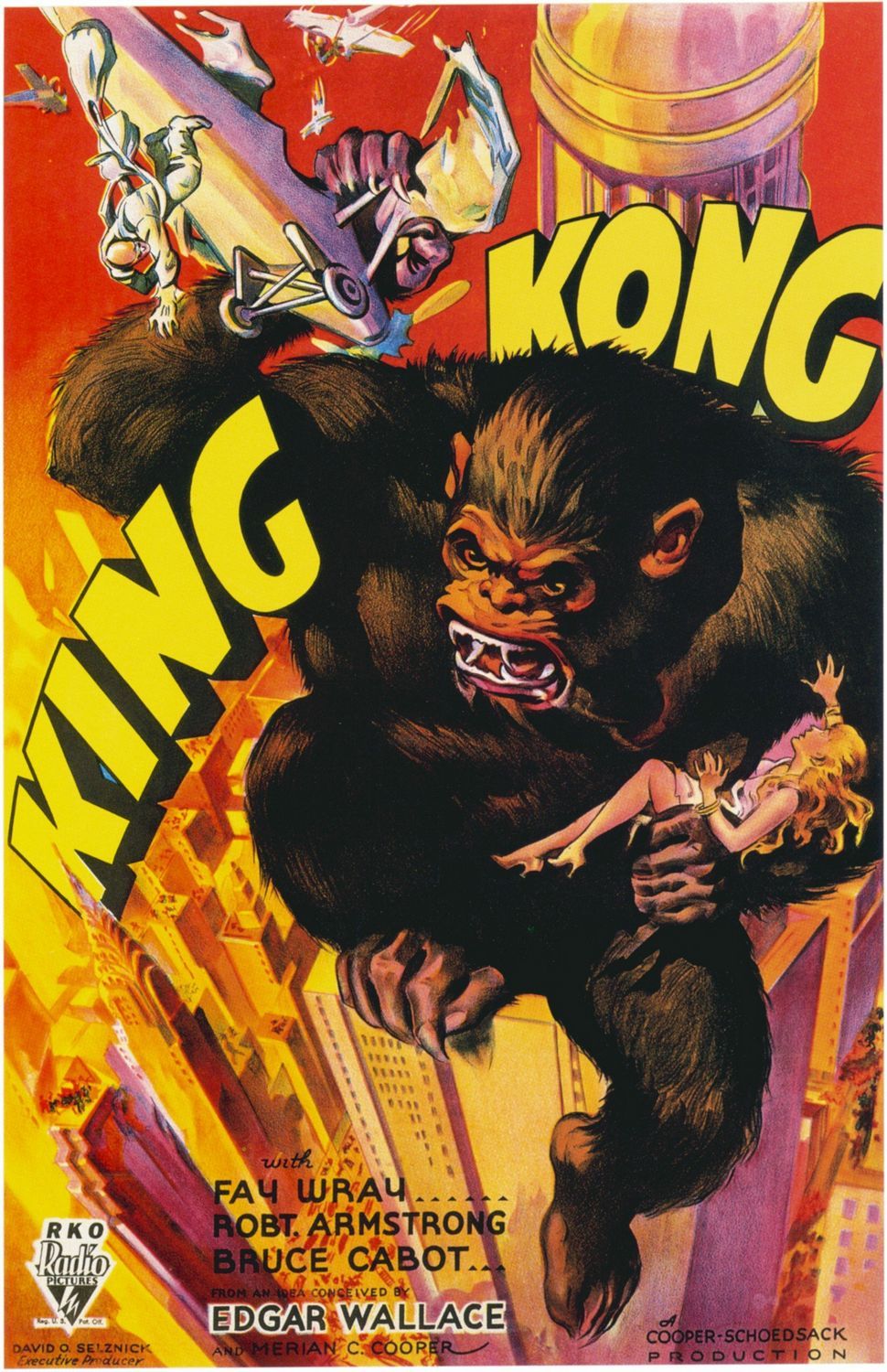

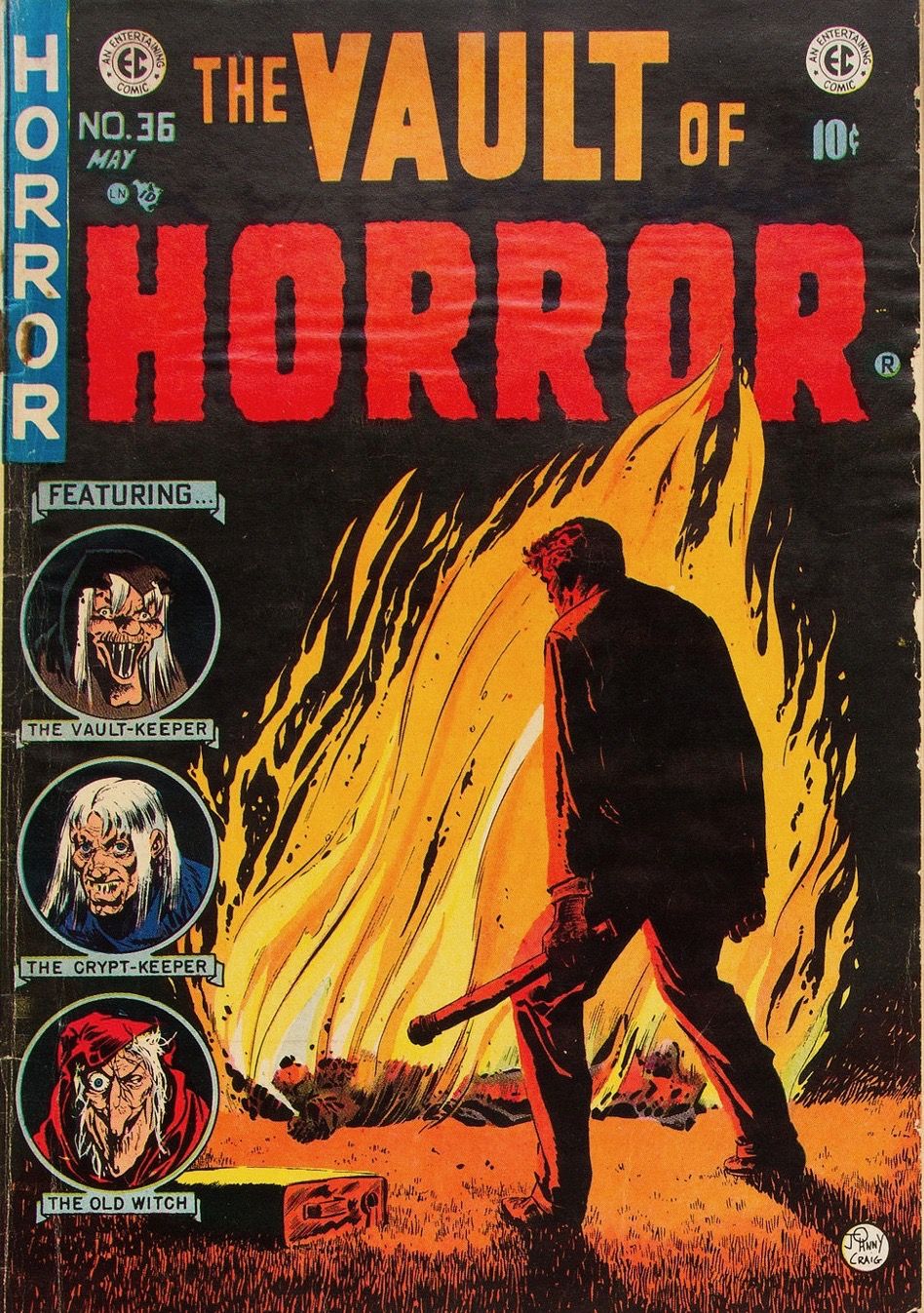

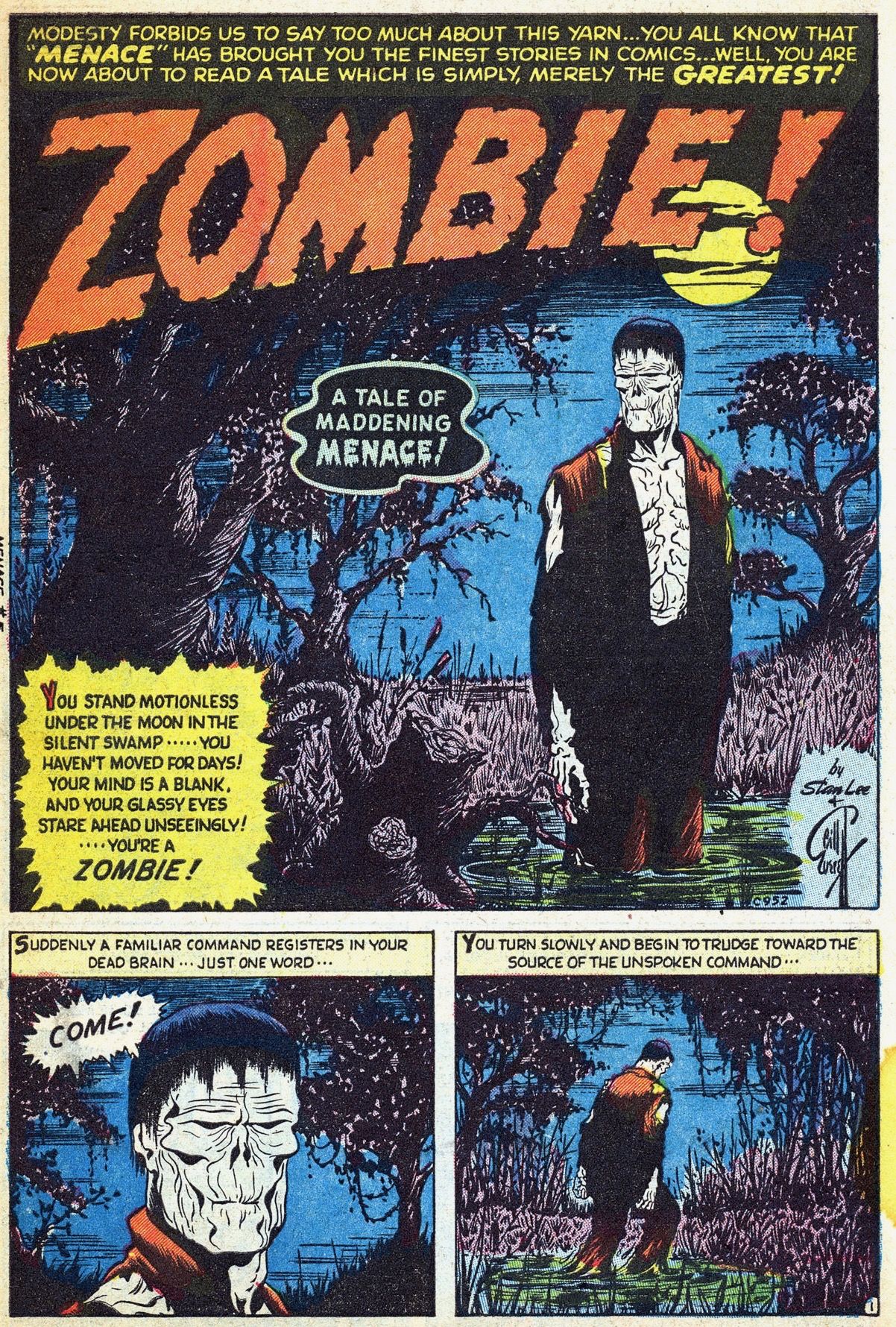

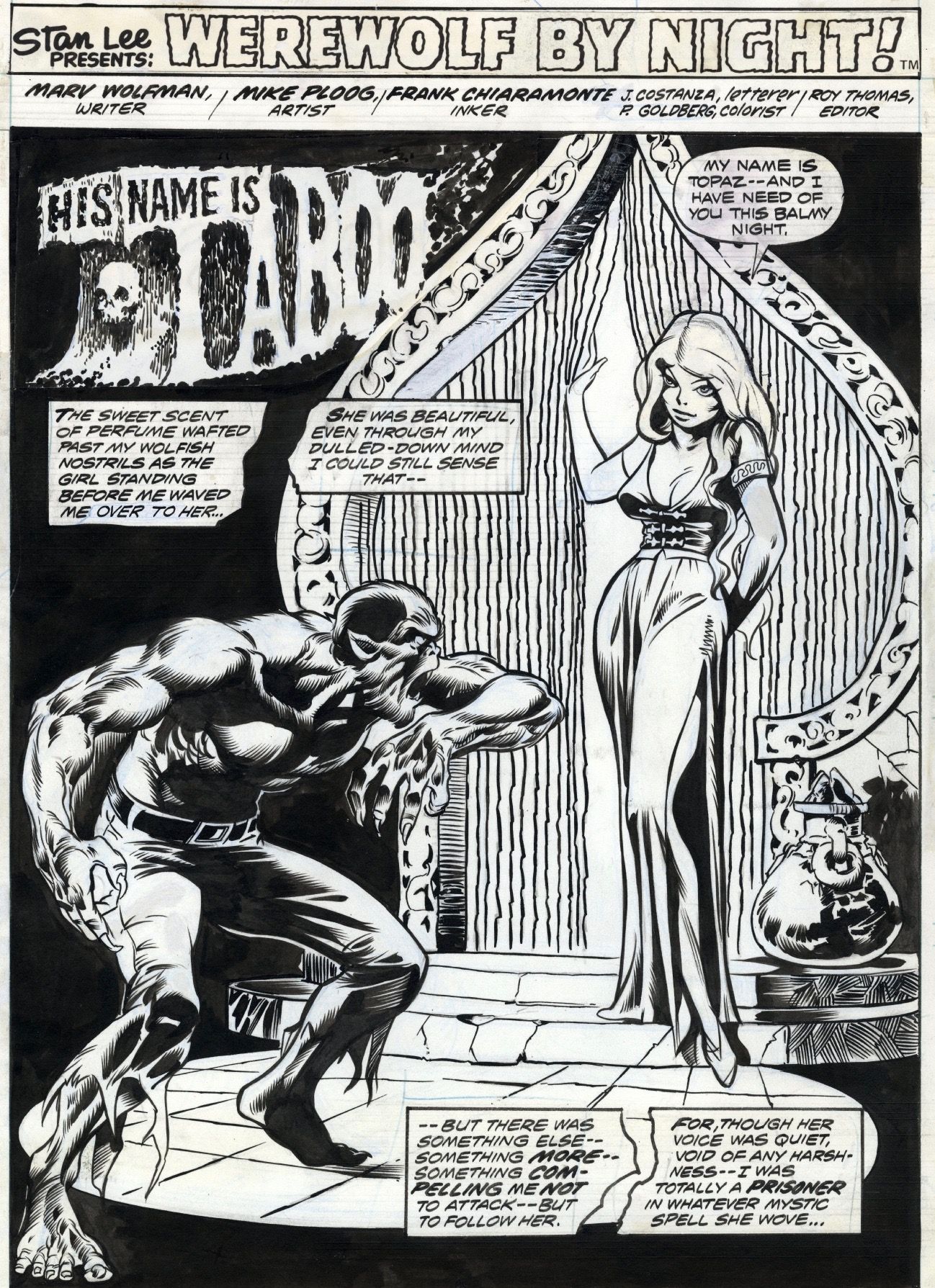

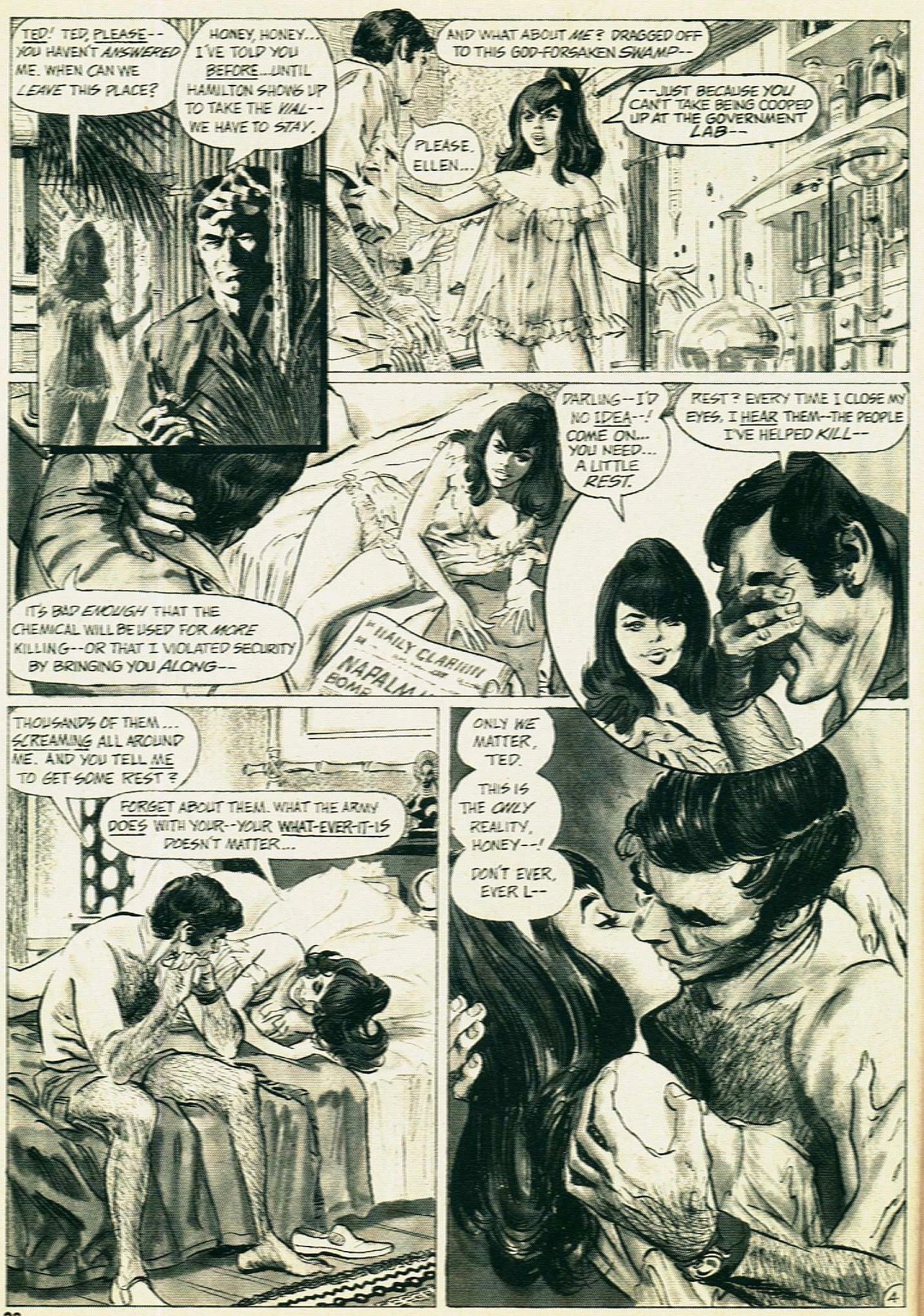

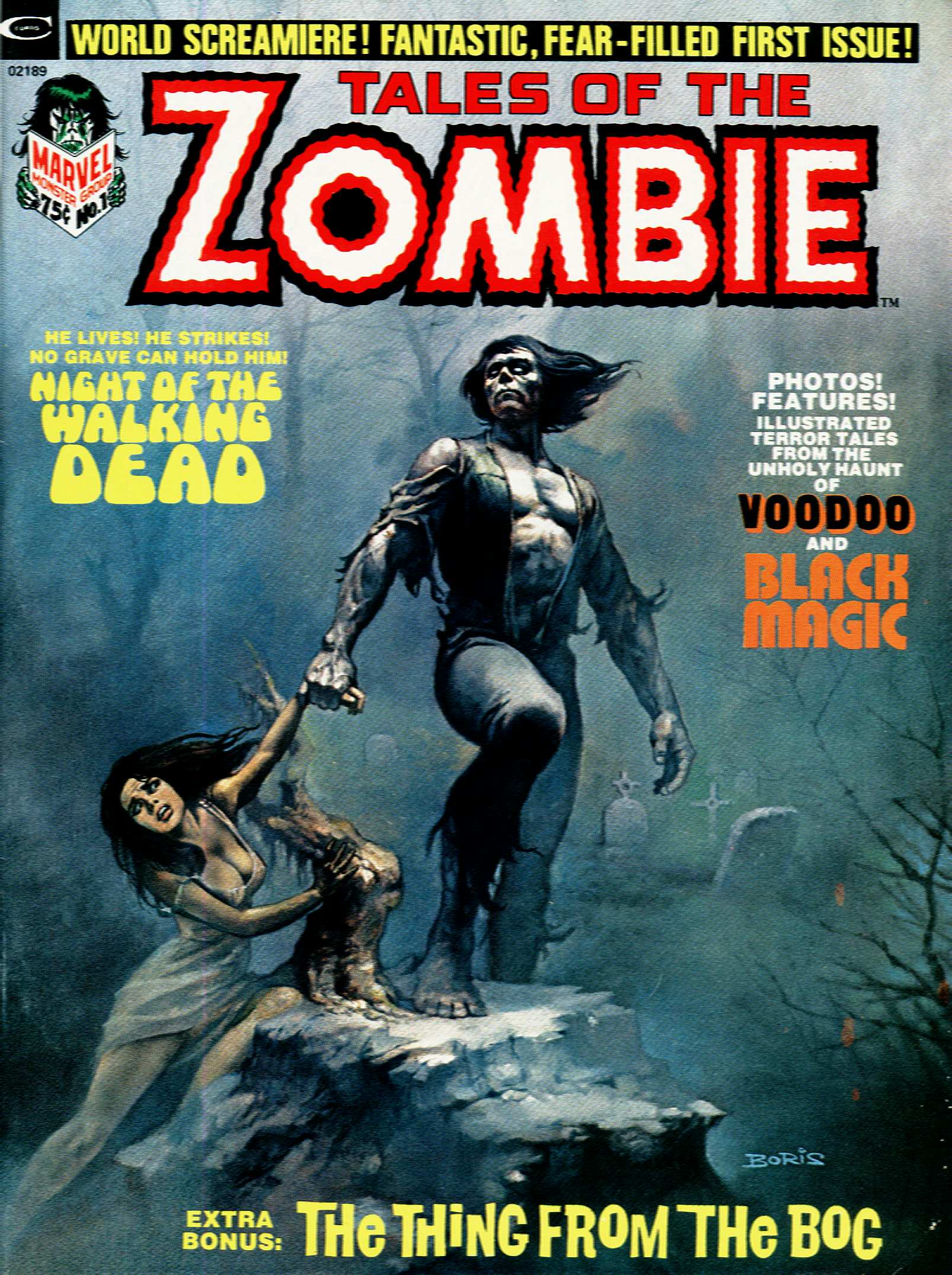

If you were a child in the late 1940s, the idea that they burned the outsiders, the misfits of society, was very familiar to you, especially if you liked the monsters. And why wouldn’t you when you are a child. When you watch ‘King Kong” (1933) at an early age, there’s something about this giant ape that is much less frightening but so much more endearing. Here is this clumsy beast that shows little regard for these tiny savages that worship him out of fear and who offer him their daughters in an act of appeasement. The monster remains unimpressed, but once he lays eyes on the blonde woman who has arrived on his hidden island, Kong goes weak in the knees and acts all awkward not unlike any schoolboy would once he spots the girl, he has a crush on. The giant ape is not so different from us. He’s looking for acceptance and love. He’s an outsider in his own home, the native fear him, they don’t love him. You also pity Kong when he falls to his death from the Empire State Building as he’s wounded by rifle fire from bi-planes, signifiers of man’s mastery of nature. It is only once a boy hits puberty that he’ll notice how see-through and flimsy Fay Wray’s gowns truly are, or if you are girl, you can’t help but notice the muscles the film’s leading man Bruce Cabot knows how to show off. With every subsequent release of the film in theatres or across television screens, the horror aspects presented are pushed further into the background due to the changing times (with some of the more terrifying scenes of the movie edited from the picture as demanded by Hay’s Code and later for television broadcast). What viewers of ‘King Kong” are left with is a tale of the beauty and the beast, a fairy tale which is especially appealing to children. Yet this is also the film that teaches you about censorship. Not censorship done by a government for political reasons, but for monetary gain, and born from the unholy  middle ground between good intentions and the lust for the power to tell others how to live their lives, which isn’t without its own irony since the things that will very often get censored have to do with lust. Religious groups in certain domestic markets couldn’t allow Ms. Wray’s wardrobe to be that transparent, thus, not to risk a costly boycott, the movie’s studio RKO agreed to cut certain scenes in these markets. Why alienate your moviegoing audience, men and women who could be so easily influenced by a handful of self-appointed zealots with their holier than though virtue signaling attitude of moralistic righteousness? Have them buy a movie ticket instead. But this wasn’t all. If a boy watching the film was attracted to how Bruce Cabot’s shredded abs moved under his t-shirt instead of being fascinated by the outlines of Fay Wray’s erect nipples, he knew this was bad. Likewise, if you were a girl and you did enjoy what you saw of the blonde lead actress a bit too much or too much in a way that you instinctively knew was deemed normal. Surely, a girl was allowed to notice how pretty another girl was, but anything beyond that were dangerous thoughts. And in the late 1940s, children knew about those dangerous thoughts. If regular books might already contain wrong thinking, what about the comic books? They came with pictures, often very lurid, sexualized images. You needn’t be able to read properly to get what was going on. Comics combined the lore and legends of heroes as told at a crackling bonfire with the images that indigenous people drew with paint fashioned from clay on the walls of their caves, or earlier, highly civilized nations used to describe the exploits of their noble supergods. Comic books did this as well, and you got these images and words without having to visit a cave, a pyramid, a temple or a church. For just ten cents paid to a vendor at a newsstand you could take these adventures home. That was as long as comic books were useful to the U.S. government as a tool for propaganda in the war effort. Once they lost this powerful protector in Uncle Sam, as kids began to lose interest in the superhero but not in the comics themselves just yet, these cheap pamphlets in what was still a very young industry that was too wide-eyed and bushy-tailed to realize the dangers that lay ahead, they became prey for the very same men and women who’d come for the motion pictures and the pulp magazines. As kids left the superheroes behind and turned their attention to the crime comics and the romance books, soon so-called culture critics and child psychologists began to circulate articles that tied isolated cases of perceived deviant behavior in young children and adolescents to one source exclusively. The four-colored manifestos with their unbridled depiction of heinous violence and wanton sexuality were to blame. Not that there weren’t any dissenting voices. Professionals from wide-ranging fields of expertise, such as psychiatrists and employees in the prison and corrections system, were ready to offer their two cents, with their testimony on the matter quickly reprinted in easily digestible quotes in the editorial pages of the very same comic books that found themselves under attack. At Timely, one of the smaller comic book publishers, the newly appointed ‘Managing Editor, Director of Art”, launched a series of op-ed pieces at the same time he rebranded their offerings as ‘Marvel Magazines”. His name was Stan Lee. In his articles, Lee acknowledged that there were some rotten apples, but he trusted that their readers could tell the good ones from the bad ones, and quite naturally, if you picked up a Marvel book this inoculated you from any criticism. In fact, the idea that comic books were an unhealthy hobby, wasn’t even a new one when men like Dr. Fredric Wertham latched onto the idea that criticizing comics would garner much publicity. The thought had percolated into the mind of the American public as soon as first the superheroes had put on colorful costumes, and especially once such he-men were joined by their very own underage sidekicks and superheroines who dressed like no decent young woman was to show herself in public. Publishers were wise to empanel advisory boards made up of leading educators to ensure parents that their titles were vetted by these renowned childcare specialists. What had saved the heroes and comic books back then, was their value for the propaganda machine of the military, one more example of the Military-Industrial Complex in action. However, once the decade drew to a close, and with the war in the rear-view mirror and the government interested in establishing a middle class that lived comfortably secluded (and intellectually isolated) in the new suburbia, PTA representatives, college deans hungry for their moment in the spotlight and preachers from various congregations, now armed with their own expert witnesses renewed their attacks on the comic books. Dr. Fredric Wertham, actually a very progressive thinker, who had long since been looking for a subject for a series of articles, not those shunted away in some of the medical journals that were only glanced at by his peers if at all, but with some powerful hook that worked like a Molotov cocktail, couldn’t have published his article ‘The Comics, Very Funny” at a more opportune moment in time. Ostensibly a rather loosely written but very gut-wrenching sampling of some accounts of child-on-child violence (including a shocking example of sexual violence perpetrated by young children), he claimed came from his private practice as a child psychologist working on authentic police cases, a claim that sounded suspiciously like the made-up ones used in the crime comic books, his cases did reveal a common thread. His patients were avid readers of comic books. ‘The Comics, Very Funny” appeared on May 29, 1948 in the Saturday Review of Literature. Hardly anybody noticed. Had he lived today, his observations (which these were since the good doctor offered no actual facts, neither about the cases he ever so briefly presented nor for what his conclusions were based on), would have found their way to various social networks, only to be hotly debated among many posters with an opinion to share and no time to do any actual research. But as luck would have it for Wertham, back then there was the next best thing. Reader’s Digest was the publication you wanted to subscribe to if you lived in any of those new dream model homes in the suburbs if you felt you needed some cursory familiarity with current cultural and slightly political topics for the next cocktail party you attended. Rather than requiring you to read articles from newspapers, journals and magazines, honestly who had the time, Reader’s Digest offered you a sampler of carefully curated publications in condensed form. In August 1948, an abbreviated version of his opinion piece made it into the magazine which then was disseminated to several million households. One speech by Hitler’s Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels (who held a doctor of philology degree), actually delivered some months prior to the events on May 10, 1933, was enough to whip the student body of Berlin University into a frenzy. With the war going on, comic books were protected. For one, since they served a purpose, but also because they were popular. But as Stan Lee could have told you, once 1947 turned into 1948, and with his new job title only a few months old, this was no longer the case. Children were buying crime comics in droves and then there were the new romance comics (invented by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby), but the number of new readers was fairly small compared to the readers that were getting out of comic books. Reading comics was no longer the hip thing to do, too closely were they tied to the days of the depression and the war. If you read Superman stories in Action Comics as a child, now as a student in middle school or as a freshman in high school, you felt embarrassed whenever people mentioned them, or worse, when folks recalled having seen you reading such trash. You were almost an adult. Comics, they were for kids.

middle ground between good intentions and the lust for the power to tell others how to live their lives, which isn’t without its own irony since the things that will very often get censored have to do with lust. Religious groups in certain domestic markets couldn’t allow Ms. Wray’s wardrobe to be that transparent, thus, not to risk a costly boycott, the movie’s studio RKO agreed to cut certain scenes in these markets. Why alienate your moviegoing audience, men and women who could be so easily influenced by a handful of self-appointed zealots with their holier than though virtue signaling attitude of moralistic righteousness? Have them buy a movie ticket instead. But this wasn’t all. If a boy watching the film was attracted to how Bruce Cabot’s shredded abs moved under his t-shirt instead of being fascinated by the outlines of Fay Wray’s erect nipples, he knew this was bad. Likewise, if you were a girl and you did enjoy what you saw of the blonde lead actress a bit too much or too much in a way that you instinctively knew was deemed normal. Surely, a girl was allowed to notice how pretty another girl was, but anything beyond that were dangerous thoughts. And in the late 1940s, children knew about those dangerous thoughts. If regular books might already contain wrong thinking, what about the comic books? They came with pictures, often very lurid, sexualized images. You needn’t be able to read properly to get what was going on. Comics combined the lore and legends of heroes as told at a crackling bonfire with the images that indigenous people drew with paint fashioned from clay on the walls of their caves, or earlier, highly civilized nations used to describe the exploits of their noble supergods. Comic books did this as well, and you got these images and words without having to visit a cave, a pyramid, a temple or a church. For just ten cents paid to a vendor at a newsstand you could take these adventures home. That was as long as comic books were useful to the U.S. government as a tool for propaganda in the war effort. Once they lost this powerful protector in Uncle Sam, as kids began to lose interest in the superhero but not in the comics themselves just yet, these cheap pamphlets in what was still a very young industry that was too wide-eyed and bushy-tailed to realize the dangers that lay ahead, they became prey for the very same men and women who’d come for the motion pictures and the pulp magazines. As kids left the superheroes behind and turned their attention to the crime comics and the romance books, soon so-called culture critics and child psychologists began to circulate articles that tied isolated cases of perceived deviant behavior in young children and adolescents to one source exclusively. The four-colored manifestos with their unbridled depiction of heinous violence and wanton sexuality were to blame. Not that there weren’t any dissenting voices. Professionals from wide-ranging fields of expertise, such as psychiatrists and employees in the prison and corrections system, were ready to offer their two cents, with their testimony on the matter quickly reprinted in easily digestible quotes in the editorial pages of the very same comic books that found themselves under attack. At Timely, one of the smaller comic book publishers, the newly appointed ‘Managing Editor, Director of Art”, launched a series of op-ed pieces at the same time he rebranded their offerings as ‘Marvel Magazines”. His name was Stan Lee. In his articles, Lee acknowledged that there were some rotten apples, but he trusted that their readers could tell the good ones from the bad ones, and quite naturally, if you picked up a Marvel book this inoculated you from any criticism. In fact, the idea that comic books were an unhealthy hobby, wasn’t even a new one when men like Dr. Fredric Wertham latched onto the idea that criticizing comics would garner much publicity. The thought had percolated into the mind of the American public as soon as first the superheroes had put on colorful costumes, and especially once such he-men were joined by their very own underage sidekicks and superheroines who dressed like no decent young woman was to show herself in public. Publishers were wise to empanel advisory boards made up of leading educators to ensure parents that their titles were vetted by these renowned childcare specialists. What had saved the heroes and comic books back then, was their value for the propaganda machine of the military, one more example of the Military-Industrial Complex in action. However, once the decade drew to a close, and with the war in the rear-view mirror and the government interested in establishing a middle class that lived comfortably secluded (and intellectually isolated) in the new suburbia, PTA representatives, college deans hungry for their moment in the spotlight and preachers from various congregations, now armed with their own expert witnesses renewed their attacks on the comic books. Dr. Fredric Wertham, actually a very progressive thinker, who had long since been looking for a subject for a series of articles, not those shunted away in some of the medical journals that were only glanced at by his peers if at all, but with some powerful hook that worked like a Molotov cocktail, couldn’t have published his article ‘The Comics, Very Funny” at a more opportune moment in time. Ostensibly a rather loosely written but very gut-wrenching sampling of some accounts of child-on-child violence (including a shocking example of sexual violence perpetrated by young children), he claimed came from his private practice as a child psychologist working on authentic police cases, a claim that sounded suspiciously like the made-up ones used in the crime comic books, his cases did reveal a common thread. His patients were avid readers of comic books. ‘The Comics, Very Funny” appeared on May 29, 1948 in the Saturday Review of Literature. Hardly anybody noticed. Had he lived today, his observations (which these were since the good doctor offered no actual facts, neither about the cases he ever so briefly presented nor for what his conclusions were based on), would have found their way to various social networks, only to be hotly debated among many posters with an opinion to share and no time to do any actual research. But as luck would have it for Wertham, back then there was the next best thing. Reader’s Digest was the publication you wanted to subscribe to if you lived in any of those new dream model homes in the suburbs if you felt you needed some cursory familiarity with current cultural and slightly political topics for the next cocktail party you attended. Rather than requiring you to read articles from newspapers, journals and magazines, honestly who had the time, Reader’s Digest offered you a sampler of carefully curated publications in condensed form. In August 1948, an abbreviated version of his opinion piece made it into the magazine which then was disseminated to several million households. One speech by Hitler’s Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels (who held a doctor of philology degree), actually delivered some months prior to the events on May 10, 1933, was enough to whip the student body of Berlin University into a frenzy. With the war going on, comic books were protected. For one, since they served a purpose, but also because they were popular. But as Stan Lee could have told you, once 1947 turned into 1948, and with his new job title only a few months old, this was no longer the case. Children were buying crime comics in droves and then there were the new romance comics (invented by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby), but the number of new readers was fairly small compared to the readers that were getting out of comic books. Reading comics was no longer the hip thing to do, too closely were they tied to the days of the depression and the war. If you read Superman stories in Action Comics as a child, now as a student in middle school or as a freshman in high school, you felt embarrassed whenever people mentioned them, or worse, when folks recalled having seen you reading such trash. You were almost an adult. Comics, they were for kids.

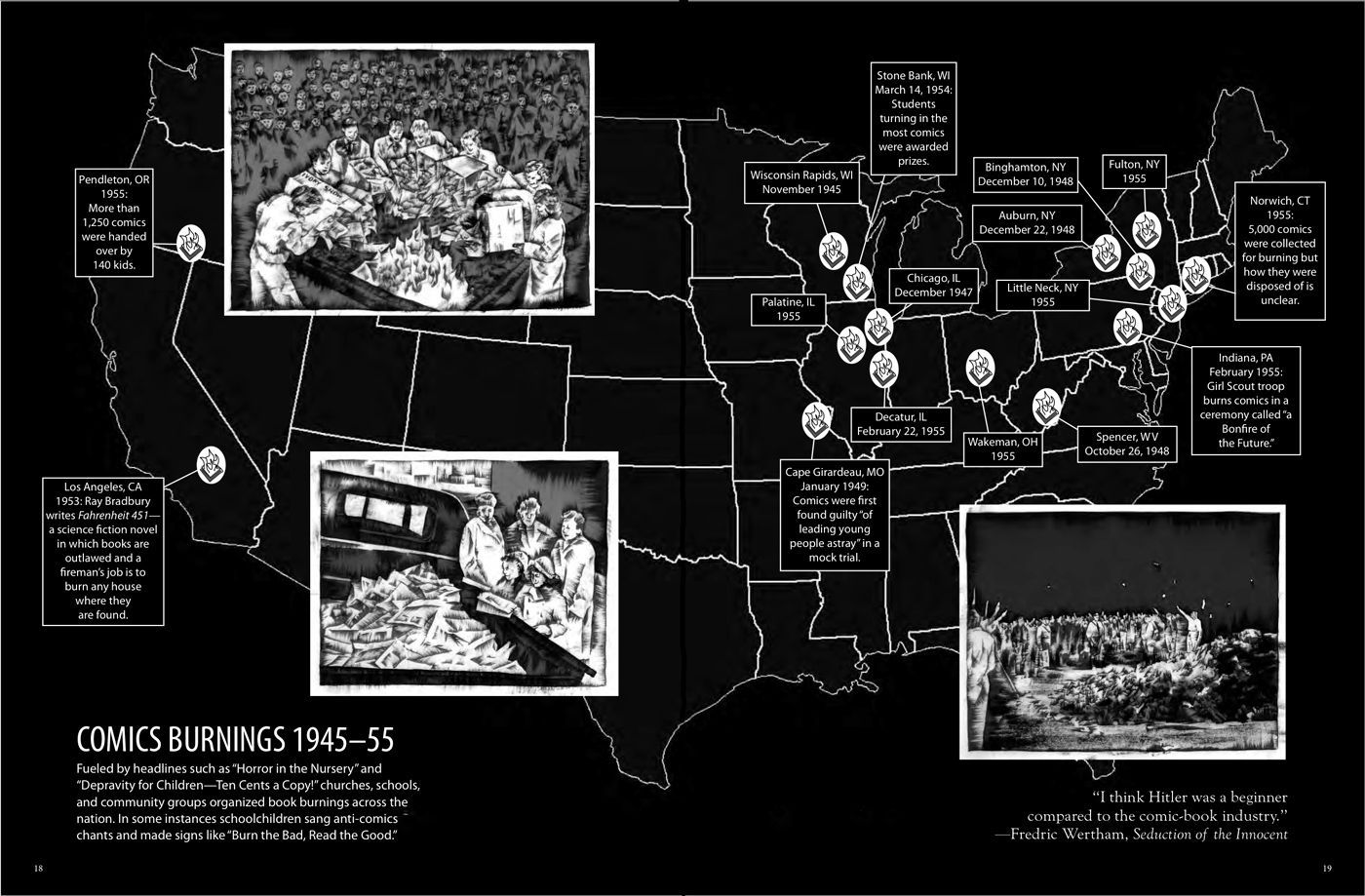

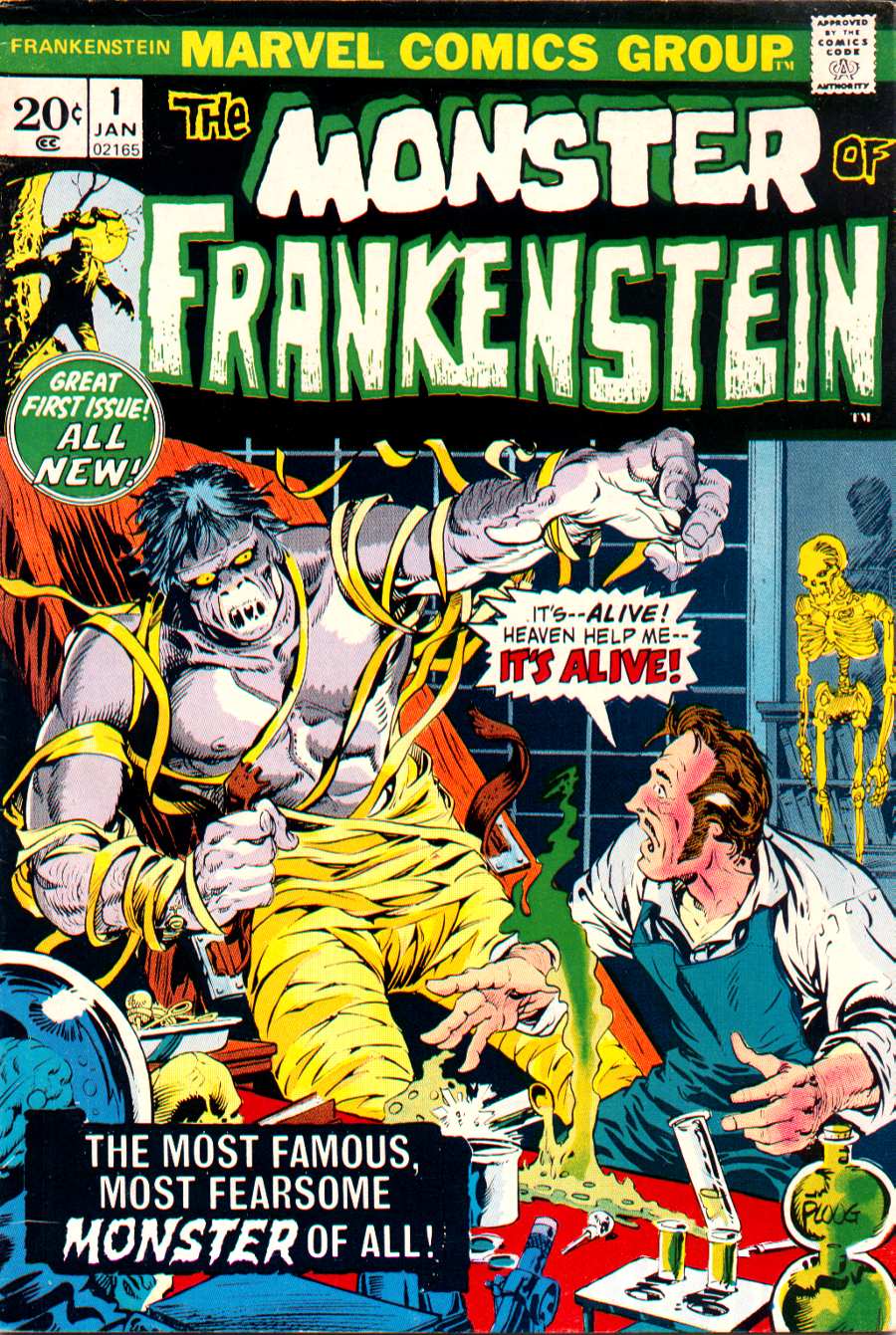

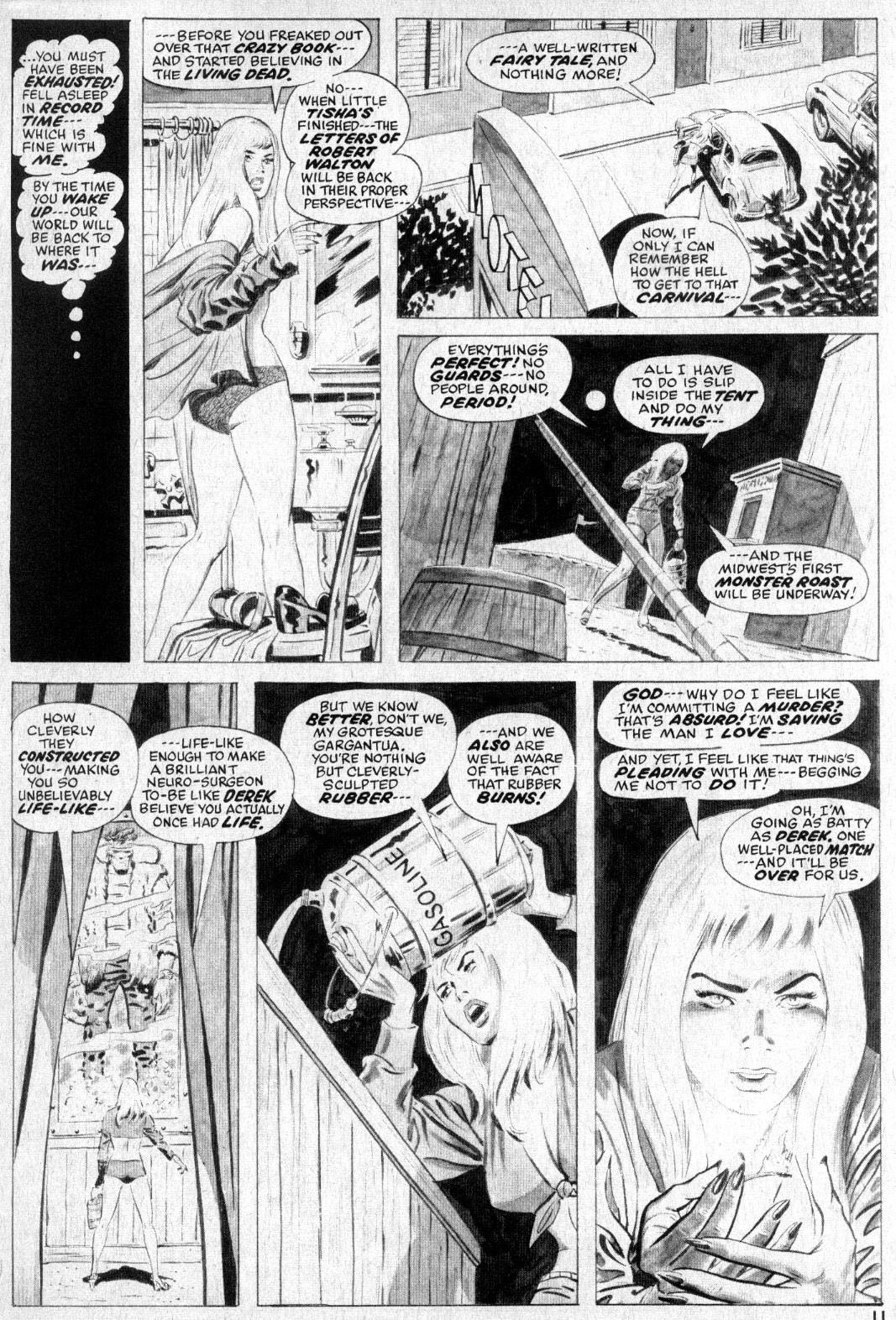

Like the works of H.G. Wells, Thomas Mann and Stefan Zweig and many others, comic books were seen as too dangerous to exist. And this time, no minority report would save them. Nor a small army of once loyal readers who felt no kindship with these pamphlets any longer, and worse, who were now ashamed of them. The first comic book burning took place in Spencer, West Virginia in October 1948. It was just a dress rehearsal for things to come. A few months had passed since Dr. Wertham’s article had made it into the social network that was Reader’s Digest and the telephone lines that connected the new dream houses of suburbia. Women, who had done their share in the war effort when they worked in a factory or some other capacity on the home front, were once again told that a woman’s place was at home and her time was best spent in the kitchen and with raising children, found that their existence in the perfect American middle class was dull as hell once the sheen of the new appliances began to wear off, or they had redecorated their living rooms once too often. But work, that was exclusively for young career girls who were still looking for Mr. Right. You could organize though, in church meetings or parents-teachers associations or similar activities. Like planning events and talking with your girlfriends. And now, many of these mothers had a new reason for concern. Kids, especially boys, they needed to be involved with sports. They needed to develop a healthier body and a spirit of competitiveness if they were to succeed in life. The girls, they shouldn’t get any wrong ideas either. Marriage was not this thing from a fairy tale. There was no prince charming at the end of the story, just some guy who toiled away at some insurance company, bank or ad company in the city, or if you were lucky and you were pretty enough, you stood the chance to land a lawyer or perhaps a doctor. But as with the boys in sports and business, there was a lot competition. A girl had to learn how to make herself presentable. Now this was something, a girl could  learn from her mother or her older sisters, or from a glamour magazine that offered styling advice together with a list of things to do and not to do when it was time for a first date, but most certainly, it was not something you would ever get from a comic. Those books were designed with the wrong kind of ideas in mind. Thus, many of the children and teens, girls and boys, that gathered under the watchful eyes of their parents in Binghamton on December 10, 1948, and ten days later in Auburn, cities located north of New York City, looked prim and proper, almost as if they were cosplaying as miniature editions of their mothers and fathers or they were going with their families to attend church services. The boys had their hair neatly parted, and with their dark suits, their crisp white shirts, their black ties and their overcoats with fur trimming they looked like they were about to sell you insurance coverage for a house or a car. Lo, instead, they’d brought huge carton boxes and brown paper bags. Their contents were now simply old paper, trash that needed taking out. The girls had put on a little makeup for the occasion and they wore gloves with their skirts and dresses and overcoats since this was expected from a young lady. Not all of the kids were middle class, of course, not all of them had parents who could afford to dress their offspring in their image. Some of these teens wore jackets and jeans, the uniform of high schoolers bursting at the seams and looking for trouble. They looked exactly like the kids described in Wertham’s article, and in the magazine columns produced by his ilk, only slightly older. They were the outsiders in this suburban utopia, they looked like they were ready to slash the tires on some Pontiac or Cadillac. It was what you did when you were a rebel without a cause. But not today. Today they wanted to belong. The little children, those who were too small to lift the boxes or too young to be this close to the fires, they watched gleefully. They smiled since they believed that this was expected of them. Whenever the kids looked at their parents, they got nods of encouragement. Burning books was the right thing to do. Though not all of them wanted to burn their comic books, all of them had come to do just that. Partly, because comic books had lost their magic for them, with their once beloved collection untouched in as many months, and partly for reasons that had to do with a sense of duty and peer pressure. Dating had replaced their erstwhile pastime and if not that, other activities had filled the void of spending any time with made-up characters. In any case, they wouldn’t want to be seen with a stack of comics under their arm by a classmate, only in this moment, as they performed this almost religious ritual that marked the end of their childhood, or so they told themselves. When you got older, the toys went into the box and this was where they stayed. It only seemed natural that you’d be called upon to hand your comic books over to the hungry, cleansing fire. Not all of them wanted to do it, like not every student of the student union of Berlin University wanted to throw books and priceless, irreplaceable original manuscripts into the fire in the square outside the opera building, but they did it anyway. The children and the students, they were on the cusp of adulthood, and they looked the part, the boys in their suits with tie, the girls in their pencil skirts, and while the American children looked over their shoulders at their parents with a sense of pride on their soft features, the German kids raised their right arms straight into the air. The kids and the students, they were the good guys. You had to remember that. What was this quote from the Bible, from Matthew? ‘And if thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out, and cast it from thee.” But why stop there? ‘If your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away.” If you didn’t, well, here was Matthew to tell you that there was a nice place in hell reserved for the likes of you. However, those kids in the crowd who did like comic books and the fanciful world they presented, those children with a capacity to pity the giant ape at the end of ‘King Kong”, they knew about body parts. They were a bit too young to understand this intellectually, but still they wondered while some men built and created, why did others have to destroy? In ‘Frankenstein” (1931), Dr. Frankenstein and his hunchback assistant Fritz steal body parts from cemeteries and the laboratory of the nearby university, for Dr. Frankenstein to create life. Though his old mentor Dr. Waldman, who represents the establishment, warns him that no good can come from such a daring endeavor, the young doctor is undeterred, and alas, he succeeds. Unfortunately, for the Creature created from cadavers and given life by its mother electricity, once it’s in the world, Henry Frankenstein has no idea what to do with it. He’s a creator who abandons his work, he even disavows it when it becomes inconvenient as it arrives at an inopportune time. Henry’s getting married to the bland Elizabeth, but he’s already a bad father. It is he who turns a blind eye when Fritz tortures the Creature with a torch in the dungeon where it is chained to a wall. Despite its strength and its size, the Monster instinctively knows that fire is bad, that fire will most likely destroy it. Like the fires in Berlin and New York reduced the works of Thomas Mann, Jerry Siegel and Jack Kirby to ashes. But as a kid, you identified with the Monster, more so for the pathos that actor Boris Karloff brought to what would become his signature role. The Creature was hideous and it had no voice like a little child might not have a voice, a child dragged by its parents to a city square to witness how other kids, older kids set fire to their comic book collection, kids who were taught that if there’s something in the world that you will find offensive, burn it. The Creature has no voice, it can only growl, but it isn’t evil or cruel. This role is reserved for Fritz who sees his place threatened by this late arrival to the Frankenstein household. It is he, the evil big brother, the bully from school, the boy in the jacket and jeans who knows that he and his family are only tolerated in this world of perfectly cut grass and hedges because they are useful for some menial tasks, who likes to torture the weak. But Fritz and the villagers who come for the Monster with their pitchforks, their hunting rifles and their torches, they are also the students who declare the works of writers inferior and offensive to their way of life, their way of thinking, who know that even if they pluck out the eye and cut off the hand, the world will never know their names. Nobody remembers Dr. Waldman the man who dare not leave the beaten path, to look beyond the horizon, to adventure; the script doesn’t even give him a first name. Nobody remembers the cowards and the misinformed. It doesn’t take much to rile up the townsfolk to hunt for the Monster, only a charge of murder that is not proven. But who needs evidence when you are told that the Creature is evil, when you are told that the books of Thomas Mann and Stefan Zweig and many other writers contain dangerous ideas, that comic books cause violence in children? That ideas will make you think about things differently. They all cheer when the Creature is trapped in an abandoned mill, a wood structure that hungrily eats up the flames like a student might eat up the carefully selected words from the Reich Minister of Propaganda. But like when the giant ape fell to his death and the old, dark building with the Monster ends in a fiery holocaust, many of the smaller children did pity the Creature, and some of them saw something more. Those boys who liked how Bruce Cabot looked, the girls who felt a strange sensation as they beheld the unfiltered, raw, uncontrollable sexuality Fay Wray telegraphed with her nubile body, they had no way of knowing that the movie’s director James Whale was one of them, an outsider who had to hide his true identity, lest the men and the women with pitchforks and the torches came for him, the moms who were bored out of their skull who wanted some gossip, some cause and reason to exist, the indifferent fathers who only paid attention when their peace was disturbed, the students who knew they’d only ever be good enough to talk smart but otherwise were not even good enough to shine the boots of the men and the women whose works they threw into the fires their torches had wrought with gleeful abandon. Fifteen years later, across America, the prepubescent girls and boys who felt the first pangs of sexuality rise up in their bodies, they had no inkling that James Whale was a gay man, they didn’t even know what that word meant in this context. What they did know, however, was that they killed the monsters, and that it didn’t take much. If your parents followed an outrage mob this easily without stopping for a moment to think, to form an opinion of their own that was based on merit, you could never ever trust them with the important stuff. Like how you felt inside. If this was how your parents reacted, you had to live a lie, because in their eyes, you’d be the monster if you revealed yourself. The irony would be lost on you for some years to come. The monsters, they had shown themselves on those nights in May and December.

learn from her mother or her older sisters, or from a glamour magazine that offered styling advice together with a list of things to do and not to do when it was time for a first date, but most certainly, it was not something you would ever get from a comic. Those books were designed with the wrong kind of ideas in mind. Thus, many of the children and teens, girls and boys, that gathered under the watchful eyes of their parents in Binghamton on December 10, 1948, and ten days later in Auburn, cities located north of New York City, looked prim and proper, almost as if they were cosplaying as miniature editions of their mothers and fathers or they were going with their families to attend church services. The boys had their hair neatly parted, and with their dark suits, their crisp white shirts, their black ties and their overcoats with fur trimming they looked like they were about to sell you insurance coverage for a house or a car. Lo, instead, they’d brought huge carton boxes and brown paper bags. Their contents were now simply old paper, trash that needed taking out. The girls had put on a little makeup for the occasion and they wore gloves with their skirts and dresses and overcoats since this was expected from a young lady. Not all of the kids were middle class, of course, not all of them had parents who could afford to dress their offspring in their image. Some of these teens wore jackets and jeans, the uniform of high schoolers bursting at the seams and looking for trouble. They looked exactly like the kids described in Wertham’s article, and in the magazine columns produced by his ilk, only slightly older. They were the outsiders in this suburban utopia, they looked like they were ready to slash the tires on some Pontiac or Cadillac. It was what you did when you were a rebel without a cause. But not today. Today they wanted to belong. The little children, those who were too small to lift the boxes or too young to be this close to the fires, they watched gleefully. They smiled since they believed that this was expected of them. Whenever the kids looked at their parents, they got nods of encouragement. Burning books was the right thing to do. Though not all of them wanted to burn their comic books, all of them had come to do just that. Partly, because comic books had lost their magic for them, with their once beloved collection untouched in as many months, and partly for reasons that had to do with a sense of duty and peer pressure. Dating had replaced their erstwhile pastime and if not that, other activities had filled the void of spending any time with made-up characters. In any case, they wouldn’t want to be seen with a stack of comics under their arm by a classmate, only in this moment, as they performed this almost religious ritual that marked the end of their childhood, or so they told themselves. When you got older, the toys went into the box and this was where they stayed. It only seemed natural that you’d be called upon to hand your comic books over to the hungry, cleansing fire. Not all of them wanted to do it, like not every student of the student union of Berlin University wanted to throw books and priceless, irreplaceable original manuscripts into the fire in the square outside the opera building, but they did it anyway. The children and the students, they were on the cusp of adulthood, and they looked the part, the boys in their suits with tie, the girls in their pencil skirts, and while the American children looked over their shoulders at their parents with a sense of pride on their soft features, the German kids raised their right arms straight into the air. The kids and the students, they were the good guys. You had to remember that. What was this quote from the Bible, from Matthew? ‘And if thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out, and cast it from thee.” But why stop there? ‘If your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away.” If you didn’t, well, here was Matthew to tell you that there was a nice place in hell reserved for the likes of you. However, those kids in the crowd who did like comic books and the fanciful world they presented, those children with a capacity to pity the giant ape at the end of ‘King Kong”, they knew about body parts. They were a bit too young to understand this intellectually, but still they wondered while some men built and created, why did others have to destroy? In ‘Frankenstein” (1931), Dr. Frankenstein and his hunchback assistant Fritz steal body parts from cemeteries and the laboratory of the nearby university, for Dr. Frankenstein to create life. Though his old mentor Dr. Waldman, who represents the establishment, warns him that no good can come from such a daring endeavor, the young doctor is undeterred, and alas, he succeeds. Unfortunately, for the Creature created from cadavers and given life by its mother electricity, once it’s in the world, Henry Frankenstein has no idea what to do with it. He’s a creator who abandons his work, he even disavows it when it becomes inconvenient as it arrives at an inopportune time. Henry’s getting married to the bland Elizabeth, but he’s already a bad father. It is he who turns a blind eye when Fritz tortures the Creature with a torch in the dungeon where it is chained to a wall. Despite its strength and its size, the Monster instinctively knows that fire is bad, that fire will most likely destroy it. Like the fires in Berlin and New York reduced the works of Thomas Mann, Jerry Siegel and Jack Kirby to ashes. But as a kid, you identified with the Monster, more so for the pathos that actor Boris Karloff brought to what would become his signature role. The Creature was hideous and it had no voice like a little child might not have a voice, a child dragged by its parents to a city square to witness how other kids, older kids set fire to their comic book collection, kids who were taught that if there’s something in the world that you will find offensive, burn it. The Creature has no voice, it can only growl, but it isn’t evil or cruel. This role is reserved for Fritz who sees his place threatened by this late arrival to the Frankenstein household. It is he, the evil big brother, the bully from school, the boy in the jacket and jeans who knows that he and his family are only tolerated in this world of perfectly cut grass and hedges because they are useful for some menial tasks, who likes to torture the weak. But Fritz and the villagers who come for the Monster with their pitchforks, their hunting rifles and their torches, they are also the students who declare the works of writers inferior and offensive to their way of life, their way of thinking, who know that even if they pluck out the eye and cut off the hand, the world will never know their names. Nobody remembers Dr. Waldman the man who dare not leave the beaten path, to look beyond the horizon, to adventure; the script doesn’t even give him a first name. Nobody remembers the cowards and the misinformed. It doesn’t take much to rile up the townsfolk to hunt for the Monster, only a charge of murder that is not proven. But who needs evidence when you are told that the Creature is evil, when you are told that the books of Thomas Mann and Stefan Zweig and many other writers contain dangerous ideas, that comic books cause violence in children? That ideas will make you think about things differently. They all cheer when the Creature is trapped in an abandoned mill, a wood structure that hungrily eats up the flames like a student might eat up the carefully selected words from the Reich Minister of Propaganda. But like when the giant ape fell to his death and the old, dark building with the Monster ends in a fiery holocaust, many of the smaller children did pity the Creature, and some of them saw something more. Those boys who liked how Bruce Cabot looked, the girls who felt a strange sensation as they beheld the unfiltered, raw, uncontrollable sexuality Fay Wray telegraphed with her nubile body, they had no way of knowing that the movie’s director James Whale was one of them, an outsider who had to hide his true identity, lest the men and the women with pitchforks and the torches came for him, the moms who were bored out of their skull who wanted some gossip, some cause and reason to exist, the indifferent fathers who only paid attention when their peace was disturbed, the students who knew they’d only ever be good enough to talk smart but otherwise were not even good enough to shine the boots of the men and the women whose works they threw into the fires their torches had wrought with gleeful abandon. Fifteen years later, across America, the prepubescent girls and boys who felt the first pangs of sexuality rise up in their bodies, they had no inkling that James Whale was a gay man, they didn’t even know what that word meant in this context. What they did know, however, was that they killed the monsters, and that it didn’t take much. If your parents followed an outrage mob this easily without stopping for a moment to think, to form an opinion of their own that was based on merit, you could never ever trust them with the important stuff. Like how you felt inside. If this was how your parents reacted, you had to live a lie, because in their eyes, you’d be the monster if you revealed yourself. The irony would be lost on you for some years to come. The monsters, they had shown themselves on those nights in May and December.

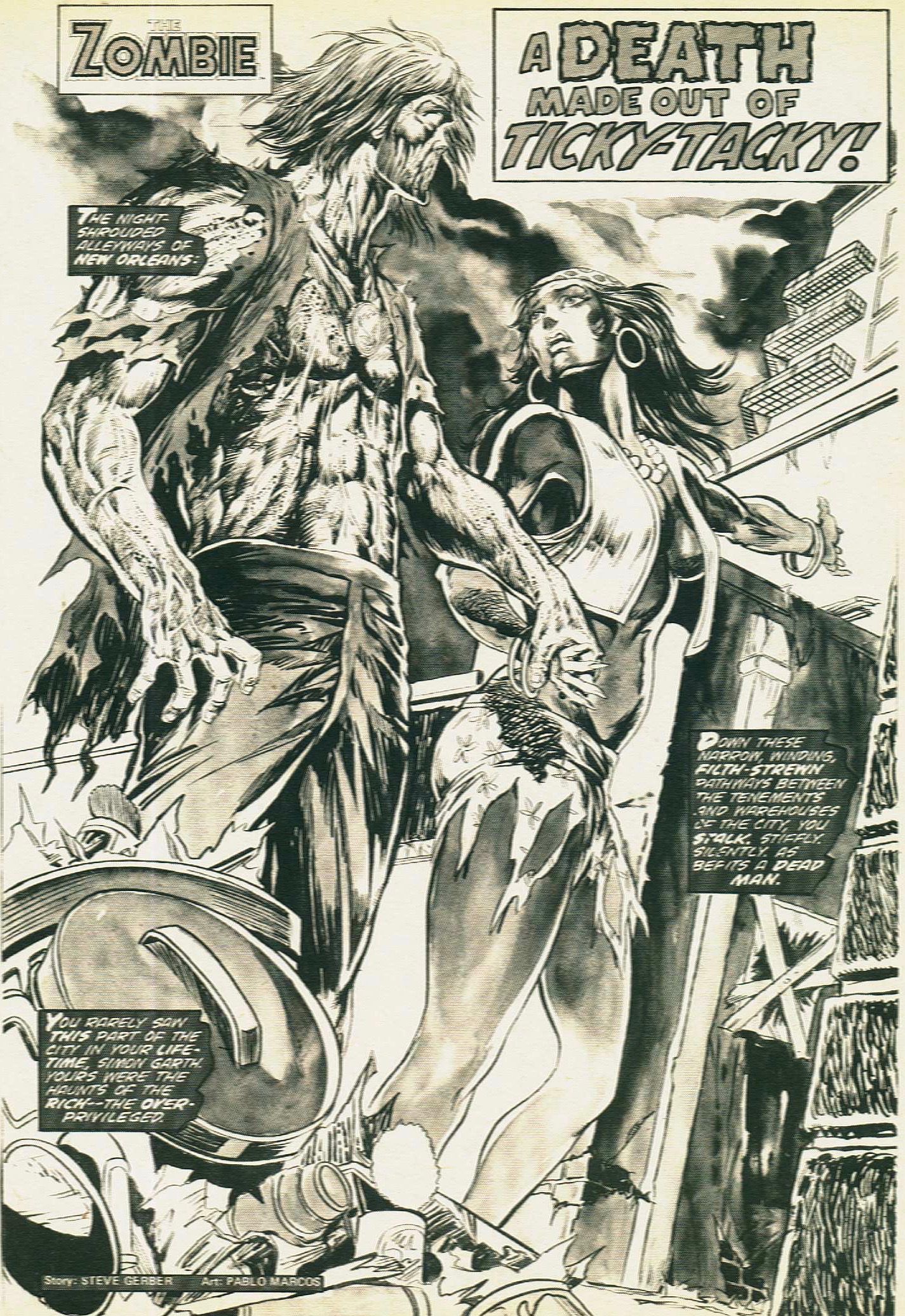

Like the book burnings organized by the student union in Berlin in 1933, the comic book burnings moved from one city to the next. Whereas some of the dates in Nazi Germany had to be postponed since there was heavy rain on that day, perhaps God wept for the books that were lost, not so much luck in America a decade and a half later. Maybe God didn’t care much for comic books either. As the drive to destroy what better men and women had created moved down South, as it inevitably had to do, early in 1949, they came for the children in Jackson, Missouri. Well, they came for their comic books, and like before, either because the kids had outgrown them or they were shamed into telling themselves that, dutifully they handed them over to the grownups who knew best or carried the cardboard boxes themselves to the place designated for the public burning. Most of children did it voluntarily, one boy did it reluctantly, but he knew he had to. His parents had told him that they had to think about the neighbors, what they might think. Even to a boy who’d turned just eight a few months earlier, this didn’t make much sense. If everybody wondered what their neighbors thought, then nobody acted of their own free will. To him it felt like some weird power had taken over the minds of his parents and the folks who lived next door. But then, the boy was also a bit of a dreamer and people told him that he had an imagination that was too vivid for his own good, that his head was up in the clouds too often. No wonder stronger kids picked on him he was being told. The kids could sniff a sissy from a mile away, only that it didn’t take much to make him cry or to beat him up. He was small and frail, and he had thin blonde hair and he wore glasses. That he wore crisp white shirt to class only put another target on his back, especially with the boys who wore leather jackets and jeans and who were older, old enough to smoke. They made fun of him, which was alright with the other kids, kids who teased him about his comic books. His latest purchases, comics he had not read yet, he hid those under the floorboards in his room. Even though he liked to visit places he could only go to when he looked at those four-colored pages and in his mind, or whenever he picked up some of those old pulp books that allowed him to dream of himself as a strong barbarian who knew how to wield a sword and who possessed the cunning he needed to stay alive in a world that came with sorcerers and beautiful, barely clad girls, he still had the wherewithal to know that some treasures best stayed far away from the prying eyes of people who were less astute than he was, including his parents. To the grownups and some of those older children, these books might well have been porn, contraband or worse, to him these were messages from alien worlds. Thus, when his parents asked him to bring his beloved comic book collection to give it over to the flames that rose into the evening sky of Jackson, he did as he was asked. Since he was so small in stature and so frail, his father walked up to the blaze while the boy expressed a solemn demeanor on his face as if to mark the momentous occasion like an officer might commemorate a fallen brother in arms. His newest acquisitions and the old pulps magazines with their adventure tales of the barbarian with the sword, the beautiful girls and the wizards, they were all safe in their secret hiding place in his room. But indeed, among the cheers from some of the other kids, those kids who looked like miniature version of their mothers and fathers and the bullies who beat him up, something had died. Only they didn’t realize it. He stepped forward and then he stood right next to his father as he watched the cheap newsprint paper curl up at the edges while the four-colored worlds these pages held turned charcoal black. He and his dad watched in silence as a chunk of his comic book collection turned to black and gray ash like this was something perfectly normal, something fathers and sons could bond over. But when his dad looked over his shoulder to nod at the boy’s mother and their neighbors to emphasize that there was nothing deviant going on in their household, that they were like any other family, the boy crouched down. He’d noticed that whenever the older kids turned their boxes upside down near the fire, sometimes a book would slip to one side. In fact, from his position he could see two comic books that were in near perfect condition, as perfect as you might expect from well-read books, and they were close enough for him to grab them. This was what he did, and he hid them under his coat like newly hatched birds that had fallen out of the nest. Best of all, he hadn’t read those books. On May 10, 1934, exactly one year after the rallies of the students in Germany, writers who’d fled their home country to live in exile, in France first and later in the United States, established the Library of the Burned Books to collect the works that had been banned or destroyed or censored. Theirs wouldn’t be the last museum for persecuted arts, but sadly just the first. However, nobody would collect the works that were lost in Binghamton, in Auburn or in Jackson or in any other city in America. No museum would display a splash page by Jack Kirby the artist whose cover for Captain America Comics No. 1 showed the star-spangled hero as he punched Adolf Hitler in the face nine months before America entered into the war. Instead there’d come a time when artists like Roy Lichtenstein co-opted the works of Tony Abruzzo and Irv Novick among others to create the pop art paintings that made the new intellectual elite swoon who’d never and would never touch a comic book in their life. Lichtenstein wasn’t without his fair share of loud distractors, but he was well-versed in the art of mudding the waters to make them seem deep. To answers his critics, art critics, he promulgated that his works were ‘critically transformed”, though it took decades before any actual comic book artists would call him out. When they did, it stung. Maybe Dave Gibbons put it best when he said: ‘I am not convinced that it is art.” Gibbons is of course one of the creators of Watchmen, the only comic book to make it on the list of the 100 Best Novels published in the English language where it sits next to the works of Vladimir Nabokov and J.D. Salinger, works that at one point or another were expunged from high school libraries, even outlawed. In 2014, Russ Heath, a legend in his own right, drew a short comic strip to express his emotions of having his art appropriate by the likes of Lichtenstein when Russ was a struggling comic book artist trying to put food on the table for his family. Heath also created the strip to say his thanks to the Hero Initiative, an organization that helps to connect those in the comic industry with medical aid, something which is especially pertinent for older creators, the very same men and woman whose books were met with so little regard or which were thought so dangerous that they needed to be destroyed in the fire. Then there’s the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, ‘a non-profit organization dedicated to protecting the First Amendment rights of the comics medium.”, a right that safeguards free speech, the press, and allows any citizen to petition the government. But how, as an artist or book comic fan, do you redress your grievances when it’s the good guys who set fire to comic books or any book for that matter? How do you take up your argument with an artist who is surrounded by an intellectual elite who passes judgment on what is important art? Harry Donenfeld, the man who bought Superman, had a life-size painting made of the character which hung over his desk, a desk the hero’s creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster often had to walk past while they were allowed to work as hired hands on the Superman books that were widely popular and which did major bank for Donenfeld. Hugh Joseph Ward, the artist commissioned by Donenfeld, a man who’d painted many lurid covers for the latter’s pulp magazine, he was paid more for this single piece of work than Siegel and Shuster were for the rights to the superhero character. In early 1949, none of this was on the mind of the frail, bespectacled boy when he walked away from the fire next to his parents who for that one moment in time seemed to be proud of him. Not because their son had grabbed a copy of Space Busters and Wild Boy of the Congo when nobody else was looking, not because they could already sense that one day the establishment of the city, Jackson, Missouri, would be honoring his ‘prolific pop culture contributions”, and that one of the creators of two generations later would say about the boy: ‘He is a legend we still look to for guidance and inspiration.” They couldn’t know it yet and he couldn’t know it yet but when he spoke to mark the occasion of being bestowed with the honors of his city, he’d speak to a crowd of people in the Montgomery Bank Conference and Training Center with no space left in the huge conference hall. No, his parents were proud of him because for what they knew. He’d done good. He’d not embarrassed them in front of their friends and neighbors. He had handed over his books without any protest. Maybe there was hope that he’d turn out half-decent after all. As he walked next to his parents, the boy knew this, but as felt the weight of those two comic books he’d swiped from the flames secretly pressing against his underdeveloped chest and he heard the faint rustle of the pages as if they were fallen leaves you heard in the backyard on a night in winter that comes before a new spring, he also knew that like the monsters, wherever he’d walk, he’d walk alone. Only over time, he’d be able to connect with like-minded kids, not from his school, though there’d come a moment in time when his beloved comic books saw a meteoric rise in popularity the likes not witnessed prior, or in fact with any kid in Jackson, but with readers like Jerry Bails from Kansas City with whom he’d exchange hundreds of letters before they created the first organized fandom movement the industry together. But all of that was far away in the future. On this late evening however, he realized that among the good guys, he was the boy who’d done his part to save the Monster from the blazing mill. The boy’s name was Roy Thomas.

Since he was so small in stature and so frail, his father walked up to the blaze while the boy expressed a solemn demeanor on his face as if to mark the momentous occasion like an officer might commemorate a fallen brother in arms. His newest acquisitions and the old pulps magazines with their adventure tales of the barbarian with the sword, the beautiful girls and the wizards, they were all safe in their secret hiding place in his room. But indeed, among the cheers from some of the other kids, those kids who looked like miniature version of their mothers and fathers and the bullies who beat him up, something had died. Only they didn’t realize it. He stepped forward and then he stood right next to his father as he watched the cheap newsprint paper curl up at the edges while the four-colored worlds these pages held turned charcoal black. He and his dad watched in silence as a chunk of his comic book collection turned to black and gray ash like this was something perfectly normal, something fathers and sons could bond over. But when his dad looked over his shoulder to nod at the boy’s mother and their neighbors to emphasize that there was nothing deviant going on in their household, that they were like any other family, the boy crouched down. He’d noticed that whenever the older kids turned their boxes upside down near the fire, sometimes a book would slip to one side. In fact, from his position he could see two comic books that were in near perfect condition, as perfect as you might expect from well-read books, and they were close enough for him to grab them. This was what he did, and he hid them under his coat like newly hatched birds that had fallen out of the nest. Best of all, he hadn’t read those books. On May 10, 1934, exactly one year after the rallies of the students in Germany, writers who’d fled their home country to live in exile, in France first and later in the United States, established the Library of the Burned Books to collect the works that had been banned or destroyed or censored. Theirs wouldn’t be the last museum for persecuted arts, but sadly just the first. However, nobody would collect the works that were lost in Binghamton, in Auburn or in Jackson or in any other city in America. No museum would display a splash page by Jack Kirby the artist whose cover for Captain America Comics No. 1 showed the star-spangled hero as he punched Adolf Hitler in the face nine months before America entered into the war. Instead there’d come a time when artists like Roy Lichtenstein co-opted the works of Tony Abruzzo and Irv Novick among others to create the pop art paintings that made the new intellectual elite swoon who’d never and would never touch a comic book in their life. Lichtenstein wasn’t without his fair share of loud distractors, but he was well-versed in the art of mudding the waters to make them seem deep. To answers his critics, art critics, he promulgated that his works were ‘critically transformed”, though it took decades before any actual comic book artists would call him out. When they did, it stung. Maybe Dave Gibbons put it best when he said: ‘I am not convinced that it is art.” Gibbons is of course one of the creators of Watchmen, the only comic book to make it on the list of the 100 Best Novels published in the English language where it sits next to the works of Vladimir Nabokov and J.D. Salinger, works that at one point or another were expunged from high school libraries, even outlawed. In 2014, Russ Heath, a legend in his own right, drew a short comic strip to express his emotions of having his art appropriate by the likes of Lichtenstein when Russ was a struggling comic book artist trying to put food on the table for his family. Heath also created the strip to say his thanks to the Hero Initiative, an organization that helps to connect those in the comic industry with medical aid, something which is especially pertinent for older creators, the very same men and woman whose books were met with so little regard or which were thought so dangerous that they needed to be destroyed in the fire. Then there’s the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, ‘a non-profit organization dedicated to protecting the First Amendment rights of the comics medium.”, a right that safeguards free speech, the press, and allows any citizen to petition the government. But how, as an artist or book comic fan, do you redress your grievances when it’s the good guys who set fire to comic books or any book for that matter? How do you take up your argument with an artist who is surrounded by an intellectual elite who passes judgment on what is important art? Harry Donenfeld, the man who bought Superman, had a life-size painting made of the character which hung over his desk, a desk the hero’s creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster often had to walk past while they were allowed to work as hired hands on the Superman books that were widely popular and which did major bank for Donenfeld. Hugh Joseph Ward, the artist commissioned by Donenfeld, a man who’d painted many lurid covers for the latter’s pulp magazine, he was paid more for this single piece of work than Siegel and Shuster were for the rights to the superhero character. In early 1949, none of this was on the mind of the frail, bespectacled boy when he walked away from the fire next to his parents who for that one moment in time seemed to be proud of him. Not because their son had grabbed a copy of Space Busters and Wild Boy of the Congo when nobody else was looking, not because they could already sense that one day the establishment of the city, Jackson, Missouri, would be honoring his ‘prolific pop culture contributions”, and that one of the creators of two generations later would say about the boy: ‘He is a legend we still look to for guidance and inspiration.” They couldn’t know it yet and he couldn’t know it yet but when he spoke to mark the occasion of being bestowed with the honors of his city, he’d speak to a crowd of people in the Montgomery Bank Conference and Training Center with no space left in the huge conference hall. No, his parents were proud of him because for what they knew. He’d done good. He’d not embarrassed them in front of their friends and neighbors. He had handed over his books without any protest. Maybe there was hope that he’d turn out half-decent after all. As he walked next to his parents, the boy knew this, but as felt the weight of those two comic books he’d swiped from the flames secretly pressing against his underdeveloped chest and he heard the faint rustle of the pages as if they were fallen leaves you heard in the backyard on a night in winter that comes before a new spring, he also knew that like the monsters, wherever he’d walk, he’d walk alone. Only over time, he’d be able to connect with like-minded kids, not from his school, though there’d come a moment in time when his beloved comic books saw a meteoric rise in popularity the likes not witnessed prior, or in fact with any kid in Jackson, but with readers like Jerry Bails from Kansas City with whom he’d exchange hundreds of letters before they created the first organized fandom movement the industry together. But all of that was far away in the future. On this late evening however, he realized that among the good guys, he was the boy who’d done his part to save the Monster from the blazing mill. The boy’s name was Roy Thomas.